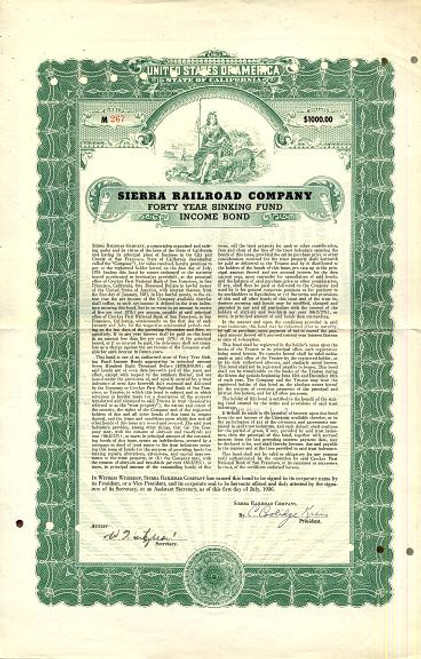

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Western Pacific Railroad Company issued no later than 1952. This historic document was printed by the Security Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of an allegorical man and woman sitting on both sides of Western Pacific train no. 901. The train has the compny's logo on the front. This item has the printed signatures of the company's president and secretary and is over 51 years old.

Certificate Vignette

Company logo Fifty Candles for Western Pacific by G.H. Kneiss as published in the Western Pacific's March 1953 company magazine Tuesday, March 3, 1903, was just another rainy day to most San Franciscans. There wasn't much excitement. Carrie Nation, armed with axe and Bible, smashed some bottled goods and glassware in a Montgomery Street saloon and was hustled off to jail. To jail likewise went Miss Flo Russell, a young lady whose crime lay in exposing an ankle and bit of petticoat while lifting her skirts high enough to clear the muddy pavement, and to jail in Marin County, across the Bay, went one George Gow, who illegally failed to bring his automobile to a dead stop when a horse-drawn vehicle approached within 300 feet. Over in Corea (as it then was spelled), San Franciscans learned from their newspapers, fighting went on along the Yalu River between the Russians and the Japanese, and at Harvard Professor Hollis, chairman of the Athletic Committee, said that football aroused only the worst impulses and should be abolished. Up in Sacramento Governor Pardee signed a bill making the Golden Poppy the state flower of California. No, not too much excitement, but even so readers of the San Francisco Chronicle next day reached. page 14 before they learned that eleven men had sat down around a table in the Safe Deposit Building on California Street and organized a new transcontinental railroad to be named the Western Pacific. It was to run from the city of San Francisco eastward through the canyons of the Feather River and Beckwourth Pass and on to Salt Lake City. By branch lines it was also to serve San Jose, Alameda, Berkeley, Richmond, Fresno, Chico and Prattville. Walter J. Bartnett, San Francisco, lawyer and promoter, had subscribed to 14,900 of the 15,000 shares of capital stock but behind him, speculation went, were probably the Goulds, the Vanderbilts, Jim Hill or David Moffat. Perhaps the reason that the Chronicle put its writeup back on page 14 along with the truss ads and the electric belts was that the story was not exactly new, Men had talked about a railroad through the Feather River Canyon for a long time, particularly one named Arthur W. Keddie. KEDDIE'S DREAM Keddie had come to California in the early sixties - a young Scottish lad, trained as a surveyor. By that time the goId diggers that had briefly overrun the Feather River country following Bidwell's celebrated discovery on July 4, 1848, had departed with their pokes and six-shooters. Barkeeps and dance hall gals had followed them. The many-pronged turbulent river which Arguello had named Rio de las Plumas because of countless floating feathers from moulting wild pigeons, flowed in solitude through its deep gorges. One of thefirst professional jobs that came Keddie's way after he had hung out his shingle at Quincy, county seat of Plumas County, was that of exploring the North Fork of the Feather for the newly-organ ized OroviIIe and Beckwourth Pass Wagon Road Company. Beckwourth Pass, for unknown ages a great Indian thoroughfare, had been discovered to civilization by Jim Beckwourth, a mulatto scout, in 1850. A Sierra crossing more than 2,000 feet below the elevation of Donner Pass, it had become popular for covered wagon trains. Keddie made his canyon reconnaissance in the dead of winter but the snows he encountered were surprisingly light. Furthermore, he found a route with grades too easy to waste on a wagon road. Back to Quincy he went with a thrill and a dream in his heart -the thrill of having discovered what he felt sure would prove to be the best route for a transcontinental railway and the dream of having part in building it. The young surveyor managed to interest several important men in his idea: Asbury Harpending of diamond hoax fame, Civil War General William Rosecrans, Creed Hammond and others.Some of them were sincerely interested in railroad building. Harpending, for one, was convinced that the Central Pacific had chosen a most inferior route over the mountains and would be easy competition. As the Quincy Union put it: "The Central Pacific have long since understood they must content themselves with the summer trade of Virginia City and Carson. The Feather River Railroad will be the road across the continent." But others of the associates were looking only at the speculative possibilities when coupled with their own political influence. The Oroville and Virginia City Railroad Company was formed in April, 1867. Capital stock sales were authorized up to five million dollars, but a negligible amount was sold. Where upon some of Keddie's new associates railroaded a most amazing bill through the California Legislature and induced Governor Haight to sign it. This new law was entitled "An Act Authorizing the Board of Supervisors of Plumas County to take and Subscribe to the Capital Stock of the Oroville and Virginia City Railroad Corn- pany." Actually, it not only authorized them, it specified that said Supervisors could be fined, removed from office, and sued for damages if they didn't do so! This may have been good politics but it was deplorable public relations. Enthusiasm for the railroad in Plumas County cooled while indignation boiled and the Supervisors resigned en masse. A legal battle finally repealed the obnoxious statute. General Rosecrans tried to induce the Union Pacific to take over the 0. & V. C. project as its California connection and thus by-pass the Central Pacific with its already critical snow problems. His old comrade in arms, General G. M. Dodge, actually left his U. P. construction camp and came out to consider the offer. He liked what he saw but the Central Pacific end-of-track was miles into the Nevada sagebrush by then and, although the Union Pacific was authorized by congress to build to the California line, it had to stop wherever it met the C. P. Keddie started construction on the 0. & V. C. near Oroville in the spring of '69. A gang of thirty Chinese men was put to grading between Thompson Flat and Morris Ravine. Shortly afterward Congress was asked to help with a land grant of 641,200 acres. But the whole thing blew up. The builders of the Central Pacific were adept at "pressure" and they put plenty of it on Harpending to ditch the scheme. And one of them,C.P. Huntington, laughed Keddie out of his office with the remark "no man will ever be fool enough to build a railroad through the Feather River Canyon." Arthur Keddie had to put his dream in mothballs but he did not forget it. The seventies and the eighties passed. The close of the latter decade found the Union Pacific, less than entirely happy with its western connection, again considering its own line to San Francisco. Out in the field was Virgil G. Bogue, U. P. chief engineer, running trial surveys over the Sierra. One was down the Pit River, one through Susanville and along Deer Creek, several through Beckwourth Pass and down the Feather. Bogue rather