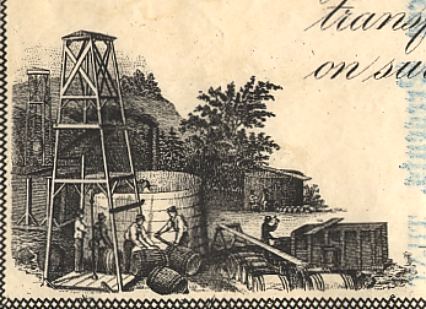

Beautifull stock certificate from Story & McClintock Petroleum Company issues in 1864. This historic document was printed by R.C. Root, Anthony & Co,16 Nassau St. New York and has an ornate border around it with a vignettes of an eagle and an old oil derrick. This item has the signatures of the Company's President, R. C. Root and Secretary.

Certificate Vignette

Certificate Vignette Along Oil Creek, just south of Titusville, Colonel Edwin Drake struck oil at a depth of 69.5 feet in August 1859. Drake's Well marks the birth of the world's oil industry. The history of Venango County is inextricably connected with oil, for it was here that the oil industry began.The oil industry traces its roots to Titusville, just across the border in Crawford County, for it is there that Col. Edwin L. Drake drilled the first oil well, thereby setting into motion a chain of events that resulted in the creation of one of the mightiest industries the world has ever known. The Pennsylvania oil region had an apocryphal "history" of fire on water supposedly written by the French Commander of Fort Duquesne in a letter to His Excellency, General Montcalm. This particular letter turned out to be fiction. It was published in the early 1840s, but is repeated here because what an effect it had! It said: "While descending the Allegheny, fifteen leagues below the mouth of the Conewango, and three above Venango, we were invited by the Chief of the Senecas to attend a religious ceremony of his tribe. Gigantic hills begirt us on every side. The Great Chief recited the conquest and heroism of their ancestors. The surface of the stream was covered with a thick scum, which burst into complete conflagration. The oil had been gathered and lighted by a torch. At the sight of the females, the Indians gave forth the triumphant shout that made the hills echo and re-echo again. Here, then, is revived the ancient fire worship of the East. Here, then, are the Children of the Sun." (F.W. Beers, 1865 Atlas of the Oil Region of Pennsylvania) The region they described was probably the Oil Creek Valley in Venango County, Pennsylvania, about 100 miles north of Pittsburgh. It was on the banks of this creek that Col. Edward L. Drake drilled three wells, the first in 1859. It was this event that signaled the birth of the oil industry. A key figure in the founding of the industry was George H. Bissell, a graduate of Dartmouth and a lawyer in New York City, When he saw a bottle of petroleum obtained from an area near Titusville where oil seeped out of the ground, he realized it could be used as an illuminant. Aroused by the prospect, Bissell and his business partner, Jonathan G. Eveleth, decided if they could find a good supply of petroleum, they would organize a company, buy the land, develop the spring and market the petroleum. Thus, on Nov. 30, 1854, Bissell and Eveleth purchased the Hibbard farm, on which the principal petroleum springs in northwestern Pennsylvania were located, from Brewer, Watson and Company of Titusville, for $5,000. The following month they organized the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of New York, the first petroleum company in the world. However, because of hard times they found it difficult to sell stock. In April, 1855, Professor Benjamin Silliman, Jr., of Yale College, whom the promoters had hired to analyze the oil, made his report and pointed out its economic value. This proved to be a turning point in the establishment of the petroleum industry. A number of New Haven capitalists were impressed by Silliman's report and agreed to buy stock, provided the company was reorganized under the liberal corporation laws of Connecticut. This prompted Eveleth and Bissell to abandon their original enterprise and formed instead the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of Connecticut on Sept. 18, 1855, with a capital stock of $300,000. The original company sold the Hibbard farm to the new company. Little progress was made until one day Bissell saw a bottle of rock oil in a drugstore window in New York City. He conceived the idea of drilling for petroleum, as Kier had drilled for salt. He persuaded Lyman and Havens, prominent Wall Street real investment brokers, to lease the Hibbard farm and drill for oil, but before they could begin, the Panic of 1857 overwhelmed them. Taking advantage of a technicality, they surrendered their lease. James M. Townsend, now president of the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company, decided that he and his New Haven associates should organized a company, assume the lease, drill for oil and monopolize the oil business. Accordingly, the formed the Seneca Oil Company on March 23, 1858 with a capital of $300,000, leased the Titusville property from the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of Connecticut, elected Edwin L. Drake as General Agent and sent him to Titusville in the spring of 1858 to drill for oil. After many unavoidable delays and after overcoming numerous obstacles, Drake began drilling in the summer of 1859. On a Saturday afternoon, Aug. 27, as Drake and his men were about to quit work, the drill dropped into a crevice at a depth of 69 ft. They then pulled out their tools and went home without any thought of having struck oil. Late Sunday afternoon, the driller, William A. Smith, visited the well, peered into the pipe and saw a dark fluid floating on top of the water. Oil had been struck! Drake had demonstrated a way to secure oil in great abundance. He had tapped the vast subterranean deposits of petroleum underneath the Oil Creek valley, and, unknown to him at the time, had ushered in a new industry which not only provided the world with a safe and cheap illuminant but a source of unexcelled lubrication. News of Drake's accomplishment spread rapidly. Within 24 hours hundreds of people were milling around the Drake well. An eyewitness wrote that the excitement was fully equal to what he had seen in California at the time of the gold rush. Everyone was wild to lease or buy land and drill a well. The Boom Is On Because of the location