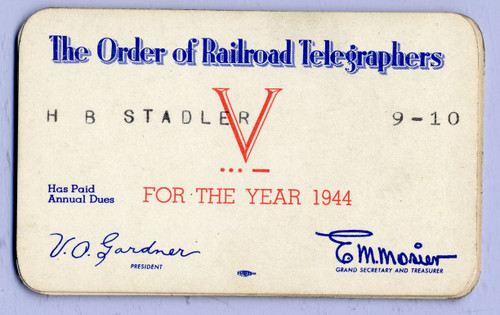

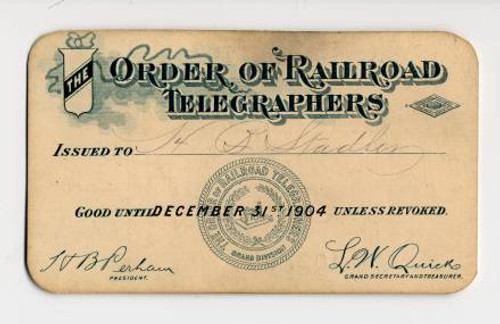

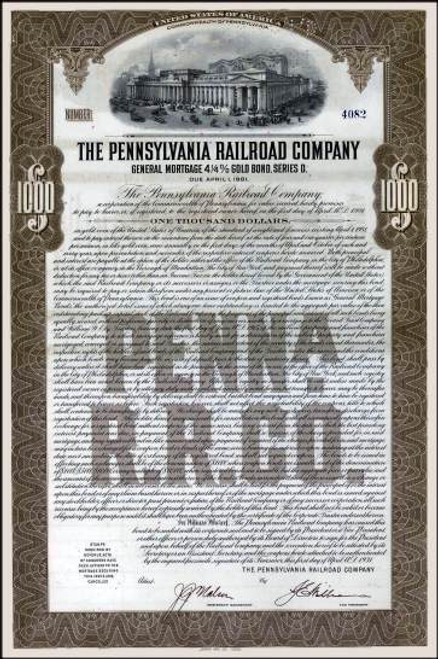

Order of Railroad Telegraphers Membership Card - Stamped V for Victory during WWII - 1945 The Order of Railroad Telegraphers (ORT) was a United States labor union established in the late nineteenth century to promote the interests of telegraph operators working for the railroads. Long working hours were a major issue among railroad telegraphers. Railroad operators were the "air traffic controllers" of the railroads; long hours and the resulting fatigue could result in errors in judgment and serious accidents. In 1907, a bill was introduced in Congress to limit the maximum number of hours that railroad employees had to work in a twenty-four hour period, known as the La Follette Hours of Service Act, after its chief sponsor, Senator Robert La Follette Sr. of Wisconsin. While this bill did not specifically address railroad telegraphers, a similar bill had been introduced and passed in the House of Representatives to limit the working hours of railroad telegraphers to no more than nine hours in a 24-hour period. This bill was offered as an amendment to the La Follette bill in the Senate; however, members of the committee to which it was referred bowed to pressure from the railroads and attempted to increase the maximum number of working hours allowed in a single day to twelve hours, a move which enraged ORT members. They immediately began using the telegraph to bombard their congressional representatives with messages of protest, which resulted in the original nine-hour limit being reinstated. The La Follette Hours of Service Act was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt on March 4, 1907. Although the passage of the Hours of Service Act improved conditions for railroad operators, operators at small stations might still be required to remain "on duty" for as much as twelve hours in a day, or have their total working hours spread over a longer interval, known as a "split trick." The ORT supported an amendment to reduce the workday still further to eight hours and eliminate the split trick. However, the ORT did not coordinate its efforts with the other railroad unions, and when the Adamson Act, passed in 1917, mandated an eight-hour working day for most railroad employees, it did not explicitly include telegraphers.:316 With the entry of the U.S. into the first World War, the railroad and telegraph industries were placed under government control. On December 26, 1917, the United States Railroad Administration (USRA) took control of the railroads.[12] The USRA was generally supportive of the interests of the union members; during the period of nationalization, railroad operators were limited to an eight-hour workday and the ORT was granted collective bargaining capability on a national level. The ORT was able to sign agreements with the Santa Fe, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad, the Reading Railroad, and the Pennsylvania Railroad. By 1917, ORT membership had grown to 46,000. A Board of Railroad Wages and Working Conditions was set up by the Railroad Administration. ORT Grand Chief Perham appeared before the Board to request a 40 percent increase in pay, an eight-hour day, and relief from handling government mail by railroad telegraphers. While the Board did provide minimal wage increases, they were far less than the requested 40 percent, and the resulting discontent among ORT members resulted in Perham's defeat in a 1919 election and his replacement as Grand Chief by E. J. Manion. Federal control of the railroads ended on March 1, 1920. When the contracts that had been negotiated while under federal control expired the following year, the ORT had to re-negotiate agreements with the individual railroads. The early 1920s were the peak years for ORT membership; by 1922, the union boasted 78,000 members in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. Some