favored the Deer Creek route despite some 80 miles of 4 per cent grade, but Jay Gould gained control of the Union Pacific about that time, and the plans for a San Francisco extension were abandoned. THE SAN FRANCISCO & GREAT SALT LAKE This was bad news to California shippers and merchants who had hoped for some relief from the Central Pacific monopoly which skillfully adjusted rates to the maximum figures which would allow its customers to remain in business. A group of them got together and determined to build the Union Pacific connection themselves. They incorporated the San Francisco and Great Salt Lake Railroad Company and hired Bogue's assistant, W. H. Kennedy. If he could locate a practicable route, one which was not too expensive, they felt it should be possible to find Eastern capitalists who would finance the undertaking. Kennedy was, of course, familiar with the surveys made by Union Pacific but believed he might find an even better line. In Quincy he called at the County Surveyor's office for a map of Plumas Country; the County Surveyor was Arthur Keddie, and the two men found a lot to talk about. Keddie told the engineer of the low pass he had found near Spring Garden Ranch between the Middle Fork of the Feather and Spanish Creek, a tributary of the North Fork. As the Middle Fork Canyon became impossibly steep below this point and the North Fork was almost as bad above it, this low divide offered a means of utilizing the best parts of both canyons. Crossing the Sierra summit at Beckwourth Pass, thence descending the upper reaches of the Middle Fork and cutting over to the North Fork at Spring Garden, as Keddie had suggested, to reach the Sacramento Valley at Oroville, Kennedy completed his survey late in 1892. It was a good line, with a ruling grade of 1 1/3 per cent, and as he filed his maps in the various county court houses, they established under the existing laws, a five-year option on the route in the name of the San Francisco and Great Salt Lake Railroad Company. With these rights and Kennedy's estimate of $35 million to build the railroad, the San Franciscans journeyed to New York City, the lair of capital. But everywhere the S.F.&G.S.L. Promoters called, they found Collis P. Huntington had been before them. Why spend $35 million to compete with him, the wily old man had asked each likely angel, he'd be gladto let them have the Central Pacific, monopoly and all, for a good deal less and be glad to get it off his hands. No one called his bluff and the San Francisco and Great Salt Lake Railroad Company joined the other punctured bubbles. HARRIMAN VS. GOULD When Jay Gould had acquired control of the Denver and Rio Grande properties, he had seriously considered extending them to the Pacific Coast. The Union Pacific, however, control of which he no longer owned, had induced him not to. Both systems interchanged their westbound traffic with the Central Pacific at Ogden and in return the latter divided its eastbound loads equitably between them. But when E. H. Harriman and his supporters, after acquiring the Union Pacific, picked up control of the Southern Pacific System after C. P. Huntington died in 1900, they closed the Overland Gateway to the rival Rio Grande. George Gould, Jay's eldest son, had succeeded to the 11,000-mile rail empire by then. It was his ambition to have his own rails from coast to coast.They already stretched from Buffalo to Ogden, he had definite plans to reach Baltimore, and he had hoped to acquire the Central Pacific himself. Now, bottled up in Utah by Harriman, he decided to build a new road to San Francisco. Virgil Bogue had become George Gould's consulting engineer and recall-ing his surveys for the Union Pacific in the '80's, recommended Beckwourth Pass and the Feather River route. Remembering also an unhappy experience he had once had in locating any other road, only to find the whole route plastered with mining claims of dubious mineral value but through which rights of way must be negotiated, he advised Gould to form a "mining company" first. Accordingly the North California Mining Company was organized and soon nearly 6OO placer claims were staked out, blanketing the entire proposed route across the mountains. Gould turned the job over to the Denver and Rio Grande and its president, E. T. Jeffery, sent a field party under H. H.Yard west to locate the line. It was all top secret. The transit men and stake artists were forbidden even to let their wives know where they were. Letters could only be exchanged through the Denver office of the railroad. Two California corporations, the Butte and Plumas Railway and the Indian Valley Railway, were set up to be the figureheads. It was, however, more than a bit difficult to keep anything concerned with a railroad through the Feather River Canyon secret from Arthur Keddie. That was a subject he kept up with. Furthermore, he had another railroad scheme on the fire himself. He had formed an alliance with one Walter J. Bartnett who, with his associates, had built a short line, the Alameda and San Joaquin Railroad only a few years before from Stockton southwest to the Tesla coal mines. The mines had not come up to expectations and Bartnett, who was an exceedingly high powered promoter, had conceived the ambitious plan of extending his 36-mile railroad east to Salt Lake City and west to San Francisco and then selling it to the Goulds. Bartnett and Keddie incorporated the Stockton and Beckwith (sic) Pass Railroad on December 1, 1902. Location was amazingly fast and simple. For Keddie merely put some stooge "survey parties" out in the canyon and as they haphazardly staked out each ten miles of "line," he made a copy of the corresponding map Kennedy had filed in 1892 and, by registeri ng these in the county seats, won an incontestable five-year franchise. Walter Bartnett then journeyed to New York with Keddie's franchise in his pocket, convinced George Gould that it could not be ignored. Bartnett and Gould signed an agreement on February 6, 1903, which provided for the formation of a new company to take over the various corporations which each had previously organized and to build and equip the railroad. Less than a month later and pursuant to this pact, the meeting in the Safe Deposit Building was called to order. THE WESTERN PACIFIC IS BORN The Western Pacific Railway Company was thus organized on March 3, 1903. Articles of Incorporation were filed with the County Clerk the same day. But when Bartnett's clerk appeared next day at the Secretary of State's office in Sacramento, the first of many roadblocks thrown up by the Southern Pacific became apparent. For the pioneer railroad between Sacramento and Oakland, completed way back in 1869, had also been named Western Pacific and the S.P., which had taken it over, still claimed all rights to the name. Bartnett threatened mandamus proceedings and the S.P. withdrew its objections. The Western Pacific Railway Company was thereupon incorporated, on March 6, 1903. George Gould still remained completely out of the picture and denied all connection with the project. Although he financed the new surveying parties that were immediately sent out to make the final location, he was forced, in the interests of this secrecy, to keep the Rio Grande engineers in the field as well. The absurd result was two hostile groups struggling to outwit each other and often on the point of exchanging pot shots, though both were