of the Drake well, it was believed the best place was in the lowlands and as near as possible to the flowing waters of Oil Creek. Consequently, there was a mad rush to secure land near the Drake well and along the creek. Bissell bought all the stock of the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company that he could buy and then hurried to Titusville. He boldly leased or purchased farm after farm along Oil Creek and along the Allegheny River (Oil Creek enters the Allegheny at Oil City, Venango County). Land bordering Oil Creek was soon taken up and within a short time the entire valley, even far back into the hillsides, had been either leased or purchased. Col. Drake was advised to join the rush to purchase or lease land, but he rejected all counsel. When several other wells were struck, he realized his mistake, but by then it was too late. He ceased to be a factor in the oil industry. Others came in to take advantage of his achievement. William Barnsdall and Moone Meade of Titusville and Henry Rouse, a merchant from Enterprise, drilled the second well, on the Parker farm a short distance above the Drake Well. In November they struck oil, but the yield proved to be less than five barrels daily, so they resumed drilling. A few days later, when it was down 112 feet, oil rushed up and flowed over the top of the pipe at the rate of about 10 barrels. Barnsdall's well, as they called it, soon became the center of attention and the "lion of the valley". On the opposite side of Oil Creek from Drake Well and about a mile below, David Crossley of Titusville started drilling the third well. He struck oil March 14, 1860. With a pump it produced 75-80 barrels. "A splendid thing is the Crossley well!" declared Thomas A. Gate of Riceville. "A diamond of the fist water! Enough of itself to silence the cry of humbug; to create a sensation of rival interests or inspire hope in many toiling for subterranean treasure, and to make every son of Pennsylvania rejoice in the good Providence that has enriched the state, not only with vast mines of iron and coal but also with rivers of oil !" The oil rush was on! Hundreds of people poured into Titusville daily, but by no means was the excitement confined solely to the area around that community. Simultaneously with the drilling of the Barnsdall well, Brewer, Watson and Company started putting down a well on the McClintock farm at the lower end of Oil Creek, and in Nov., 1859 they struck oil. By the summer of 1860 at least 12 wells were underway in that area. E.E. Evans, a blacksmith in Franklin, cleaned out an old salt well near that community and when he struck oil, his well came in at the rate of a barrel an hour. This and another successful drilling venture stimulated a frenzy of drilling activity near Franklin. By August, 1860 over 100 wells were being drilled within a mile of the center of Franklin. And up the Allegheny River, at Tidioute, the excitement over new wells was at fever pitch by August, 1860. Oil speculators overran the town, everyone seemed half crazy and according to the Warren Mail, it seemed as though one-half of Warren's population had gathered at Tidioute. The town had three hotels and each had three times as many guests as they could comfortably accommodate. The production of the pioneer wells in 1859 amounted to about 2,000 barrels, but by the end of 1860 a remarkable change had occurred. By that time there were 74 producing wells, most along Oil Creek. Production amounted to 200,000 barrels for the year. All this production had an effect on price. In 1859 oil sold for 75 cents a gallon. By the end of the year the price had dropped as low as 22 cents a gallon. The pioneer wells of 1859 and 1860 produced more oil than anyone had ever seen, but they were nothing compared to the wells that came in beginning in 1861. A.B. Funk, a lumberman from Warren County, Pennsylvania, completed a well on the David McElhenny farm, seven miles below Titusville, in May, 1861. It commenced flowing at the rate of 300 barrels. Skeptics called it the "Oil Creek humbug" and expected the flow would soon cease, but they waited it vain. It continued flowing for 15 months, then suddenly quit and never produced another barrel, but no matter, by that time it had earned for Funk $2,500,000 (he had paid $1,500 for the farm in 1859). The Empire well on the same farm and near the Funk well, completed in September, 1861, flowed at the rate of 3,000 barrels! Unable to secure barrels, the owners tried to check the flow, but without success. The built an enclosure around the well, but the oil refused to be dammed and flowed into Oil Creek. The creek was covered with the resultant oil skim for miles. The yield from this well simply bewildered the owners. This well was too productive. With the market already glutted, this well was adding 3,000 barrels a day to the daily supply. The Empire well drove the price down to 10 cents a barrel. Within a few weeks after the Empire started flowing, it was eclipsed by a new well on the James Tarr farm at the lower end of Oil Creek. William Phillips, a salt well driller from the Pittsburgh area, had secured a lease on this farm and during the summer of 1861, started drilling. He drilled two successful wells of which the second produced 4,000 barrels daily. The flow was so great the owners built underground wooden tanks in which to store the oil. In time these tanks covered several acres. About four rods away N.S. Woodford drilled another well which began flowing 1,500 barrels in July, 1862. Water from this well soon flooded Phillips No. 2 and materially reduced the flow of oil from the latter. A peculiar condition developed where neither well would produce oil unless both were pumped at the same time. The owners thus negotiated an agreement whereby both wells were pumped simultaneously and each would get one-third of the production of the other well. South of the Tarr farm was the Blood farm and to the west the Story farm, both of which developed flowing wells. In 1861 the Blood farm had 12 wells, some of which were very heavy producers. The Story farm had been purchased for $40,000 