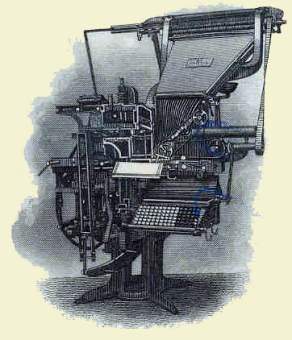

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Mergenthaler Linotype Company issued in 1896. This historic document was printed by the Homer Lee Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of a linotype. This item is hand signed by the Company's President ( Philip T. Dodge ) and its Treasurer and is over 120 years old.

Certificate Vignette In 1889, The Linotype Company, a British offshoot of the firm was formed by Joseph Lawrence, publisher of The Railway Magazine. In 1899, a new factory in Broadheath, Altrincham was opened. In 1903, the British company merged with Machinery Trust to form Linotype and Machinery Ltd. Mergenthaler Linotype dominated the printing industry through the twentieth century. The machines were so well designed, major parts remained virtually unchanged for nearly a hundred years. The company, as so many in the printing industry, endured a complex post-war history, during which printing technology went through two revolutions -- first moving to phototypesetting, then to digital. During the 1950s, the Davidson Corporation, which manufactured a series of small offset presses, was a subsidiary of Linotype. This was later sold to American Type Founders and operated under the name ATF-Davidson. Through a series of mergers and reorganizations, the business of Mergenthaler Linotype Company ultimately vested in Linotype-Hell AG, a German company. In April 1997, Linotype-Hell AG was acquired by Heidelberger Druckmaschinen AG. The following month certain divisions of Linotype-Hell AG were spun off into new companies, one of which was Linotype Library GmbH with headquarters at Bad Homburg vor der Höhe. This new company was responsible solely for the acquisition, creation and distribution of digital fonts and related software. This spin-off effectively divorced the company's font software business from the older typesetting business which was retained by Heidelberg. In 2005, Linotype Library GmbH shortened its name to Linotype GmbH, and in 2007, Linotype GmbH was acquired by Monotype Imaging Holdings, Inc., the parent of Monotype Imaging, Inc. and others. Typefaces The typefaces in the Linotype type library are the artwork of some of the most famous typeface designers of the 20th Century. The library contains such famous trademarked typefaces as Palatino and Optima by Hermann Zapf; Frutiger, Avenir and Univers by Adrian Frutiger; and Helvetica by Max Miedinger and Eduard Hoffman. Linotype GmbH frequently brings out new designs from both established and new type designers. Linotype has also introduced FontExplorer X for Mac OS X. It is a well reviewed font manager that allows users to browse and purchase new fonts within the program -- a business model similar to that used by iTunes and the iTunes Store. Ottmar Merganthaler was born on the 11th of May, 1854 in the tiny German village of Hachel. Arriving in Baltimore in 1872, Merganthaler took a job in the Hahn Company machine shop, which produced models for the U.S. Patent office, it was here that he met James O. Clephane. Clephane was a Supreme Court reporter and former secretary to William H. Seward who was part of President Lincoln's cabinet during the Civil War. Clephane was an early developer of shorthand writing systems and a proponent of the first typewriters. Seeking a way to quickly and efficiently reproduce his typewritten documents he recruited Merganthaler. After several years of painstaking work Merganthaler developed a machine which combined the tasks of casting and setting type. First patented in 1884 and used commercially in 1886 at the New York Tribune, Merganthaler's invention became known as the Linotype. The machine had long vertical parallel bars, each bearing a complete alphabet of metal type or dies, and a fingerboard by which the selected letters for a line, one on each bar, could be brought into alignment and impressed in papier-mache, thus producing one after another justified matrix lines; the papier-mache matrices thus produced being transferred to a second machine from which the slugs or linotypes were cast, one at a time, line after line. In October, 1891, a new company, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company of New York, was formed and succeeded to the holdings of the older companies. The Mergenthaler Printing Company and the National Typographic Company had expended upward of two million dollars and had exhausted their capital. The new company was provided with a cash capital of only $374,000, and it was with this limited capital that Mr. Dodge was required to reestablish and carry on the business. The first dividend was not paid until August, 1894. The Linotype Company had Mr. Philip T. Dodge, of Washington, as president and general manager. Mr. Dodge was a young patent attorney of Washington, and had prepared and solicited the patents on the Linotype from a very early period. He