actually on the same payroll. Virgil Bogue was finally dispatched by Gould to choose the best of the routes surveyed. One night, as he sat in his field tent pondering the old Kennedy line with its grade of 1 1/3 per cent which the Western Pacific engineers had accepted from Keddie, he noted from the profiles that between Oroville and Beckwourth Pass there was only a difference in elevation of 50 feet per mile. This suggested to him the idea of a uniform one percent grade. Rapid investigation proved this feasible, and without climbing too high above the river. Elated, Bogue wired E. T. Jeffery and with equal enthusiasm the D&RG president answered that if a one per cent grade railroad between San Francisco and Utah could belocated, money to build it was available regardless of the cost. Shortly thereafter General G. M. Dodge wrote to one of Bogue's associates as follows: "I am glad to see that you are out there on the Western Pacific. That line is almost exactly the line I run (sic) south of Salt Lake, thence down the Humboldt, across the Beckwourth Pass, and down the Feather, but you have a better grade than I got. That is the line the Union Pacific would have built if it had not been for the progress of the Central Pacific east." Rumors were still thick as to who was behind the Western Pacific. Some thought the Burlington interests. Others picked "Jim" Hill of the Great Northern or David Moffat, the Colorado capitalist. Most felt positive that Gould was behind the road despite his still positive denials. There was a story current that Harriman and Ripley (of the Santa Fe) had together offered him two million plus all he had spent so far to give up the project. It was not until the spring of 1905 that Gould publicly announced his paternity of the Western Pacific and appointed President Jeffery of the Rio Grande to head the new road as well. Bartnett, who had been president, became vice-president. Contracts for construction were signed late the same year, although the line was not completely located nor the rights of way all secured. The Southern Pacific naturally interposed every possible legal and physical obstacle, but although it possessed immense political power and a formidable bag of tricks, the Western Pacific promoters usually managed to come out on top. WAR ON THE WATERFRONT The biggest row was that involving the WP ferry terminal on San Francisco Bay. A little historical background is necessary here. Oakland was an unnamed part of the Peralta rancho in 1851, when lawyer Horace Carpentier and two associates made themselves at home on the oak-studded meadows around what is now lower Broadway and started selling lots. Don Vicente Peralta rode around with the sheriff when his cattle began to disappear, but Carpentier glibly talked him into a lease of the land on which he had squatted and then proceeded to incorporate it as the City of Oakland. His hand-picked trustees gladly "sold" him the entire 10,000 acre waterfront between high tide and the ship channel for five dollars plus two per cent of any wharfage fees he might collect. Carpentier then took office as mayor. In 1868 when Central Pacific interests sought a terminal on the Bay at Oakland, Carpentier made a nice deal with its management. The Oakland Waterfront Companywas incorporated for $5,000,000 by both parties. Carpentier became its President and conveyed "all the waterfront of the City of Oakland" to the new corporation. Through this succession of events the Southern Pacific had maintained a stranglehold on the Oakland waterfront for half a century, although the city had several times attempted to invalidate the title. Obviously the S.P. was fully confident that it would have but little difficulty in isolating the Western Pacific from a practical outlet on the Bay. The Santa Fe, only a few years before, had built its ferry slip way up at Point Richmond rather than attempt to crack the S.P. stronghold. Bartnett, after a hard struggle against the older railroad's influence, did secure a small site on the mudflats of the Oakland Estuary. It would have made a miserably cramped ferry terminal but, from all appearances, the WP promoters had concluded it was the best they could do. Harriman's forces sneered and relaxed. Gould's were just beginning. Every move was carefully rehearsed and logistics figured to the last detail. As the Oakland tidelands had gradually been filled in, the Government had extended the banks of San Antonio Estuary with rock quays called "training walls" in order to prevent silt from washing into the Oakland inner harbor channel. A dredger was often necessary to prevent the formation of a bar at the entrance of the channel. This dredger became the Trojan horse of the Gould attack. On the night of January 5, 1906, the Western Pacific forces under Bartnett struck. With 200 workmen and 30 guards armed with carbines and sawed-off shotguns, he used the dredging company as a front, and seizing the north training wall, began feverishly to lay a rough track. Most of the guards took up positions at the shore end of the U. S. training wall and maintained them night and day. Laborers snatched their sleep in shelter tents on the wave-washed rocks and the WP commissary department fed them. Scows rushed more rails and ties across the Bay to the end of the wall. Soon there was a mile of track on top of the rock wall. Of course the Southern Pacific did not quietly accept this outrageous trespassing on domains it had held undisputed for more than half a century. Its legal department, fairly in convulsions, was whipping out the necessary papers for immediate appeal to the law. This was exactly what Bartnett had told Gould would happen and exactly what they both desired. For the courts, as Bartnett had felt sure they would, held that the Southern Pacific title to the waterfronts had not progressed westward with the shoreline as the tidelands and marshes had been filled in, but was valid only to the low tide line of 1852. The S.P.'s "waterfront" therefore was by now well inland, and the new marginal land surrounding it was the property of the city. Years later, when the firstWP passenger train reached Oakland, Mayor Frank K. Mott in his speech of welcome said: "The advent of the Western Pacific Railway is epochal. It is of peculiar interest to Oakland, for this system's coming made it possible for Oakland to recover control and possession of its magnificent waterfront. This may well be placed first in the order of benefits which will accrue to the city, as well as to the Bay region and the entire state." CONSTRUCTION WAS NOT EASY Construction camps had been established by the contractors at points all along the line undersupervision of Company division engineers. Some were accessible by rail and most of the others by wagon road. But, for much of the distance through the rugged Feather River Canyon, not even a foot path was handy to the route. Indeed the surveyors had often hung suspended by cables over cliffs in order to set their line stakes. So it was necessary first to blaze a trail and set up small camps supplied by pack mules,then use these as bases for building a wagon road over which supplies and equipment for building the railroad could be hauled. It was slow, and often dangerous. At Cromberg it was necessary to cross the swirling river on a jittery rope bridge and here eleven men were lost working on the cliffs or trying to cross the stream. They were tough