by some Pittsburghers who later organized into a joint stock company. Andrew Carnegie was was of the principal stockholders in this firm, the Columbia Oil Company. Dividends from oil helped Carnegie erect his new steel mills. Because of these new wells, produced jumped to 5,000 barrels per day in 1861. This was both good and bad. Faced with a fabulous supply but only limited demand, the price of oil fell rapidly. By the end of the year, oil was selling for 10 cents a barrel. The owners of pumping wells were the most discouraged. Those with wells pumping 5-25 barrels per day were disheartened when an adjoining well sprouted hundreds of barrels, flooding the market and making the operation of pumping wells unprofitable. Faced with economic crisis, some of the landowners and operators of wells met at Rouseville (just north of Oil City, PA) Nov. 14, 1861 to organize and take measures to improve the price of oil. They formed the "Oil Creek Association", decided that an inspector should be elected to regulate the production of flowing wells, that oil should not be sold for less than 10 cents per gallon and that the proceeds should be paid into a general treasury, where it would be held for the order of the seller, less a certain percentage. By January 1862 this first great combination of producers had been organized and they refused to sell oil below $4 a barrel. Since the price of oil remained low during the first half of 1862, operators of limited means were either ruined or forced to sell. Production fell from 7,000 barrels to 4,000. This decline, coupled with increased use of oil at home and abroad, drove prices up again. By the end of the year oil was selling at $4 a barrel. The condition of the producers improved. It was not necessary to have a very large flowing well to reap a fortune. At this time Orange Noble and George B. Delamater, merchants from Townville, struck oil on the Farrell farm. Their well, a gusher, sprayed oil and water 100 feet into the air when it came in, enveloping the derrick and nearby trees in a dense spray. The gas flowed like a hurricane, the ground shook and oil flowed at the rate of 3,000 barrels. For days oil flowed into the creek. Men wearing goggles and rubber blankets eventually attached a stopcock, which eventually brought it under control. With oil at $4 a barrel and steadily increasing, Noble and Delamater's daily receipts varied from $12,000 to $45,000. Their well flowed for 18 months and netted the owners over $5 million. Their total expenditures for the lease, drilling, machinery and labor amounted to only $4,000, thus, every dollar they invested netted them a profit of over $15,000! Although new wells added to the production, the amount of oil produced during the first part of 1863 decreased materially. By that time few new wells were being drilled, production from the older, larger wells was falling off and the small wells pumped only 10-60 barrels per day. Besides, Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania in June caused such an excitement there was almost a total suspension of business in the oil fields for several days. With a decline in production and an increase in demand, the price soared. Oil reached $7.25 a barrel in September and buyers swarmed all over the region. Up to this point the drilling activity had been confined to the lowlands. In 1864, this changed. Two employees of the Humboldt Refinery at Plumer conceived the daring idea of drilling on land far removed from Oil Creek. In the spring of 1864 they leased 65 acres of the Thomas Holmden farm, located on an upland plateau, 5 1/2 miles from the creek. People thought these two men were insane. They formed the United States Petroleum Company and selected their first drilling site by dowsing with a twig of witch hazel. Their well was spudded in late 1864 and was dubbed the Frazier well. Before the well was finished, Thomas G. Duncan and George G. Prather bought the Holmden farm, subject to the lease, for $25,000. On Jan. 7, 1865 the Frazier well began to flow at 250 barrels a day. Stock in the U.S. Petroleum Company jumped from $6.25 to $40 a share. Excitement in the oil region was intense and drilling for another well was begun. In April, 1865 a Boston company completed a well known as the Homestead Well just 100 feet outside the boundary of the Holmden farm. It also flowed at the rate of 250 barrels. This prompted the region's wildest oil boom. The U.S. Petroleum Company divided its property into half-acre leases and sold more than 80 of them at an average of $3,000 each. At this same time the production of the Homestead well suddenly jumped to 500 barrels and the Frazier to 1,200. Excitement was at fever pitch and the leases doubled in price. A town that became famous in American industrial history, Pithole, was laid out nearby in May, 1865. So great was the speculative fever four months later it had a population of 15,000 and had the third largest post office in Pennsylvania. On June 17 the United States Company completed its second well. It flowed 800 barrels a day. Two days later a third well just above the original started flowing 400 barrels. By the end of June, 1865 the wells along Pithole Creek were producing 2,000 barrels a day, or one-third the total production of the oil region of 6,000 barrels - the total oil production in all the world at that time. Many factors fueled the Pithole oil boom. The end of the Civil War found the country flooded with paper currency whose holders were anxious to invest and make more money. Thousands of soldiers had been discharged from the army. Many wanted jobs, others wanted to make a fortune quickly after having spent long months on army pay. The speculative bubble of 1864 and 1865 was at its peak. Hundreds of newly-organized companies were ready to lease or buy land wherever there was even a promise of oil. Fired by these circumstances, the Pithole Creek became spectacular. In Pithole City land could not be bought, but only leased for three years with the privilege of removing the buildings when the lease expired or selling them to the owner of the land. If a five-year lease was