took hold of the business as president and general manager in November, 1891. The There was no ownership of real estate. The tool equipment was limited and imperfect, and the factory consisted of a small leased building. The machine at that time was far from perfect and worked in a more or less unsatisfactory fashion. He had the opposition of those who feared that their trade would be ruined, and of those who were skeptical in view of the vast sums that had been lost in the typesetting machine business. Linotype machines revolutionized the printing industry in the late 19th century. Newspapers and print shops throughout the world were quick to adopt Merganthaler's invention. The increases in efficiency brought about by the Linotype machine greatly reduced the cost of printed material making things like books, newspapers and magazines available to a much larger populace. Continuous improvements have been made to the Linotype throughout the years as evidenced by the over 1000 linotype related patents taken out. Linotypes were a mainstay of the printing industry through the better part of the 20th century and are still in use in some print shops today. The early 1890s was a period when newspaper, book, and magazine printers tried out the new composing machines entering the market. Various contests and demonstrations were held, with the Linotype usually producing the best records. Organized labor initially had qualms about a machine that they feared would put its printers out of work, but by 1900 their objections had largely subsided as union printers had taken control of the machines and the demand for printed material had increased. Both before and after Mergenthaler's death, the Mergenthaler company defended its patents against interference and infringement by competing machines. It also bought out a competitor in 1895 to obtain patent rights for the crucial double-wedge spaceband used in justifying the lines of type. The Linotype thus "held the field" until after the inventor's principal patents expired and the competing Intertype was introduced in 1913. Linotypes were extensively improved over the years as installation proceeded in a majority of the nation's printing plants. The hot-type systems using them began their decline after World War II. Intense labor problems and the adoption of offset printing and cold-type photocomposition methods (and later computers) coincided with publishers' desires for lower costs. The Mergenthaler company ended U.S. production in 1971 after building nearly 90,000 Linotypes. Probably a few thousand were still in use in the United States in the early 1990s. The Merganthaler Linotype Company continued until 1987 when a company from Germany acquired it and its name was changed to Linotype AG. The The Mergenthaler Linotype Company arose during the nineteenth-century out of a number of mergers and takeovers of related businesses. The company developed and manufactured the first truly modern, functional linotype machine. Originally invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler in 1884, the Linotype machine cast solid lines of type with matrices, eliminating the need for stocks of metal type, and replaced manual line composition with keyboard composition. On November 25, 1891, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company of New Jersey assumed all American rights of the National Typographic Company and its licensee, the Mergenthaler Printing Company of New York. Philip T. Dodge, formerly the patent attorney for Remington, was elected president. Early manufacture and sale of Linotype machines grew dramatically: from ninety-seven machines during the ten months of the first fiscal year to 690 by 1894. Within three years, the company boasted one hundred daily newspapers as customers. In December 1895, the company reincorporated as the Mergenthaler Linotype Company of New York, and assumed all the properties and franchises of the previous Mergenthaler Company. Despite its shared name, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company emerged as a distinct corporate entity from inventor Ottmar Mergenthaler. During its early years, the Mergenthaler Company aggressively defended itself against patent infringements, but by 1912, most of the original Linotype patents had expired. In 1913, the Intertype Typesetting Machine Company (formerly the International Typesetting Machine Company and later the Intertype Corporation) developed and marketed a similar machine, known simply as the Intertype. In fact, many of the parts of the two machines were interchangeable. By 1954, an estimated 98,000 Linotype machines had been produced worldwide. Eventually, cold type processes, which reproduced letters without using hot, i.e. metal type, rendered the Linotype obsolete. Domestic manufacture of Linotype machines ended in 1968. History from Linotype Organization and OldCompany.com.

Certificate Vignette