men too, mostly lumberjacks and hard-rock miners. Where Grizzly Creek drops into the Feather, the field parties were forced to resort to rafts in order to by-pass the sheer granite cliffs. Over at the Utah end crossing the salt beds was a nightmare due to excessive temperature extremes and the killing glare which often blinded men aftera few hours work. It was difficult to hold men under such conditions while more pleasant work was plentiful and turnover was terrific. Bogue actually had detectives infiltrated through some of the gangs under the suspicion that some outside agency must be stirring up trouble and inducing the men to quit, but no evidence of this was ever found. On the other hand the S.P. superintendent at Ogden wrote plaintively that the Western Pacific was stealing all his track men and that it wasn't very neighborly. T. J. Wyche, the WP engineer, replied that all his assistants had positive instructions on this point and wouldn't think of taking S.P. men. A few days later a Greek labor agent reported that the next batch of track men he would deliver would have to wait until they could get their time checks from the S.P.! Drunkenness was a problem too, one which Bogue finally solved by buying up all the saloon licenses handy to the job. After the depression of 1907 set in, there were plenty of men available-and at lower wages. Had it not been for this unexpected break all of the contractors would probably have gone bankrupt, since the work proved considerably more costly than they had figured. In particular, the long tunnels at Spring Garden between the canyons of the North and Middle Forks, Chilcoot at Beckwourth Pass, and at Niles Canyon not far east of Oakland, ran into unexpected delays and costs. Original plans had called for Western Pacific to be ready for business by September 1, 1908, and when it became more and more evident that this date could not be met, President Jeffery felt mounting concern. "It is really a very serious situation to contemplate," he wrote Bogue in January 1907, "and the key is the completion of the long tunnels. The rest of the road we can build and get in running order, and we can have our terminal facilities at San Francisco and Oakland and our floating plant in San Francisco Bay all ready by or before September 1 (1908)," It was in March, 1907, when one of the worst storms in the history of California struck and the resulting floods completely tied up construction. Little damage was done to the half-finished Western Pacific - in fact the storm effectively demonstrated the wisdom of its location and Bogue wrote Jeffery that if they had been building the 1 1/3 per cent grade originallychosen, their prospects would have been grim. But it was impossible to deliver materials to the job. Flood conditions were so bad that S.P. trains from Sacramento to Oakland were operating by way of Fresno. With these and other delays it was not surprising for Jeffery to write, "I long for the day when we can have the railroad in operation and I can see the fruition of my hopes and plans since 1892. Sixteen years is a long time to contemplate, lay plans for and patiently work toward the accomplishment of an enterprise; but this is what I have endured to date, and must endure for fifteen or sixteen months more." But the rail laying which had started with the driving of the first spike at 3rd and Union streets in Oakland on January 2, 1906, proceeded eventually to the driving of the last. On November 1, 1909, the track gangs from east and west met on the steel bridge across Spanish Creek near Keddie and foreman Leonardo di Tomasso drove the final spike. In contrast to the gold spike ceremonies on the first overland railway just forty years before, no decorated engines met head to head before a cheering crowd; no magnums of champagne were broached. The only spectators were a pair of local women and their little girls. ENGINES AND TERMINALS Surprisingly enough, President Jeffery had first favored equipping the Western Pacific with small locomotives of the vintage of 1888. These had given good service on the Rio Grande and were more economical than the heavier engines it had since acquired. The engines Jeffery favored were the D&RG class 106, a ten-wheel passenger locomotive with a tractive effort of 18,000 pounds, and Class 113 for freight, a consolidation with 25,000 pounds tractive effort. Bogue at first appeared to fall in with Jeffery's ideas, but raised one doubt after another as to the wisdom of ordering these little old-fashioned engines. Finally he secured blue prints of the motive power used by the Southern Pacific on the Ogden Route and sent them on to Jeffery in New York with his final comment on the 106 and 113 class: "To place these locomotives on the road, hauling trains in competition with the Southern Pacific, would probably prove to be a mistake." Jeffery was convinced and comparable motive power was ordered: 65 consolidation freight engines with 43,300 pounds tractive effort, 35 ten-wheel passenger locomotives with a tractive effort of 29,100 pounds and 12 switchers. The first twenty freight engines were built by Baldwin, the rest by the American Locomotive Company. They were a lot bigger than the 1888 models although they would appear tiny in comparison with those which would follow while they were still in service. The work horses of the Western Pacific for several decades, they were excellent machines. Yards and terminals for the new railroad had been most carefully designed. Traffic estimates had been prepared from local statistics, S.P. annual reports, etc., and diagrams prepared of expected east and westbound tonnage of various classes. Train mile costs were estimated, on the basis of 1,000-ton 30-car trains without helper service, at $2.25 on the 1 per cent grade as against 1500-ton 45-car trains with helpers at $3.58 plus 36 cents a mile to return light engines. On the basis of such studies Wendover had been selected as the first subdivision point west of Salt Lake City although it was without water. Shafter, 40 miles further east, had plenty of water, better living conditions and was an interchange point with the Nevada Northern. However, Wendover sat at the foot of 33 miles of 1 per cent grade and the selection of Shafter as a subdivision point would have sacrificed tonnage for speed in order to avoid overtime, as well as failure to utilize the 100 miles of nearly level track east of Wendover for maximum tonnage. Bogue estimated annual savings of $100,000 by picking Wendover against Shafter. Each division point had been made the subject of a similar careful study as to location and design. At Oroville, the old gold workings governed the layout and at Portola mountains and river were important factors. Winnemucca was the dividing terminal between coal and oil burning engines and here the Humboldt River influenced its site.Oakland, in particular, had required painstaking analysis as the engine terminal property was constricted and lay between two S.P. Grade crossings. Bogue and his assistants had done their work well. Rates of pay at the opening shed light on the passage of time. Locomotive engineers drew $4.25 per ten- hour day; firemen, $2.75. Conductors were paid by the month, $125 and no overtime. Brakemen got $86.25. In the office, a chief clerk found eleven twenty-dollar gold pieces and a five in his pay envelope; the stenographers $60 or even $75 if they were extra