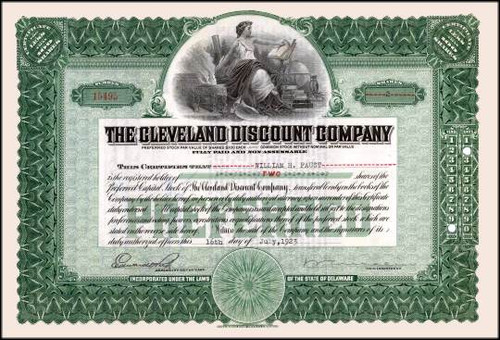

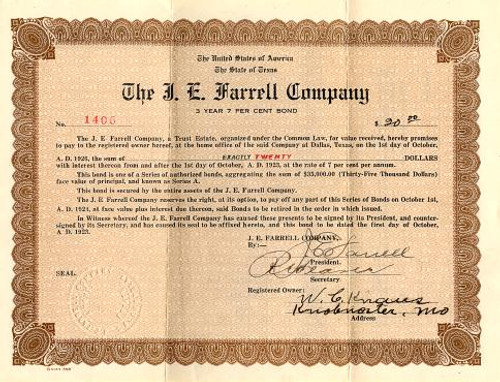

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Philip Mead Bat Company issued in 1923. This historic document has an ornate border around it. This item is hand signed by the Company's Directors and Secretary and is over 80 years old. Cricket bat company named after the famous player, Philip Mead. Mead, Charles Philip (1887-1958) The Man who Never Encouraged Bowlers (by John Arlott) He was never much concerned with records. But, pressed to choose one for himself, I have little doubt that he would have picked that which, in fact, stands to his name - with no indication that it will ever be wrested from him. That record is for the greatest number of runs scored by any player for one team in the entire history of cricket. The number is 48,892, scored by Philp Mead for Hampshire. The figure is staggering. He would have liked us to make that comment. he would have pointed out, though, that he did not only bat for Hampshire; that, in all first-class matches, he totalled 55,061 runs, with 153 centuries and an average of 47.67. But for four seasons lost to the First World War, he must have made atleast 8,000 more. His first-class career is given officially as from 1905 to 1936: but in 1905, while he was qualifying for Hampshire, he played in only one match. so his runs were made in twenty-seven seasons: an average of more than 2,000 runs a year. We may adduce one more piece of evidence about him before we dispense with "damned dots" - Mead's average in Test cricket against Australia (51.87 in, surprisingly enough, only seven Tests, and jthose spread over seventeen years) is higher than his figure for all play. No one who saw Philip Mead bat will ever forget him. At the fall of Hampshire's second wicket he would emerge from the pavilion with a peculiar rolling gait, his sloping shoulders, wide hips and heavy, bowed legs giving him the bottom-heavy appearance of those lead-based, won't-fall-down dolls of our childhood. Leath- ery complexioned, with a long nose, a wry expression and eyes which seemed always to be screwed up against the sun, he had a semi-comic air: but he was a very serious batsman. At the crease, he went through precisely the same ritual before every ball was bowled to him. First he touched his cap four times to short-leg (whether that fieldsman was there or not) then he tapped his bat four times in the crease and, finally, took four small, shuffling strides up to it. Then, and only then, the bowler might bowl: if he tried to do so before the ritual was completed, Philip stepped away from his stumps and, when the bowler stopped, started the whole procedure over again. He wore out some dozens of cap-peaks in his time, and - "I know it some- times held them up; but is used to put some of the hasty ones off, and I shouldn't have felt happy if I hadn't done it." His batting gave a superficial impression of clumsiness, accen- tuated perhaps by the fact that he was left-handed. But his footwork was so neat that he seemed always in position, his bal- ance was utterly perfect and his timing so delicate that he seemed only to need to stroke the ball to send if for four. One of his maxims was: "No point in trying to bash the case off it: just hit it hard enough for four." He had all the strokes and, though he relished the cover-drive ("that's everyone's favourite stroke, really"), he never favoured any to the extent of playing it to the wrong ball. The best critics of batsmen - the bowlers of four countries, who opposed him over three decades - described him, with remarkable unanimity, as "the hardest of them all to get out". That was the way he wanted to be. Alec Kennedy, who knoew him better than anyone, thought the most remarkable facet of his batting was that he made so many of his big scores on turning wickets. Yet Alec added, "But he was as fine a player of fast bowling as I ever saw." That judgment was borne out when Mead stopped the terrify- ing progress of Gregory and McDonald, the Australian fast bowlers of 1921, in the Fifth Test with an innings of 182 (not out), then the highest score ever made by an English batsman against Aus- tralia in England. There probably will be no end - and can be no clear decision - to the debate as to whether Philip Mead or Frank Woolley was te greater left-hand batsman. There is no doubt that Woolley was the greater stylist, and he scored more runs: but Mead had the higher average - over all, and against Australia - and, by his standards, that would be conclusive. This man, Charles Philip Mead - "Phil" - was the ultimate run- hungry batsman. Indeed, at times it seemed that he was not in- terested in batting but only in runs. Like the Sikhs, who only draw their knives to draw blood, he did not care to pick up his bat except to oppose a bowler for runs which counted. He had a rooted aversion to batting in the nets: and, when others took pre-season practice, he would do his utmost to evade it, with words, "You may lead in May, but I shall catch you in June."Once, when he voiced dissatisfaction with his timing in a century which was his first innings of the season, Alec Kennedy pertinently en- quired when he had last held a bat in his hands. "Last Scarbor- ough Festival," was the the answer. Mead was consciously, and quite downrightly, a *professional* cricketer: he executed his craft for the best living he could get (and that was fairly meagre); and he would not, I fancy, have objected to being described as a mercenary. Hampshire, in his day, paid talent money to their batsmen strictly on a basis of fifty-run increments, irrespective of their effect on the match. So, an innings of 49 went worthless financially: one of 99 no better rewarded than 50. Hence, more than one Hampshire batsman was run out when Philip had the strike on 49 or 99: and one famous left-arm bowler, an old opponent recalls the many times when Mead steered him through the short-leg fieldsmen and, as he completed the stroke, set off for a run with the words, "That's another ton of coal for the winter." It is not unusual to hear it said that Mead was a slow scorer; but the records do not bear out that argument. He could *look* slow because his movement to the ball was so unhurried, and be- cause he never seemed to swing the bat: he came by his runs at a steady but unobtrusive rate. Perhaps the illusion was best demonstrated, in all innocence, by an old Hampshire member who said to me, "Of course Mead was so dull: I once saw him stonewall nearly all day for 280!" In truth, he scored as fast as he could, consonant with his assessment of safety. I have called him run-hungry, but it might be more accurate to describe him as a run addict. Many batsmen, when they have made a century - or 150 or 200 - will take risks and, in effect, throw away their wickets. But the more runs Philip Mead made, the more he wanted. In 1912, when Hampshire were in a losing position against Warwickshire, he saved them in the second innings with 207 not out, scored in exactly three hours. The next day, against Sussex at Portsmouth, he made a century before lunch and, when Bob Relf caught him at cover for 194 in mid-afternoon, came into the dressing-room with the words, "I didn't get over it properly." Once in scoring vein he would go on and on, combative, acquisi- tive, never losing poise, power or patience. Between early June and mid-July in 1921 he scored 1,601 runs; a year later he made 1192 in seven consecutive innings: in 1927, from the end of May to late June, he played fourteen innings (four of them not out) for 1,257 runs (an average of 125.70): he was then forty years old. For several years before he retired he was so crippled by rheuma- tism and backache that he could barely stoop to lace his boots. But still the runs came and he still caught almost anything within his reach at slip, though he would not care to run for the snicks that scuttled past him. To the end, even on the eve of his blindness - such an ironically savage blow to fall upon one of his keen eye for the ball - he batted with monumental skill and soundness. It was Mead's dishearteningly broad bat that changed Maurice Tate from a slow off-spinner to a pace bowler. In desperation, against that unwavering defence, one afternoon at Horsham, Tate gathered all his energy and flung down the first quick ball he had ever bowled in all his life. It pitched on Mead's off-stump, made hurry off the pitch and flicked away the leg bail. So Tate described it; thirty years later, Mead, unprompted, confirmed the description. "A pretty good ball, Philip?" "Not half: a real trimmer: mind, I don't say I wouldn't have played it if I'd ex- pected him to bowl fast ... but, yes, it was a good 'un." "Did you say anything to him, Philip?" "What? Me? 'Course I didn't. I never encouraged bowlers." That might be Philip Mead's epitaph as a cricketer: pre- eminently among all the men who ever wielded a bat, he never en- couraged bowlers. (Thanks : "The Boundary Book", ed. Leslie Frewin, McDonald, 1962)

Philip Mead Bat Company - 1923

MSRP:

$239.95

$199.95

(You save

$40.00

)

- SKU:

- phmebatco19

- Gift wrapping:

- Options available