desired, improvements and buildings had to be surrendered at the end. Most of the lots were leased quickly at the rate of $275 a year. When the frenzy was at its height, these leases were selling for $850 - and these were for lots that were only 33 feet wide. The surrounding forests disappeared quickly as the trees were cut and sawed for lumber to build the emerging boom town. The pace of construction was furious. Sometimes men entered into contracts to build a two-story building and had it completed and ready for occupancy within five days. This made for extremely flimsy construction. There was not one brick or stone building erected in all of Pithole. At its height Pithole had two banks, two telegraph offices, a daily newspaper, water works system, fire companies, two church buildings, scores of boarding houses, grocery stores, hardware stores, machine shops and other businesses. There were more than 50 hotels. The Chase Hotel was considered the best. Painted a nut brown color, it cost $80,000 and had a frontage of 180 feet. It could accommodate 200 guests and seat 100 in its dining room. One of the hotel's attractions was its salon, 65 feet long and 28 feet deep "furnished with a luxurious bar and hung with pictures." Murphy's Theater, the largest building in Pithole, had a seating capacity of 1,000. In addition to these elegant establishments there were numerous brothels, which catered to every variety of taste, pocketbook and social status. Every other building was a saloon, and every other man was a soldier, Confederate as well as Union. Every day at noon there was a scene unique to Pithole - the daily prostitute parade. Every day, 30-40 of the town's ladies of the night would mount horses and ride down the streets, garbed in their best high-necked gowns, hats and gloves. The men lining the route respected this elegant display by doffing their hats and refrained from making raucous comments or whistling. Drinking water was scarce. Much profit was made by persons who hauled water in and sold it for 10 cents a glass. As a result, saloons flourished. "Whiskey is cheaper to drink and a lot safer," observed one resident. If Pithole's rise was phenomenal, its fall was even more rapid. As oil production declined and parts of the town burned to the ground, the exodus from Pithole began. By the end of 1867 the town was, for all practical purposes, dead. That portion of the Holmden farm which at the height of the boom changed hands for $2,000,000 was bought by the Venango County Commissioners for $4.37 in 1878. Creating a Market for Petroleum It was Col. E. L. Drake himself who was the first oil marketer. Having discovered a rich supply of petroleum, in 1859 he contracted with Sam Kier of Tarentum to supply the latter with oil. Kier in turn promised to sell the oil in preference to any other that should come on the market, but should oil from other sources appear on the market, the price paid by Kier to Drake was to be reduced. Under this arrangement Drake shipped almost $3,800 worth of oil to Kier and over $5,000 worth to W. MacKeown, another oil distiller in Pittsburgh. Ferris, the New York petroleum dealer, wanted MacKeown to enlarge his distilling plant and take in the product of Brewer and Watson's well on the McClintock farm, which was then yielding about 20 barrels a day. The officers of the Seneca Oil Company expressed an interest in this plan and offered to sell to Ferris all oil they had to spare, if a satisfactory price could be agreed upon, and they agreed not to distill or sell to others. In return, they wanted Ferris and MacKeown to distill all the oil the Seneca people sold them. Under this arrangement, the Seneca people would control the crude oil and MacKeown and Ferris the refined. MacKeown's reluctance to accept this offer scuttled this plan. In order to introduce his product and solicit orders, Drake made a trip in Feb., 1860 to Erie, Chicago, Cincinnati and Pittsburgh, but he, as well as the New Haven stockholders, found oil difficult to sell. Some machinists recommended it highly as a lubricant, others were afraid the oil would injure their machinery, and they objected to the odor. While in Pittsburgh, Drake met George M. Mowbray, a chemist associated with the wholesale drug firm of Schieffelin Brothers and Company of New York. Mowbray saw the value of oil and the result was the two men struck a contract under which Drake agreed to ship to Schieffelins all the oil except what was already obligated from the wells of the Seneca Oil Company. In turn, Schieffelins guaranteed all sales, agreed to return all proceeds after deducting the charges, and for this service, they were to receive a commission of 7 1/2 percent. Although Drake had negotiated outlets through Kier, MacKeown and Schieffelins, the chief difficulty in trying to sell petroleum was its disagreeable odor, its impurities and its dark, muddy color. Petroleum needed to be deodorized, decolored and purified before it could be sold extensively, but there were no refineries except the small ones of Kier, MacKeown and Ferris. The Seneca Oil Company decided to go into the refining business, but internal dissension and bankruptcy prevented them from doing so. Nevertheless, after the completion of the Drake well, refineries sprung up almost instantaneously along Oil Creek and the Allegheny River, at Union Mills, Corry and Erie. W. H. Abbott, James Parker and William Barnsdall built the first refinery in Titusville in the fall of 1860. A large part of the machinery and appliances, purchased in Pittsburgh, were shipped up the Allegheny by boat to Oil City, thence up Oil Creek. When completed, the refinery consisted of six stills and bleachers, with all the tanks and fixtures under one roof. The first run of oil was made Jan. 22, 1861. The yield did not exceed 50 percent of the crude. Not knowing how to utilize the byproducts, they were either dumped into Oil Creek or burned all the tar and naptha. The number of refineries rapidly increased. The oil region had 15 refineries in 1860; by 1863 there were 61. Pittsburgh, which became the earliest refining center because of its location