competent. The Western Pacific was now, operative but far from finished. From San Francisco to Salt Lake City it stretched 927 miles, 150 miles longer than the competitive route to Ogden; but against the latter's steep grades, sharp curves, and heavy snows at a 7,017-foot elevation, the new railroad had maintained Bogue's one per cent compensated grade with a maximum curvature of 10°, and crossed the Sierra at 5,002-foot elevation. On the basis of "adjusted mileage" in terms of operating costs, it was rated shorter than the other road. Throughout the line there were 4l steel bridges and 44 tunnels. Everything had been designed and built according to the best contemporary standards but there was much need for further ballasting and other finishing touches. Furthermore, the Western Pacific was an integral part of a 13,708-mile nationwide railway system that now reached from San Francisco to Baltimore, with the exception of a short gap between Wheeling, West Virginia, and Connellsville, Pennsylvania. It looked as if George Gould would be successful with his dream of owning coast to coast rails, for work on a missing link, the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal, was being rushed. A DISCOURAGING START Through freight service on the WP was inaugurated on December 1, 1909. Prior to that there had been local freight service, largely between Salt Lake City and Shafter for the Nevada Northern connection to the flourishing mines of Ely. Traffic was disappointingly slim. The daily lading wires to Jeffery were disheartening. During three days in December, for example, 28,140 pounds of merchandise and one car of lumber for Oakland was the total business received at San Francisco, nothing whatever at Oakland, and similar results at other points. Then came a small windfall, a solid fifty-car trainload of wire and nails from the American Steel and Wire Company at Joliet, Illinois, reached Salt Lake City on December 25 and brought Christmas cheer to all connected with the new railway as it rolled west on WP rails. The cheerful mood did not last long. Duringt he latter part of February, 1910, Old Man Winter hit California hard. Except for the Southern Pacific route through Arizona the entire Pacific Slope was isolated from communication with the East by landslides, snow banks and floods. Night and day extra gangs wrestled with slides in the Feather River Canyon and at Altamont Pass; there were four big washouts in the desert between Gerlach and Winnemucca, and serious damage through Palisade Canyon. And to make matters desperate along the whole railroad, the waters of Great Salt Lake began to rise, ate away at the earth fill, and seriously threatened eight miles of line carried on fill and trestles. Consideration was even given to abandoning this track, obtaining trackage rights over the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake route farther south, and building a ten-mile connection west of the Lake. It was not until the latter part of May that operation was returned to normal. AN ENTHUSIASTIC WELCOME Passenger service was not begun until August. On the 22nd of that month, the fine new Oakland station, impressively corniced with eight immense concrete eagles, saw an immense throng gather to greet the first through train, a press special. Promptly on time at 4:15, amid the shrieking of factory whistles from Berkeley to Hayward, engineer Michael Boyle eased her through an Arch of Triumph at Broadway and stopped before the depot. The trip had seen one amazing welcome after another. Crowds had turned out all along the line, towns were decorated, salutes fired, parades and brass bands were everywhere. Children decked out in their Sunday Buster Brown suits or starched eyelet-embroidered dresses had waved flags and tossed flower garlands, while their elders pressed local gifts of grapes or watermelons upon the astounded passengers. In Quincy, 68-year old Arthur Keddie had almost wept as he spoke in welcome from the court house steps. And in Oakland itself, the crowd that surged in Third Street or lined roof-tops and climbed telephone poles for a better view as the train pulled up to the reviewing stand before the station, was as,exuberant as it was immense. A parade of welcome four miles long escorted the passengers and railroad officers to a banquet at the Claremont Country Club. In the flowery language of the day, the San Francisco Call proclaimed: "The great heart of the State throbs at the triumphal entry ... through canyons to the waters of the West, the Western Pacific led its iron stallions down to drink." George Gould was not present to hear the nice words of welcome to his new railroad. But soon thereafter his cushy business car Atalanta (white tie and tails customary at dinner) came West on the rear end of the Overland Express. Gould, with his pretty ex-actress wife and children, was aboard on a tour of inspection. The multi-millionaire railroad magnate made a hit with the "rails" when he took part in an impromptu baseball game at Portola. THE COST ESTIMATES WERE MUCH TOO LOW Gould had not divided the financial responsibility for the Western Pacific among his other railroads, but had placed it all squarely upon the Denver and Rio Grande. By the terms of a mortgage arranged with the Bowling Green Trust Company of New York in 1905, the Rio Grande had underwritten $50 million in WP bonds, and in addition, had agreed to advance any additional funds necessary to complete the line. But building and equipping the Western Pacific had cost almost twice the $39 million estimate and the D&RG had been called on to advance $16 million in cash. The correspondence of Edward T. Jeffery, president of both companies, shows he was greatly worried at these mounting figures and well he might have been for they were to pull both railways into bankruptcy within a few years. WESTERN PACIFIC GOES TO WORK Gould and Jeffery had, however, enabled the Western Pacific to embark on its career with a top-flight staff of officers. C. H. Schlacks, first vice-president, had 30 years of successful railroad experience behind him; he had been general manager of the Colorado Midland and later operating vice-president of the D&RG. Charles M. Levey, second vice-president and general manager had been general superintendent of the Burlington, general manager of its Missouri lines, and third vice-president of the Northern Pacific. T. M. Schumacher, vice-president in charge of traffic of both WP and D&RG, had been general traffic manager of the El Paso and Southwestern, while Edward L. Lomax and Harry M.Adams, passenger and freight traffic managers respectively, were also capable men of wide experience. Such were officers at the helm of the infant railroad. Two of them, Levey and Adams, were destined to become its presidents. But not even supermen could have put the road immediately in the black. The high cost of its construction had already nearly ruined the Rio Grande's credit. This and the terms of the mortgage which forbade any moneys to be spent on branches until the main line had been completed, had prevented the construction of the numerous feeder lines which had originally been contemplated. A worse deficiency was the lack of on-line industries. In San Francisco the road opened with only one industry spur, that of Dunham, Carrigan and Hayden. Most of the plants and warehouses in Northern California were already served by Southern Pacific and