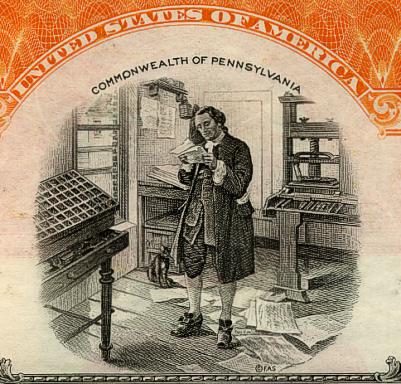

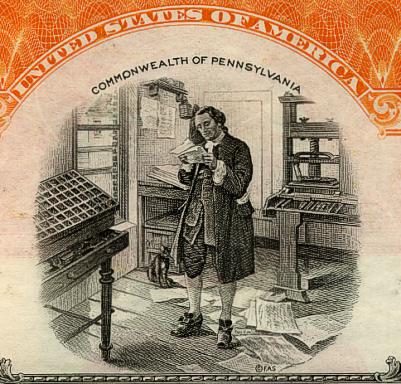

Beautiful engraved RARE specimen certificate from the Curtis-Martin Newspapers dated in 1930. This historic document was printed by Security Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of Benjamin Franklin in his printing office. This item is over 77 years old. 20 coupons attached on right side. Rare, possibly unique.