on the Allegheny River, had five large refineries in 1860. By 1863 it had 60, representing a capital investment of $1 million, employed 600 men and had a total weekly capacity of 26,000 barrels. Simultaneously with the expansion of the home market, petroleum was introduced to Europe. In 1860 the officers of the Seneca Oil Company sent samples to A. Gelee, a French chemist. After analyzing it, Gelee said, "If that oil can be gathered in quantity enough, its illuminating and lubricating qualities are such that for these purposes it will revolutionize the world." Although many Europeans saw its advantages, others, particularly the manufacturers of coal oil had strong prejudices against it. These manufacturers feared this new American product would put them out of business. It did. By 1862 The Times of London predicted that the value of the oil trade might approach that of American cotton. Europeans found it was a better illuminant, and cheaper, than olive oil. In 1862 oil was introduced into Russia. By 1863 the use of kerosene in lamps far exceeded that of tallow. "The people are becoming accustomed to it," reported the United States Consul at St. Petersburg in Dec., 1863. By the end of the Civil War oil had become America's sixth leading export, exceeded only by gold, corn, tobacco, wheat and wheat flour. Improvements in refining methods were made regularly. In 1860-61 Luther Atwood of the Downer organization introduced preheating. H. P. Gengembre of Pittsburgh introduced it differently. Atwood piped superheated steam into the still, while Gengembre sent preheated oil into the still. Outside the oil country, Giuseppe Tagliabue invented the flash and fire closed-cup method to enable refiners to determine the temperature at which oil makes enough vapor to form an explosive mixture with air. Joshua Merrill was the first to use sulfuric acid and alkali as a deodorizing the bleaching agent. In 1869 he discovered by accident how to refine an oil of heavy viscosity. He did it by carefully controlling the temperature, so that refining could take place without the oil decomposing or "cracking". By 1863 refineries located further from the oil producing region had increased to the point where their combined capacity exceeded 28,000 barrels per day. The New York City area had a capacity of 9,790, Baltimore had 1,098, Boston 3,500, but the biggest of all was the Cleveland area, which had a capacity of 12,732 barrels per day. In other parts of the nation refiners also made important contributions toward refining skills. In 1866 Hiram Everest introduced the vacuum still at Rochester, NY using lower temperatures, thus preventing "cracking" or decomposition. To handle crude oils containing sulfur Herman Frasch in 1886 introduced metallic oxide to solve the problem of sulfur removal. As refining methods improved, new products were introduced. Lighter napthas served as solvents, cleaning agents and turpentine substitutes; gasoline was employed in air-gas engines as early as 1863; liquefied petroleum gases were discovered in 1866 and used in medicine and in compression machines used to make ice. Paraffin wax and petrolatum (petroleum jelly) were also valuable byproducts. Transporting petroleum to market was very difficult at first. Oil Creek itself served as the original means of transportation. Oil was loaded on flatboats and floated downstream, but highwater stages occurred only six months out of the year. The rest of the time, the oilmen utilized the pond freshet, a method loggers had used for years to float their logs downstream. To create the pond freshet there were at least 17 sawmills with dams on the principal branches of Oil Creek. Through a system of floodgates, the water could be held up until a sufficient quantity was backed up, then it was let loose to create a swell of water big enough to float the logs downstream. As the pond freshet passed, the cuts in the dams were closed and the water was held again until enough logs had been sawed to warrant another freshet. The oilmen saw immediately this could become a viable method for them to get their oil downstream. Accordingly, the struck deals with the sawmill operators for use of their dams. The latter charged fees which increased as the demands for water by the oilmen got more frequent. During the busy season, pond freshets were provided twice a week. The superintendent set the date and notified shippers and boatmen well in advance, so that they could overhaul their flatboats and tow them to a point on the creek to be loaded. The boats were of all sizes and kinds, most could hold 700-800 barrels. They carried the oil either in bulk or in barrels. A cool breeze was the first sign of the freshet's approach and the swirling waters soon followed. Expectant boatmen stood ready to cast off their lines when the current was precisely right. Inexperienced boatmen generally cut their boats loose too soon. Their boats became grounded and were battered into kindling by those coming later. An experienced boatman waited until the water began to recede, then he cut loose his lines, throwing himself onto the mercy of a swift current. Imagine. On each freshet there were 150 to 200 flatboats, all loaded with oil either in barrels or in bulk, floating endways or sideways, all trying to wend their way down Oil Creek, a stream that was only 12 rods wide and very crooked as it wound its way past steep hills. It required boatmen of considerable skill to avoid collisions with other boats, rocks and other obstructions. If a boat got crosswise on the creek a jam often occurred. The boats, built of light timber, were easily crushed and the oil spilled into the creek. If the oil was in barrels the boat sank, the barrels floated off and the owner rarely recovered all of them. If the boats successfully passed these obstacles, they still had to get to Oil City, where Oil Creek emptied into the Allegheny. The cry of "Pond freshet" brought out the entire population of the town, it was a gala occasion. Crowds gathered on the shores to watch. Even here the boatmen were not out of danger. Often a boat struck a rock a few rods above the Oil