Santa Fe. However, they did their best. Almost at once, they succeeded in signing advantageous traffic agreements with the Santa Fe and the Pacific Coast Steamship Company. They pioneered steam road interchange with the new electric interurbans. A secret agreement, made March 26,1906, by Jeffery with Toyo Kisen Kaisha, now became operative and public knowledge. By its terms this Japanese steamship company which had previously interchanged with the Harriman lines would form a through route with the Gould System. The first sailing direct from the Western Pacific Mole took place February 8,1911, when the Nippon Maru pulled away with a load of cotton for the mills of Japan. Eastbound the steamers brought in Oriental fabrics that rolled as million-dollar silk specials on faster than passenger schedules. Fast fruit trains made Chicago from Sacramento over the Gould System in 106 hours, and coast-to-coast package merchandise cars ran over WP, Rio Grande, Missouri Pacific, Wabash and Lackawanna. In the passenger department Lomax was just as active in promoting the beauties and opportunities for sport in the "Grand Canyon of the Feather"; the luxury of the electrically lighted and fanned six-car Atlantic Coast Mail. On - toes solicitation garnered special movements for organizations ranging from the Bartenders Union to the International Purity Congress. A Votes-for-Women Special paused at all stations for observation platform speeches by the Suffragettes in the manner later adopted by presidential candidates. But as the earnest efforts of both traffic branches fell far short of profitable operation the Rio Grande became increasingly concerned at the growing deficits. In 1911 it was forced to suspend dividends on its preferred stock in order to meet the interest coupons on the WP first mortgage bonds. By 1914 it was trying to get the terms of the mortgage altered so as to eliminate this crushing burden. Meeting with no success, its directors decided to default on the coupons due March 1, 1915. As a result Western Pacific was forced into receivership. It was a tragic decision for the Rio Grande and made in the belief that under the contract it was liable only for the interest and not the principal of the WP bonds. The Rio Grande could, at some sacrifice, have met the interest for years, but its directors felt that by precipitating foreclosure and the sale of Western Pacific at auction, their liability would be ended. As it developed the courts held otherwise. The Gould empire was crumbling. In the East the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal project had bankrupted the Wabash in similar fashion to the Rio Grande's downfall. George Gould had been forced out of active control of the great railway system. And, whatever the future of the Western Pacific, it would now be on its own. With the San Francisco Exposition in 1915, slides closing the Panama Canal, growing involvement of the United States in the European War and, particularly, the results of its own development program, WP traffic zoomed. But the property was sold at auction on the steps of the Oakland station on June 28,1916, by a Special Master in Chancery. Three bank clerks, representatives of a bondholders'committee, bid it in. It was quite a contrast to the gala triumph at the same spot a short six years before. REORGANIZATION The Western Pacific Railroad Company had been incorporated by the bondholders a few weeks before, to operate the railway and, subsequent to the auction, the Western Pacific Railroad Corporation was chartered by the same parties as a holding company. Charles M. Levey, who had been second vice-president of the old Company, became president of The Western Pacific Railroad Company. Under his able direction it prospered for many years. One of Levey's first actions was to engage consulting engineer J. W. Kendrick to make an independent survey toward building or acquiring feeder lines. By the terms of its mortgage bonds no branches had been built by the old Company, though Bogue had hopefully kept alive many interesting projects that had been offered. One such was an entrance into Los Angeles through the Malibu Rancho and Santa Monica. Another was a network of interurban lines to cover Oakland, Alameda and Berkeley, which the present WP management can be thankful was never built. As a result of Kendrick's studies a 75 percent interest in theTidewater Southern Railway between Stockton and Turlock was acquired in March, 1917, the Nevada-California-Oregon narrow-gauge line between Reno and the WP main line purchased the following May and standard gauged, and construction of a San Jose branch begun. Several other existing short lines and projects for branches were looked on with favor, but it was not possible to do everything at once. Kendrick made one poor guess when he stated in his report that: "the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern can be of no possible use to the Western Pacific." That line, now a part of WP's subsidiary, the Sacramento Northern, handles steel shipments to and from Columbia Steel at Pittsburg, a very lucrative business. Five heavy articulated mallet locomotives, Nos. 201-205, were ordered from American to work in the Canyon. They were 2-6-6-2's of 80,000 pounds tractive effort. A comprehensive program of building and purchasing freight and passenger cars was also undertaken. This was extremely necessary as under the old regime most of the rolling stock had been leased from the Rio Grande. The old Company had actually owned only two box cars, both of which had been foreign cars forcibly purchased after wrecks. UNCLE SAM TAKES OVER On December 28, 1917, with the United States several months a beligerent in the European War, President Woodrow Wilson seized control of the nation's railroads. The United States Railroad Administration was set up by Congress, headed by William Gibbs McAdoo, Wilson's son-in-law. On July 1, 1918, McAdoo appointed William R. Scott, vice-president of Southern Pacific, to manage that system as well as the Santa Fe Coast Lines and Western Pacific. It was not a happy time for WP, although the USRA added ten Mikado engines, Nos. 301-310, 60,000 pounds tractive effort, to the roster, and although the Feather River Route was carrying heavy trains of war freight and "doughboys." Several of the measures introduced by Scott were bitter pills to the Western Pacific officers. One was the "paired track" operation of S.P. and WP between Winnemucca and Wells, 182 miles, where the tracks were parallel. Another was folding up Western Pacific's ferry and barge service on San Francisco Bay, its passenger trains being diverted to the S.P. Mole and its San Francisco freight moving via Dumbarton cutoff. But on August 31, 1919, Colonel Edward W. Mason, who had come to WP as a car accountant ten years before and served in France with the U. S. Army Railroad Corps, was appointed Federal Manager of the Western Pacific and the road again rejoiced in a family hand on the throttle. On March 1, 1920, when complete independence was achieved again with the return of the roads to private ownership, Mason became general manager, and later vice-president and general manager, a post he was to hold until his retirement on June 30, 1946. Like most railroads the Western Pacific was in deplorable physical condition when the Government relinquished control. After a year's haggling it received almost $9 million in damages. Most