Certificate Vignette Cyrus Curtis was a significant U.S. publisher. He was born in Portland, Maine and entered the publishing business there with a weekly newspaper. He founded the Philadlephia based Curtis Publishing Company, which published the Ladies Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post, which was known for the numerous covers by Norman Rockwell. He was doing business under the name of Curtis-Martin Newspaper, Inc. Curtis-Martin Newspapers and Cyrus Curtis purchased the Philadelphia Inquirier in 1930. This bond helped finance that purchase. The Philadelphia Inquirer was founded as The Pennsylvania Inquirer by printer John R. Walker and John Norvell, former editor of Philadelphia's largest newspaper the Aurora & Gazette. In an editorial, the first issue of The Pennsylvania Inquirer promised that the paper would be devoted to the right of a minority to voice their opinion and "the maintenance of the rights and liberties of the people, equally against the abuses as the usurpation of power." They pledged support to then President Andrew Jackson and "home industries, American manufactures, and internal improvements that so materially contribute to the agricultural, commercial and national prosperity".[2] Founded on June 1, 1829, The Philadelphia Inquirer is the third oldest surviving daily newspaper in the United States. However, in 1962, an Inquirer-commissioned historian traced The Inquirer to John Dunlap's The Pennsylvania Packet, which was founded on October 28, 1771. In 1850 The Packet was merged with another newspaper The North American, which later merged with the Philadelphia Public Ledger. Finally, the Public Ledger merged with The Philadelphia Inquirer in the 1930s and between 1962 and 1975, a line on The Inquirer's front page claimed that the newspaper is the United States' oldest surviving daily newspaper. Six months after The Inquirer was founded, with competition from eight established daily newspapers, lack of funds forced Norvell and Walker to sell the newspaper to publisher and United States Gazette associate editor Jesper Harding. After Harding acquired The Pennsylvania Inquirer, it was briefly published as an afternoon paper before returning to its original morning format in January 1830. Under Harding, in 1829, The Inquirer moved from its original location between Front and Second streets to between Second and Third streets. When Harding bought and merged the Morning Journal in January 1830, the newspaper was moved to South Second Street. Ten years later The Inquirer again was moved, this time to its own building at the corner of Third Street and Carter's Alley. Harding expanded The Inquirer's content and the paper soon grew into a major Philadelphian newspaper. The expanded content included the addition of fiction, and in 1840, Harding gained rights to publish several Charles Dickens novels for which Dickens' was paid a significant amount. At the time the common practice was to pay little or nothing for the rights of foreign authors' works. Harding retired in 1859 and was succeeded by his son William White Harding, who had become a partner three years earlier. William Harding changed the name of the newspaper to its current name, The Philadelphia Inquirer. Harding, in an attempt to increase circulation, cut the price of the paper, began delivery routes and had newsboys selling the paper on the street. In 1859 circulation had been around 7,000 and by 1863 it had increased to 70,000. Part of the increase was due to the interest in news during the American Civil War. 25,000 to 30,000 copies of The Inquirer were often distributed to Union soldiers during the war and several times the U.S. government asked The Philadelphia Inquirer to issue a special edition specifically for soldiers. The Philadelphia Inquirer supported the Union, but Harding wanted their coverage to remain neutral. Confederate generals often sought copies of the paper, believing that the newspaper's war coverage was accurate. Inquirer journalist Uriah Hunt Painter was at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861, a battle which ended in a Confederate victory. Initial reports from the government claimed a Union victory, but The Inquirer went with Painter's firsthand account. Crowds threatened to burn The Inquirer's building down because of the report. Another report, this time about General George Meade, angered Meade enough he punished Edward Crapsey, the reporter who wrote it. Crapsey and other war correspondents later decided to attribute any victories of the Army of the Potomac, Meade's command, to Ulysses S. Grant commander of the entire Union army. Any defeats by the Army of the Potomac would be attributed to Meade. During the war, The Inquirer continued to grow with more staff being added and another move into a larger building on Chestnut Street. However, after the war, economic hits combined with Harding becoming ill, hurt The Inquirer. Despite Philadelphia's population growth, distribution fell from 70,000 during the Civil War to 5,000 in 1888. Beginning in 1889, the paper was sold to James Elverson. To bring back the paper, Elverson moved The Inquirer to a new building with the latest printing technology and an increased staff. The "new" Philadelphia Inquirer premiered on March 1 and was successful enough that Elverson started a Sunday edition of the paper. In 1890, in an attempt to increase circulation further, the price of The Inquirer was cut and the paper's size was increased, mostly with classified advertisements. After five years The Inquirer had to move into a larger building on Market Street and later expanded into adjacent property. After Elverson's death in 1911, his son James Elverson Jr. took charge. Under Elverson Jr., the newspaper continued to grow, eventually needing to move again. Elverson Jr. bought land at Broad and Callowhill Streets and built the eighteen story Elverson Building, now known as the Inquirer-Daily News Building. The first Inquirer issue printed at the building came out on July 13, 1925. Elverson Jr. died a few years later in 1929 and his sister, Eleanor Elverson Patenotre, took over. Patenotre ordered cuts throughout the paper, but was not really interested in managing The Inquirer and ownership was soon put up for sale. Cyrus Curtis and Curtis-Martin Newspapers Inc. bought the newspaper on March 5, 1930. Curtis died a year later and his son-in-law, John Martin, took charge. Martin merged The Inquirer with another paper, the Philadelphia Public Ledger, but the Great Depression hurt Curtis-Martin Newspapers and the company defaulted in payments of maturity notes. Ownership returned to the Patenotre family and Elverson Corp. Charles A. Taylor was elected president of The Inquirer Co. and ran the paper until it was sold to Moses L. Annenberg in 1936. During the period between Elverson Jr. and Annenberg The Inquirer stagnated, its editors ignoring most of the poor economic news of the Depression. The lack of growth allowed J. David Stern's newspaper, the Philadelphia Record to surpass The Inquirer in circulation and become the largest newspaper in Pennsylvania. The Inquirer-Daily News Building on North Broad Street.Under Moses Annenberg, The Inquirer turned around. Annenberg added new features, increased staff and held promotions to increase circulation. By November, 1938 Inquirer's weekday circulation increased to 345,422 from 280,093 in 1936. During that same period the Record's circulation had dropped to 204,000 from 328,322. In 1939, Annenberg was charged with income tax evasion. Annenberg pleaded guilty before his trial and was sent to prison where he died in 1942. Upon Moses Annenberg's death, his son, Walter Annenberg, took over. Not long after, in 1947, the Record went out of business and The Philadelphia Inquirer became Philadelphia's only major daily morning newspaper. While still trailing behind Philadelphia's largest newspaper, the Evening Bulletin, The Inquirer continued to be profitable. In 1948, Walter Annenberg expanded the Inquirer Building with a new structure that housed new printing presses for The Inquirer and, during the 1950s and 60s, Annenberg's other properties, Seventeen and TV Guide.[2] In 1957 Annenberg bought the Philadelphia Daily News and combined the Daily News' facilities with The Inquirer's. A thirty-eight day strike in 1958 hurt The Inquirer and, after the strike ended, so many reporters had accepted buyout offers and left that the newsroom was noticeably empty. Furthermore, many current reporters had been copyclerks just before the strike and had little experience. One of the few star reporters of the 1950s and 60s was investigative reporter Harry Karafin. During his career Harry Karafin exposed corruption and other exclusive stories for The Inquirer, but also extorted money out of individuals and organizations. Karafin would claim he had harmful information and would demand money in exchange for the information not being made public.[6] This went on from the late 1950s into the early 60s before Karafin was exposed in 1967 and convicted of extortion a year later. By the end of the 1960s, circulation and advertising revenue was in decline and the newspaper had become, according to Time magazine, "uncreative and undistinguished."[3] In 1969 Annenberg was offered US$55 Million for The Inquirer by Samuel Newhouse, but having earlier promised John S. Knight the right of first refusal of any sale offer, Annenberg sold it to Knight instead. The Inquirer, along with the Philadelphia Daily News, became part of Knight Newspapers and its new subsidiary, Philadelphia Newspapers Inc. Five years later, Knight Newspapers merged with Ridder Publications to form Knight Ridder. When The Inquirer was bought, it was understaffed, its equipment was outdated, many of its employees were under skilled and the paper trailed its chief competitor, the Evening Bulletin, in weekday circulation. However, Eugene L. Roberts Jr., who became The Inquirer's executive editor in 1972, turned the newspaper around. Between 1975 and 1990 The Inquirer won seventeen Pulitzers, six consecutively between 1975 and 1980, and more journalism awards than any other newspaper in the United States. Time magazine chose The Inquirer as one of the ten best daily newspapers in the United States, calling Roberts' changes to the paper, "one of the most remarkable turnarounds, in quality and profitability, in the history of American journalism."[3] By July 1980 The Inquirer had become the most circulated paper in Philadelphia, forcing the Evening Bulletin to shut down two years later. The Inquirer's success was not without hardships. Between 1970 and 1985 the newspaper experienced eleven strikes, the longest lasting forty-six days in 1985. The Inquirer was also criticized for covering "Karachi better than Kensington".[3] This did not stop the paper's growth during the 1980s, and when the Evening Bulletin shut down, The Inquirer hired seventeen Bulletin reporters and doubled its bureaus to attract former Bulletin readers. By 1989 Philadelphia Newspapers Inc.'s editorial staff reached a peak of 721 employees. The 1990s saw gradually dropping circulation and advertisement revenue for The Inquirer. The decline was part of a nationwide trend, but the effects were exascerbated by, according to dissatisfied Inquirer employees, the paper's resisting changes that many other daily newspapers implemented to keep readers and pressure from Knight Ridder to cut costs.[4] During most of Roberts' time as editor, Knight Ridder allowed him a great deal of freedom in running the newspaper. However, in the late 1980s, Knight Ridder had become concerned about The Inquirer's profitability and took a more active role in its operations. Knight Ridder pressured The Inquirer to expand into the more profitable suburbs, while at the same time cutting staff and coverage of national and international stories. Staff cuts continued until Knight Ridder was bought in 2006, with some of The Inquirer's best reporters accepting buyouts and leaving for other newspapers such as The New York Times and The Washington Post. By the late 1990s, all of the high level editors who had worked with Eugene Roberts in the 1970s and 80s had left, none at normal retirement age. Since the 1980s, the paper has won just one Pulitzer, a 1997 award for "Explanatory Journalism." In 1998 Inquirer reporter Ralph Cipriano filed a libel suit against Knight Ridder, The Philadelphia Inquirer and Inquirer editor Robert Rosenthal over comments Rosenthal made about Cipriano to The Washington Post. Cipriano had claimed that it was difficult reporting negative stories in The Inquirer about the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Philadelphia and Rosenthal later claimed that Cipriano had "a very strong personal point of view and an agenda...He could never prove [his stories]." The suit was later settled out of court in 2001. Knight Ridder was bought by rival The McClatchy Company in June 2006. The Inquirer and the Philadelphia Daily News were among the twelve less-profitable Knight Ridder newspapers that McClatchy put up for sale when the deal was announced in March.[11] On June 29, 2006 The Inquirer and Daily News were sold to Philadelphia Media Holdings L.L.C., a group of Philadelphian area business people, including Brian P. Tierney, Philadelphia Media's chief executive. The new owners planned to spend US$5 million on advertisements and promotions to increase The Inquirer's profile and readership. In the months following Philadelphia Media Holding's acquisition, The Inquirer has seen larger than expected revenue losses, mostly from national advertising. The revenue losses caused management to cut seventy-one editorial staff members in the first month of 2007. History from Wikipedia and OldCompanyResearch.com.