City bridge, others struck the piers of the bridge itself. In either case the boats were usually rendered into kindling and the oil lost. Oil lost from the overturned boats floated into the eddies below the mouth of Oil Creek and belonged to whoever dipped it up. Oil was so plentiful after one of these disasters people leased land between Oil City and Franklin for the purpose of throwing out booms and taking up the oil as it went downstream. In Nov., 1861 Jacob Jay Vandergrift of Pittsburgh started the bulk oil boat business when he towed two large coal boats loaded with 4,000 empty barrels to Oil City with his steamer, the Red Fox. While delivering the barrels, he bought 5,000 barrels worth of oil, then he had to figure out a way to get all that oil back to Pittsburgh. His solution: he had a contractor build 12 boats, 80 feet long, 14 feet wide and three feet deep, each with a capacity of 400 barrels. With these boats Vandergrift launched a very profitable barge business. These boats were the precursors of today's huge tankers. During the warm summer months, water transportation wasn't feasible - Oil Creek and the Allegheny River were too low. During these months, oil had to be hauled overland. Prior to 1862, the nearest railroad stations to the oil region were those at Corry, Union Mills (now Union City) and Garland, each about 25 miles north of Titusville. Getting oil to these railroad stations was an undertaking of gargantuan proportions. As many as 6,000 teamsters were regularly engaged in hauling oil by horse-drawn wagon. It was reported that as many as 2,000 teams passed over the Franklin Street bridge in Titusville in just one day. It was not uncommon to see a solid line of teams a mile or more in length on the roads leading to Union Mills, Corry and Garland. All this travel was done on roads which were, the say the least, muddy. Oil leaking from the barrels on the wagons mixed with the mud, creating a gooey paste which destroyed the capillary glands and hair of the horses. This meant most of these horses had no hair below the neck. The mud was so thick many wagons dropped into mudholes below their axles, horses sank to their bellies and many of them, falling into the muddy morass, were simply left to smother. Hundreds of horses could bee seen along the banks of Oil Creek. If this happened, the teamster driver simply secured another horse, but in doing so, he lost his place in the line. He therefore had to take his place at the end. If a wagon broke down, the driver dumped the load onto the ground and went on, leaving the oil to be stolen by anyone who thought it valuable enough to be worth taking. In 1862, all this changed with the coming of the railroad. Shortly after Drake's discovery, a group of capitalists headed by Thomas Struthers of Warren, PA. organized and capitalized the Oil Creek Railroad. Its charter authorized this company to construct a railroad from any point along the Philadelphia & Lake Erie Railroad to Titusville, thence along Oil Creek to Oil City and Franklin. In 1862 this company built a line from Corry to Titusville. Corry was selected as the northern terminus in order to connect with both the Philadelphia & Lake Erie and the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad, which also served that community. Within two years the Oil Creek Railroad had also constructed a line from Titusville south along Oil Creek to the Shaffer farm. From the beginning, the Oil Creek Railroad had an overwhelming amount of business. During its first 14 months of existence it carried 430,684 barrels of oil, 459,424 empty barrels, 22,727 tons of merchandise and 59,987 passengers. The Atlantic & Great Western Railroad, having captured a large portion of the oil sent east from Corry, became interested in gaining control of the oil shipped from the southern end of the oil region, at Franklin. Accordingly, it extended a line from Corry to Meadville and thence to Franklin, completing it by March, 1865. The hold of the teamsters on the oil transportation business was also shaken by Samuel Van Syckel, the man who built the first successful oil pipeline from Pithole to Miller Farm on Oil Creek in 1865. This line extended for 5 1/2 miles and utilized two-inch pipe. Capacity of the line was 1,500 barrels per day. A tank farm with the capacity for holding 20,000 barrels of oil was constructed on the Miller farm. Four 10 horsepower engines were used to pipe the oil over the hills between Pithole and Miller farm. Oil from the pipeline was placed into the tanks. Large platforms were built adjacent to the railroad, upon which barrels were filled by means of pipes extending from the tanks. The filled barrels were then rolled onto railroad cars. By the mid-1860s much of the oil drilling activity was centered around Wildcat Hollow and Petroleum Center, an oil town that sprung up in the very center of the oil region. Wildcat Hollow, an almost circular ravine of half bowl facing Oil Creek, was purchased by Frederick Prentice, a resident of New York City, in 1863. Prentice had recently formed the New Jersey Oil Company. His partners were James Bishop, then a resident of New Brunswick, NJ and George Bissell, then a resident of Franklin, PA. This trio together formed the Central Petroleum Company of New York City and began drilling. They took a new approach - they began drilling in previously unknown territory, i.e. Wildcat Hollow. From this is derived a term still used today "wildcatters". Their efforts proved fabulously successful. Nearly 200 wells were drilled in Wildcat Hollow, some so productive the area became a center for early refining activity. At one time seven refineries were located in the Hollow. One of these was the Monitor Oil works which was owned partly by George Stephens. Stephens later moved into Titusville, where he invested in other refineries, lumber mills, stave mills and a barrel factory which he owned jointly with Michael Heisman, father of college football coach John Heisman (1869-1936). The Heisman trophy, given each year to the most outstanding college football player in America, is named after John Heisman. The Central