railroads, including the Santa Fe, the Louisville and Nashville, and the Great Northern, maintained essentially the same agreements with the ORT that they had established during the years of government control. A dispute with the Atlantic Coast Line led to a strike in 1925 that ended with the railroad making concessions to the union and signing a new agreement. Membership in the ORT began to decline after the stock market crash of 1929, due not only to economic conditions but also to the increasing use of centralized traffic control, which no longer required the presence of a telegrapher in each station. The membership fell to 63,000 in 1929, and continued to fall throughout the Depression years of the 1930s. As a result of the declining membership and the loss of revenue from dues, the ORT was forced to suspend payment of pensions to retired members through the mutual benefit program. By the beginning of World War II, ORT membership had fallen to around 40,000 as the railroads became involved in the war effort. Railroad telegraphers often had multiple employment as station agents, express agents, and Western Union telegraphers, with each employer paying a portion of the operators' salary. In 1930, the Railway Express Agency, which employed some ORT members as express agents, began handling shipments of perishable items, which had previously been handled as freight shipments on the Seaboard Air Line Railroad. The ORT members who served as express agents as well as telegraphers for the railroad were offered individual pay adjustments on short notice, which the ORT claimed was a violation of the Railway Labor Act of 1926, which required 30 days' notice of any pay adjustment. Additionally, the ORT charged that the individual pay adjustments were in violation of a collective bargaining agreement that had been signed with Railway Express in 1917. When the company refused to participate in a Board of Adjustment, a suit was brought by the ORT in U.S. District Court. The court's decision in favor of the ORT was reversed by the Circuit Court of Appeals, and the suit was finally brought to the U.S. Supreme Court, which decided in favor of the union in 1944. The Supreme Court decision established the primacy of agreements reached by collective bargaining over individual agreements, and upheld the union's right to engage in collective bargaining on behalf of its members. The decline of the railroad industry in the 1950s and 1960s led to layoffs and discharges of ORT members. When the ORT attempted to protect its members' jobs by demanding the right to veto job cutbacks, it was accused of "featherbedding," requiring the employment of unnecessary workers, by railroad executives. The ORT called a strike in 1962 to protest layoffs of 600 telegraphers on the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad. A mediation board created by President John F. Kennedy found in favor of the railroad in October 1962, calling the layoffs justified and denying the union the right to veto layoffs. However, the railroad was required to give 90 days' notice to terminated employees, and to pay laid-off telegraphers 60 percent of their annual salary for as much as five years. In 1965, the ORT changed its name to the Transportation Communications Employees Union; that union was merged into the Brotherhood of Railway & Airline Clerks, Freight Handlers, Express & Station Employes (BRAC) in 1969. At the time of the merger, the ORT had about 30,000 members. In 1985, BRAC chose to revive the TCU identity, and in July 2005, the "new" TCU affiliated with the International Association of Machinists, with full merger to occur no later than January 2012 History from Wikipedia and OldCompany.com.

Order of Railroad Telegraphers Membership Card ("Air traffic controllers" of the railroads) - Stamped V for Victory during WWII - 1944

MSRP:

$39.95

$29.95

(You save

$10.00

)

- SKU:

- newitem334872622

- Gift wrapping:

- Options available in Checkout