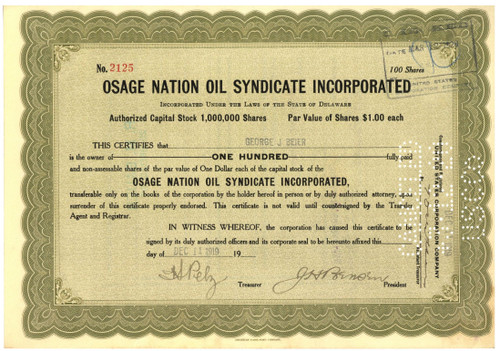

Osage Nation Oil Syndicate Incorporated - 1919. The company had leases on 2360 acres of land in Osage County, Oklahoma.

Killers of the Flower Moon is a 2023 American epic western crime drama film directed and co-produced by Martin Scorsese, who also co-wrote the script alongside Eric Roth, based on the 2017 non-fiction book of the same name by David Grann. Set in 1920s Oklahoma, it focuses on a series of murders of Osage members and relations in the Osage Nation after oil was discovered on tribal land. The tribal members had retained mineral rights on their reservation and White opportunists sought to gain their wealth.

Already rich from leases of their grazing lands, the Osage grew exponentially more wealthy after the discovery of oil on their lands. In 1895 Henry Foster of Kansas acquired a blanket lease that covered the entire Osage Reservation, more than 1.5 million acres. When Henry died, his brother, Edwin, took charge of developing the "Foster lease." Unable to begin drilling for some time due to financial woes, Edwin Foster in 1896 organized the Phoenix Oil Company, which he reorganized into the Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Company (ITIO) before his death in 1901.

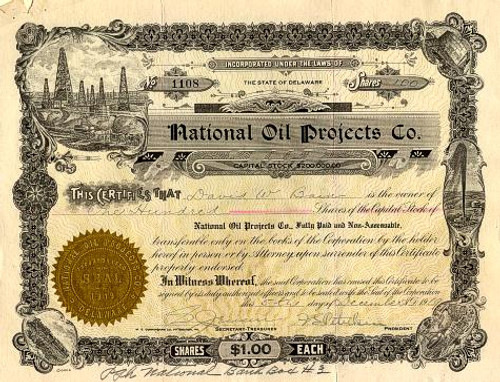

Petroleum development in the Osage Reservation, which is part of the vast Mid-Continent oil and gas region, proceeded slowly in the late 1890s. Inadequate transportation, declining prices for oil, and other problems caused further delays. Only after the turn of the twentieth century were producing wells brought in. Beginning with a successful first well near Bartlesville, only forty wells had been completed by 1903. In 1904 a pipeline was constructed to the Standard Oil Refinery in Neodosho, Kansas, reducing transportation costs by nearly 40 percent. The next year over three hundred wells were brought into production. In 1907 the Osage oil fields produced more than five million barrels.

Over the next two decades the Osages' "underground reservation" would produce more wealth than had all of the American gold rushes combined. The Foster lease was renewed for ten years in March 1906, but ITIO lost sole rights to drill in 1916. Thereafter, leasing on a competitive basis was then allowed on tracts of land up to five thousand acres in size.

Public lease auctions began in 1916, most of which occurred in Pawhuska under the Million Dollar Elm tree with Colonel Ellsworth Walters as auctioneer. The record bid was $1,990,000 for a single, 160-acre tract. Development that had begun in the eastern half of the county gradually worked westward. One of the richest, best known of the Osage County areas was the Burbank Field, developed in the 1920s by Marland Oil Company and future governor Ernest W. Marland. Burbank alone produced more than 103 million barrels in 1926. By 1930 more than three dozen Osage oil fields existed, including Avant, Barnsdall, and Skiatook, and from 1901 through 1930, 319 million barrels of Oklahoma crude were pumped from the ground in Osage County.

In the process of developing the Osage oil fields, the boomtown phenomenon occurred. Existing towns such as Pawhuska, Hominy, Fairfax, Grainola, and Bartlesville bustled with activity. Populations burgeoned, at least until the oil played out. Oil camps and new towns, such as Wolco, named for the Wolverine Oil Company plant, Tallant, site of a refinery named for a Cities Service executive, and Carter Nine, named for the Carter Oil Company, appeared overnight all over the district. One of the most famous, located in the Burbank Field, was Whizbang (now called DeNoya), named for a popular magazine called Captain Billy's Whiz Bang. Most of these, too, declined as the boom ended, and many became ghost towns.

Unlike other landholders, the Osage were able to retain collective ownership of subsurface mineral rights, rather than having to accept allotments to individual owners. Instead, tribal members received "headrights" that assured them an equal share of mineral rights sales equivalent to income from 658 acres. A headright could not be sold, but an individual could sell his or her surface rights. An average Osage family of a husband, wife, and three children would receive more than $65,000 a year in 1926, and by 1939 Osage individuals had received a total of more than $100 million in royalties and bonuses.

Oklahoma Historical Society