Petroleum Company laid out a town (Petroleum Center) on the lands adjacent to Wildcat Hollow. Petroleum Center reached its peak during the years 1866-1870. It was known for its spectacular oil wells and also for crime - gambling, prostitution, drunkenness and murders. President Ulysses S. Grant visited Petroleum Center by train Sept. 14, 1871. Grant made a speech at the Central House and made stops at Columbia Farm, Tarr Farm, Rouseville and Oil City. This visit proved to be Petroleum Center's swan song. Production declined rapidly after that. Several methods were used to halt the decline of marginal oil wells. Casing was installed in many producing wells to keep water from ruining oil production. The invention of the Roberts torpedo in 1866 enabled producers to remove paraffin deposits from marginal wells. The Roberts torpedo used nitroglycerin to literally explode the unwanted paraffin away. Suction pumps were used to remove natural gas from the wells. These led eventually to the development of the natural gas industry. Rockefeller Seizes the Industry No discussion of oil industry history is complete without mention of John D. Rockefeller. In 1860 Rockefeller, then a young produce merchant from Cleveland, Ohio, visited Titusville to look into the oil business. When he returned home, he reported that he felt the oil business was uncertain from the producing standpoint although the refining aspect of the industry looked promising if a continuing supply of crude oil could be obtained. He bought a small refinery in Cleveland two years later, but in 1865, when he learned of the discovery of oil in the Pithole field, he became assured there would be a good supply of oil for many years. He therefore bought out his partner in the oil business. Within a short time he was making his own barrels, making acids, buying crude directly from the producers and hauling much of his oil with his own horses and wagons. Rockefeller thrived, but he and the other Cleveland producers were hampered by their location. They had to haul oil in from Western Pennsylvania to be processed in Cleveland, then they had to ship it back to the east coast markets by rail. To reduce his transportation costs, Rockefeller in the spring of 1868 approached the Lake Shore Railroad, part of the New York Central system and demanded a rebate on all oil shipped. To gain leverage, he threatened to move his refineries from Cleveland into the oil region if the rebate wasn't granted. The railroad went along and granted a rebate on crude oil and on kerosene transshipped to New York. It should be noted that rebates were common in those days. Rockefeller had simply applied the rebate method to a field where it had never been tried before. It worked. By 1869 Rockefeller's refineries were the largest in the world and he proudly proclaimed, "The oil business is mine." By the early 1870s the oil industry was to say the least unpredictable. Production often exceeded demand, and when railroads and pipelines could not move all the crude being produced, storage tanks filled quickly and eventually prices fell. The market was, in a word, cyclical. The producers tried several times to control production in order to stabilize the market, but they met with little success. The refiners were in an even more precarious position. By 1871 refining capacity was more than double the production of crude. Refiners found themselves bidding against each other to obtain crude in order to keep their refineries operating. Naturally, few refineries operated at full capacity and some were forced to shut down. The largest refiners (most importantly, Rockefeller) and the railroads were especially concerned, and they did something about it. A clandestine organization of an abandoned Pennsylvania corporation, the South Improvement Company, was affected Jan. 18, 1872 when a secret contact and agreement was accepted by the chief officers of the New York Central, Erie and Pennsylvania railroads and by 13 of the largest refiners from Cleveland, Pittsburgh and New York. When news of this secret agreement got out, 20 of the 25 independent refiners in Cleveland sold out to the Rockefeller group (Standard Oil of Ohio) in less than six weeks. The South Improvement Company agreement split oil freight on a percentage basis among the three railroads. These roads agreed to double rates on crude oil and refined oil from the oil regions to the refining centers, promised members of the Company a maximum rebate of 50 percent, agreed to furnish waybills on all oil shipped over their lines to members of the Company and introduced the "drawback", whereby members of the South Improvement Company received rebates on oil shipped by their competitors. The plot was revealed by accident Feb. 25, 1872, when an employee of the Jamestown & Franklin Division of the Lake Shore Railroad raised the rates prematurely. The independent refiners and producers were furious. They faced ruin and the loss of huge investments. Mass meetings were held at Tidioute, Erie and Shamburg. On Feb. 27, 1872, 3,000 furious oilmen met at Titusville's Parshall Opera House to give battle to the combination. On March 1, under the leadership of Captain William Hasson, John Archbold and Jacob J. Vandergrift, a Petroleum Producers Association was formed, pledges were made that no wells would be drilled for 60 days and crude was to be sold only to those refiners not connected with the South Improvement Company. New York and Baltimore producers soon joined with the Pennsylvania independents. They contacted the state legislature and on April 2, 1872 the charter of the South Improvement Company was revoked by the state. The victory of the independents seemed complete, but the very next month Rockefeller and his aides formed a new association called the Petroleum Refiners Association, of which he was president. This new unincorporated association was open to any and all refiners who would place themselves under the control of a central board, the board would handle crude oil purchases, allocate refining quotas, fix prices and negotiate freight rates with the railroads. The independent