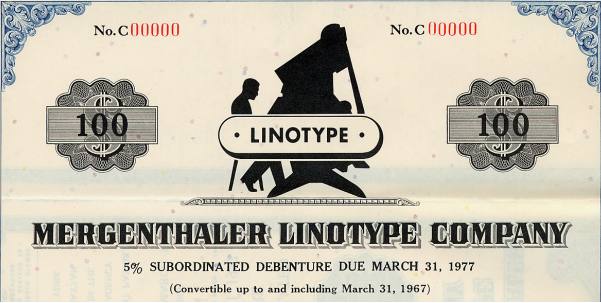

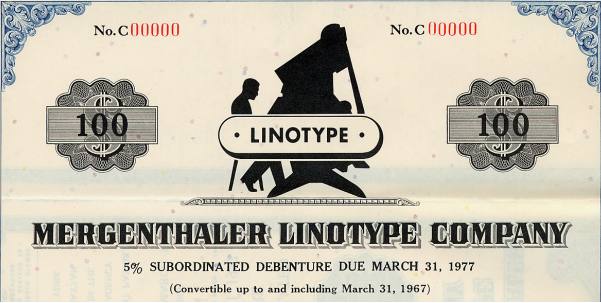

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Mergenthaler Linotype Company issued in 1962. This historic document was printed by American Bank Note Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of man sitting at a linotype machine. This item has printed signatures by the Company's President and Secretary and is over 43 years old. 30 coupons attached on right not shown in scan.

Certificate Vignette Ottmar Merganthaler was born on the 11th of May, 1854 in the tiny German village of Hachel. Arriving in Baltimore in 1872, Merganthaler took a job in the Hahn Company machine shop, which produced models for the U.S. Patent office, it was here that he met James O. Clephane. Clephane was a Supreme Court reporter and former secretary to William H. Seward who was part of President Lincoln's cabinet during the Civil War. Clephane was an early developer of shorthand writing systems and a proponent of the first typewriters. Seeking a way to quickly and efficiently reproduce his typewritten documents he recruited Merganthaler. After several years of painstaking work Merganthaler developed a machine which combined the tasks of casting and setting type. First patented in 1884 and used commercially in 1886 at the New York Tribune, Merganthaler's invention became known as the Linotype. The machine had long vertical parallel bars, each bearing a complete alphabet of metal type or dies, and a fingerboard by which the selected letters for a line, one on each bar, could be brought into alignment and impressed in papier-mache, thus producing one after another justified matrix lines; the papier-mache matrices thus produced being transferred to a second machine from which the slugs or linotypes were cast, one at a time, line after line. In October, 1891, a new company, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company of New York, was formed and succeeded to the holdings of the older companies. The Mergenthaler Printing Company and the National Typographic Company had expended upward of two million dollars and had exhausted their capital. The new company was provided with a cash capital of only $374,000, and it was with this limited capital that Mr. Dodge was required to reestablish and carry on the business. The first dividend was not paid until August, 1894. The Linotype Company had Mr. Philip T. Dodge, of Washington, as president and general manager. Mr. Dodge was a young patent attorney of Washington, and had prepared and solicited the patents on the Linotype from a very early period. He took hold of the business as president and general manager in November, 1891. The There was no ownership of real estate. The tool equipment was limited and imperfect, and the factory consisted of a small leased building. The machine at that time was far from perfect and worked in a more or less unsatisfactory fashion. He had the opposition of those who feared that their trade would be ruined, and of those who were skeptical in view of the vast sums that had been lost in the typesetting machine business. Linotype machines revolutionized the printing industry in the late 19th century. Newspapers and print shops throughout the world were quick to adopt Merganthaler's invention. The increases in efficiency brought about by the Linotype machine greatly reduced the cost of printed material making things like books, newspapers and magazines available to a much larger populace. Continuous improvements have been made to the Linotype throughout the years as evidenced by the over 1000 linotype related patents taken out. Linotypes were a mainstay of the printing industry through the better part of the 20th century and are still in use in some print shops today. The early 1890s was a period when newspaper, book, and magazine printers tried out the new composing machines entering the market. Various contests and demonstrations were held, with the Linotype usually producing the best records. Organized labor initially had qualms about a machine that they feared would put its printers out of work, but by 1900 their objections had largely subsided as union printers had taken control of the machines and the demand for printed material had increased. Both before and after Mergenthaler's death, the Mergenthaler company defended its patents against interference and infringement by competing machines. It also bought out a competitor in 1895 to obtain patent rights for the crucial double-wedge spaceband used in justifying the lines of type. The Linotype thus "held the field" until after the inventor's principal patents expired and the competing Intertype was introduced in 1913. Linotypes were extensively improved over the years as installation proceeded in a majority of the nation's printing plants. The hot-type systems using them began their decline after World War II. Intense labor problems and the adoption of offset printing and cold-type photocomposition methods (and later computers) coincided with publishers' desires for lower costs. The Mergenthaler company ended U.S. production in 1971 after building nearly 90,000 Linotypes. Probably a few thousand were still in use in the United States in the early 1990s. The Merganthaler Linotype Company continued until 1987 when a company from Germany acquired it and its name was changed to Linotype AG. History from Linotype Organization.

About Specimens Specimen Certificates are actual certificates that have never been issued. They were usually kept by the printers in their permanent archives as their only example of a particular certificate. Sometimes you will see a hand stamp on the certificate that says "Do not remove from file". Specimens were also used to show prospective clients different types of certificate designs that were available. Specimen certificates are usually much scarcer than issued certificates. In fact, many times they are the only way to get a certificate for a particular company because the issued certificates were redeemed and destroyed. In a few instances, Specimen certificates we made for a company but were never used because a different design was chosen by the company. These certificates are normally stamped "Specimen" or they have small holes spelling the word specimen. Most of the time they don't have a serial number, or they have a serial number of 00000. This is an exciting sector of the hobby that grown in popularity and realized nice appreciation in value over the past several years.

Certificate Vignette

About Specimens Specimen Certificates are actual certificates that have never been issued. They were usually kept by the printers in their permanent archives as their only example of a particular certificate. Sometimes you will see a hand stamp on the certificate that says "Do not remove from file". Specimens were also used to show prospective clients different types of certificate designs that were available. Specimen certificates are usually much scarcer than issued certificates. In fact, many times they are the only way to get a certificate for a particular company because the issued certificates were redeemed and destroyed. In a few instances, Specimen certificates we made for a company but were never used because a different design was chosen by the company. These certificates are normally stamped "Specimen" or they have small holes spelling the word specimen. Most of the time they don't have a serial number, or they have a serial number of 00000. This is an exciting sector of the hobby that grown in popularity and realized nice appreciation in value over the past several years.