About Specimens Specimen Certificates are actual certificates that have never been issued. They were usually kept by the printers in their permanent archives as their only example of a particular certificate. Sometimes you will see a hand stamp on the certificate that says "Do not remove from file". Specimens were also used to show prospective clients different types of certificate designs that were available. Specimen certificates are usually much scarcer than issued certificates. In fact, many times they are the only way to get a certificate for a particular company because the issued certificates were redeemed and destroyed. In a few instances, Specimen certificates we made for a company but were never used because a different design was chosen by the company. These certificates are normally stamped "Specimen" or they have small holes spelling the word specimen. Most of the time they don't have a serial number, or they have a serial number of 00000. This is an exciting sector of the hobby that grown in popularity over the past several years.

Certificate Vignette

About Specimens Specimen Certificates are actual certificates that have never been issued. They were usually kept by the printers in their permanent archives as their only example of a particular certificate. Sometimes you will see a hand stamp on the certificate that says "Do not remove from file". Specimens were also used to show prospective clients different types of certificate designs that were available. Specimen certificates are usually much scarcer than issued certificates. In fact, many times they are the only way to get a certificate for a particular company because the issued certificates were redeemed and destroyed. In a few instances, Specimen certificates we made for a company but were never used because a different design was chosen by the company. These certificates are normally stamped "Specimen" or they have small holes spelling the word specimen. Most of the time they don't have a serial number, or they have a serial number of 00000. This is an exciting sector of the hobby that grown in popularity over the past several years.