of the money went to purchase control, on December 23, 1921, of the Sacramento Northern Railroad, a third-rail electric line between Sacramento and Chico. With restored individuality came much friendlier, if no less competitive, relations with the big neighbor, Southern Pacific. The paired track arrangement originally begun by Scott was discovered to be a good idea and in the mutual interest after all. It was reinstated on March 7, 1924, and an agreement for joint rates and routes was signed by which WP was to bridge at least half of the S.P. traffic between Oregon and Ogden from Winnemucca to Chico on the Sacramento Northern. All Western railroads suffered during the roaring twenties from intensive Panama Canal steamship competition and the WP was no exception. However, its acquisition of subsidiaries and building of branch lines paid off in generally favorable results. Twenty-six more Mikados were bought, Nos. 311-336, and large additions to the rolling stock, including 2,000 refrigerator cars, were made. Upkeep of roadbed, however, left something to be desired. THE LAST OF THE RAILROAD MOGULS COMES TO WP In 1926 Arthur Curtiss James, probably the last of the great railroad financial giants, added control of WP to his large holdings in Great Northern, Northern Pacific, Burlington and other Western railroads. A new era in the history of Western Pacific began at once. James was the son of a man who had been one of "Empire Builder" Jim Hill's principal lieutenants. Railroads were in his blood. There was plenty of money in his pockets, too, for he had just sold the El Paso and Southwestern to the S.P. after that Company had blocked his plans to extend it to the Pacific. Harry M. Adams had left his WP job as freight traffic manager years before. A Union Pacific career had culminated in his recent retirement as vice-president, traffic. James called him back to activity to make him president of Western Pacific. Complete renovation of the property was begun at once. Banks were widened, ties renewed and increased, and new rail laid. Sidings were lengthened in preparation for longer freight trains. The men out on the line were not forgotten either.Included in the improvement plans were 66 residences for section foremen and agents, as well as many well-built, attractive bunk houses for their crews. Face lifting on the existing property was only part of the James program for a greater Western Pacific. His ambitious plans called for the purchase of several shortlines and the building of new branches, practically all of which, however, had been contemplated in the original Gould plans and later recommended by Kendrick's report in 1916. Of these, the following short lines were of the most import: 1) Acquisition of the trolley-powered San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad (for-merly Oakland, Antioch and Eastern) between Oakland and Sacramento. This was accomplished in August, 1927, and merged, January 1, 1929, with the Sacramento Northern. 2) Acquisition of the Petaluma and Santa Rosa Railway, also electric, as a foot in the door toward the Redwood Empire. This was vetoed by the Commissions and the line was purchased by the S.P. Of the proposed new branches, three were of major importance: 1) An extension, utilizing a portion of the Tidewater Southern,southward down the San Joaquin Valley to Fresno. After a bitter battle of words, this was barred by the regulatory Commissions who held that additional rail service in the Valley was not justified. 2) Direct rail entrance into San Francisco by means of a line up the Peninsula. This was opposed most vigorously by the S.P., but nevertheless won the approval of the Commissions. Complete rights of way were secured, but although time extensions were several times granted by the I.C.C., this project was a victim of the approaching Great Depression. 3) The third major extension, and the one which was actually built and put into operation despite desperate opposition, was the link between Western Pacific and the Great Northern now known as the Inside Gateway. WP built 112 miles north out of Keddie connecting with the Great Northern's 88-mile extension at Bieber, California. This was a most important project, making Western Pacific a north and south carrier through its connection with the Santa Fe at Stockton, in addition to being an east and west transcontinental. The Western Pacific's part of the construction was through very rugged country. However, construction methods had improved vastly. The nine tunnels on the route were all built within a year and by the same crew - quite different from the endless pecking at Spring Garden and Chilcoot 25 years before. A tunnel had been planned at Milepost 5, near Indian Falls, but by blasting off the mountainside with a single charge, a deep cut was substituted. Fifty tons of black powder and two tons of dynamite lifted a sidehill as tall as a ten-story building, as long as two city blocks, and as wide as one. THE LAST GOLD SPIKE At Bieber, on November 10, 1931, amid the icy blasts of a snow-bearing gale from the North and the equally frigid financial storms of the deepening depression, Arthur Curtiss James drove a spike of Oroville gold before several train-loads of dignitaries. After the ceremonies the guests tore down the grandstand and with it built a bonfire to keep from freezing. No such easy refuge offered for the Nation's railroads. Traffic continued to shrink as factories closed their doors. One after another, they were going into bankruptcy. The Western Pacific Railroad Company defaulted on its bond interest due March 1, 1935. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which had already made loans to the Company in an effort to avert this outcome, now requested the officers to prepare a plan of reorganization. SECOND REORGANIZATION Accordingly, the WP filed a petition and plan for voluntary reorganization under Section 77, providing for a two-thirds reduction in annual charges and a 50 per cent slash in capitalization. Other plans were submitted by the James' interest (Arthur Curtiss James had died in 1941) and it was not until 1944 that the courts finally approved a stringent plan which cut the fixed debt to a quarter of what it had been, and found the capital stock to be without equity. This, of course, had been held by the Western Pacific Railroad Corporation which the bondholders of 1916 had organized. The $18 million program of placing the railroad in first-class shape which James had turned over to President Adams in the late twenties had been only half completed. By now the depression starved railroad was down at the heels again. A three-year rehabilitation program was initiated in 1936 with R.F.C. funds, while the road was still undertrusteeship. It was actually a delayed continuation of the James plan. Eighty-five pound rail through the Feather River Canyon was replaced with 112-pound steel. Ten mountain-type passenger engines (Nos. 171-180) wer bought from the Florida East Coast Railway in 1936 and eliminated helper engines on varnish trains. Eleven more mallets were added in 1938. Passenge cars were modernized with air-conditioning and new freight cars were added. Faster through schedules to the East had become possible with the Rio Grande's completion of the Dotsero cutoff and use of the Moffat Tunnel in 1934. WAR AGAIN And so it was that Pearl Harbor and what followed found Western Pacific in excellent