producers, skeptical of the plan and alarmed because of increasing production from Armstrong, Butler and Clarion counties in Pennsylvania, formed the Petroleum Producers Agency to buy and, if necessary, hold the crude in storage at $5 a barrel, cut production and build refineries if required. Rockefeller recognized this new danger and offered to purchase their crude if production could be controlled. The producers signed with Rockefeller, but drilling and new production in the new fields ran rampant. The new joint agreement was eventually canceled. Through these two failures, Rockefeller learned that loose combinations could not properly control either production or refining. He therefore took more positive steps. First, he secured from the Erie Railroad both barreling and shipping facilities in New Jersey, thus enabling him to control the export end of the market. Next, he persuaded the railroads handling the oil traffic to equalize the rates on crude oil and kerosene. Then, he hired Daniel O'Day to head his American Transfer Company and to building pipelines from the Clarion oil field to Emlenton, where rail connection could be made to Franklin and Cleveland. In 1874 and in 1879 he bought the interests of the largest independent pipelines and by 1883 he organized the National Transit Company. Takeover of refineries began in 1874. Refiners not willing to sell out to him were drastically undersold, found themselves without barrels, had delays in securing tank cars and learned that part of the freight rates they paid were rebated to others. It did not take long for Standard Oil to buy 20 of the 21 refineries in Pittsburgh, 10 of the 12 in Philadelphia and all of them in the actual oil regions. By July, 1878, at the age of 38, Rockefeller controlled 97 percent of all the pipelines and refineries in the country. Not all the independent Pennsylvania oilmen stood idly by while Standard Oil moved to control every phase of their business. They were aided by the discovery of oil in a new field, the Bradford (Pa.) field. This proved to be a prolific area. Bradford, in McKean County (about 100 miles north and east of Oil Creek), was a sleepy village of 500 people at the beginning of 1875. By year's end wildcatters had penetrated the oil bearing sands around the town and a new rush was on. Train loads of oilmen from "the lower country" crowded the streets and overran the hotels. Main Street at night looked like a frontier town. Saloons and dance halls were thronged and gambling dens ran without interference. By 1878 Bradford had a population of 4,000. Over 1,000 letters were received daily at the post office. The money order business amounted to $2,000 a week. Railroad traffic was tremendous. At times there were as many as 250 loaded cars standing in the yards. With 7,000 producing wells in the region averaging 65,000 barrels a day, Bradford was the oil metropolis of the world in 1880. By then its population exceeded 11,000 and its post office was the third largest in Pennsylvania. All this new production gave the independent oilmen a tool with which to combat Standard Oil. In 1878 three of Standard's foes, Byron Benson, David K. McKelvy and Major Robert E. Hopkins, formed the Tidewater Pipe Company. Financed by many of the largest regional producers, this firm constructed a pipeline from Coryville in the Bradford field to Williamsport. From there the Reading Railroad took the oil to the sea. The line was started in Nov., 1878 and completed the following spring. It was a godsend to the few independent refineries still in operation in New York and Philadelphia. They were glad to get some relief from Standard Oil pressure and control. The cost of getting a barrel of oil to seaboard via this pipe was 17 cents, compared with the previous price of 85 cents. The heyday of railroad transportation of oil was ending. The Tidewater independent pipeline was a real threat to Rockefeller's interests, and he reacted in his characteristic manner - he bought out all the refineries that had promised to take oil from Tidewater's pipes, with one exception. Even this did not kill Tidewater, for that firm simply went out and built plants of its own at Philadelphia and Bayonne, N.J. Finding no other means of putting the new firm out of business Rockefeller purchased one-third of Tidewater's stock and by 1883 Standard Oil and Tidewater ended their battles and became allies. The independents fought back again. Lewis Emery, Jr., of Bradford, an implacable foe of Standard Oil, organized the United States Pipeline Company and by July, 1893 had a crude line extending eastward as well as a refined line from the region's producers. In January, 1895 the producers and refiners who had suffered much from Standard Oil met at Butler, Pa. and formed the Pure Oil Company. Five years later Pure Oil merged with Emery's United States Pipeline Company. By 1901, their pipeline had reached Philadelphia and the seaboard. The struggle of the independent oilmen was long and difficult, but proof of how well they built is evidenced by the fact the Tidewater Oil Company (now known as Getty Oil Company) and Pure Oil (now a division of Union Oil Company) are still important factors in the oil business. The Sherman Antitrust Act was passed July 2, 1890. In 1911 the Supreme Court ruled that Standard Oil had violated this act and directed that the corporation dissolve itself within six months. As a result, Standard Oil was broken up into 34 separate companies. Petroleum Centre became the hub of oil activity in the 1860s, as well as oil fields at Tarr Farm, Pioneer and Miller Farm. By 1875, the oil wells began to dry up and the towns along Oil Creek began to die. Not much is left of the early oil boom. There is little in the natural beauty of Petroleum Centre to suggest the turbulence of its heyday. The wooded hills of Oil Creek Gorge look almost as they did before the boom. A few wells are still active in the park, pulling the last bits of oil and natural gas from the earth which nature laid down hundreds of thousands of years ago.

Certificate Vignette

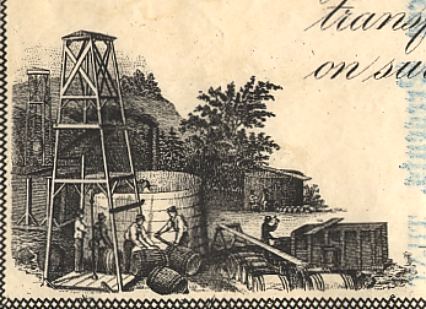

Certificate Vignette