shape. More than 700 miles of main line track had been laid with 100 and 112-pound rail. Among the 150 WP locomotives were 17 heavy Mallets, capable of handling most freight trains without helpers. In addition 10 engines were leased from the Rio Grande and three from the Duluth Missabe & Iron Range. Furthermore, three 5,400 hp. diesel-electric road freight locomotives were ordered in 1942 and received the following year. These three engines were operated as a"flying squadron" anywhere on the line as traffic conditions required. Only one other railroad, the Santa Fe, had preceded WP in the use of diesel-electric road engines for freight service. It was fortunate that the railroad was so well prepared, for traffic soared far beyond the most optimistic day dreams of the past. Freight more than doubled during the first year of the war while passenger business went up 600 percent. Both kept climbing. It was not unknown for the Exposition Flyer, the road's only through passenger train, to go out in as many as eight sections. Daily engine utilization had to be materially increased, and was. Yard facilities were enlarged. And in the Canyon, which otherwise would almost certainly have developed into an operating bottleneck with the great number of trains that were rolling, centralized traffic control was installed at a cost of almost $1 1/2 million. The first stretch, between Portola and Belden, went into operation in late 1944 and was extended to Oroville by June, 1945. With this heavy traffic came prosperity to the reorganized company. The funded debt was reduced from $38 million to $20 million, while regular dividends were paid. Charles Elsey had become president in 1932. He had joined Western Pacific as assistant treasurer in 1907, while the first rails were being laid, and had seen the recurrent fat and lean years that followed. As president, he had guided it through the Depression and through the War which followed. Under his leadership three projects had been started that would prove the firm foundation of the railroad's future-dieselization, centralized traffic control, and the California Zephyr. At 68, he decided it was time to retire. Retirement was also breathing down the neck of his logical successor, Harry A.Mitchell, who had succeeded Colonel E.W. Mason as vice-president and general manager in July, 1946. Mitchell had come to WP as president of the Sacramento Northern. And now he became chief executive of the parent road for the first six months of 1949. A feature of his administration wasthe debut of the California Zephyr, an event that the men and women of Western Pacific had awaited impatiently for more than a decade. THE CALIFORNIA ZEPHYR For it was during the latter part of 1937 that Western Pacific, Rio Grande and Burlington first laid plans for a daily, diesel-powered streamliner between San Francisco and Chicago. A downward business trend the following year put the plans on the shelf. The War put them on ice. In the long run it was just as well. For on November 16, 1947, the General Motors experimental Train of Tomorrow arrived at Salt Lake City and when the Western Pacific officers had boarded it at Portola and found their way into its domes, they realized at once that only a vista-dome train would do. Orders for the California Zephyr equipment had been placed with The Budd Company in the fall of 1945, but because of the backlog of orders, work on the cars had not been started, and the specifications were altered to provide five vista-domes on each of the six trains necessary for daily service. The California Zephyr went into service on March 20,1949. Never has a new train met with more immediate and complete popular acceptance and become a national by-word. NEW MANAGEMENT AND NEW ACHIEVEMENTS For the best man to succeed Mitchell as President, the Western Pacific Directors had combed the country. They found him in Frederic B. Whitman, who had already established a nationwide reputation for advanced railroad management practices and was then general superintendent of the Burlington, as President Levey had once been. Whitman came to the property in late 1948 as executive vice-president and became chief executive on July 1, 1949. As his right-hand man, he brought Harry C. Munson, assistant general manager of the Milwaukee Road to be vice-president and general manager. During the four years in which Whitman has been president, he has firmly established the Western Pacific not only as a first-class transcontinental line, but as a leader in railroad progress as well. The road is now completely dieselized, completely undercentralized traffic control (except for paired track, extensions and branches). Switches are kept free of snow by automatic heaters operated from the same traffic control boards, and slide detector fences flash their warnings there also. Switch engines and yardmasters are joined by radio. So are the WP tugs on the Bay and soon road engines and cabooses will also be radio equipped. Car ownership has been materially increased. With these technological advances have come faster schedules and top-bracket operating records. By various standard criteria of railroad service and efficiency such as "gross ton miles per freight train hour," "car miles per car day," "train miles per freight train hour," etc., Western Pacific is now usually found among the upper few and often at the top. The road has also become recognized as a pioneer of improved equipment. It was first to buy and make available to shippers of fragile merchandise the "Compartmentizer" box cars which have been so successful in reducing damaged lading; first to try out and buy the Budd rail-diesel cars which are now being ordered all around the world; first with many similar projects. And the public, largely, knows this. Partly due to growing pride in their railroad and partly as a result of the candid, impartial and enlightened human relations policies which President Whitman has introduced, the men and women of Western Pacific are finding, more than ever, satisfaction in being part of a great enterprise. Many of the elders remember how in the lean years they had heard their railroad called the "Wobbly." They hadn't liked it. Nevertheless, they had gone ahead with the job and often performed near-miracles of operation with little more than bare hands. Now, they enjoy the change. Half a century has passed since the "Preliminary Meeting" on March 3,1903. These fifty years have seen the world change more than fifty centuries before them. These fifty years have also proved that the Western Pacific project was, despite its ups and downs, a sound business concept and a necessary development in the public interest. That the revolutionary changes in American life did not lessen but rather increased the need for their railroad is a tribute to the pioneers of Western Pacific. The owners of a pretty ankle no longer need fear jail if she shows it. But the college professors are still talking about the evils of football. Trains and railroads differ greatly from those of fifty years ago. But essentially they are much the same. Fifty years from now, someone writing the history of Western Pacific will very likely make a similar observation about the first century. All aboard for the second fifty years! In 1982, the Union Pacific, Missouri Pacific and Western Pacific railroads merged.

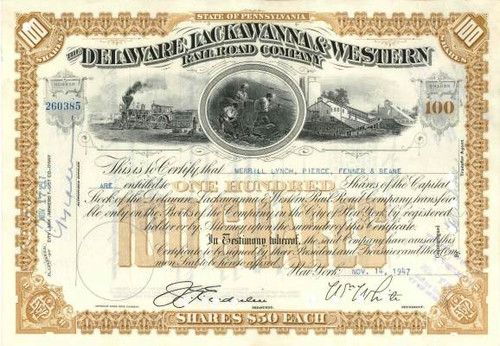

Certificate Vignette

Company logo