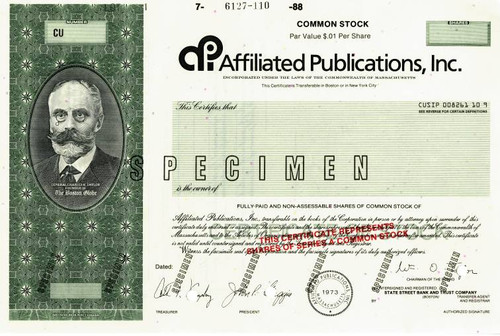

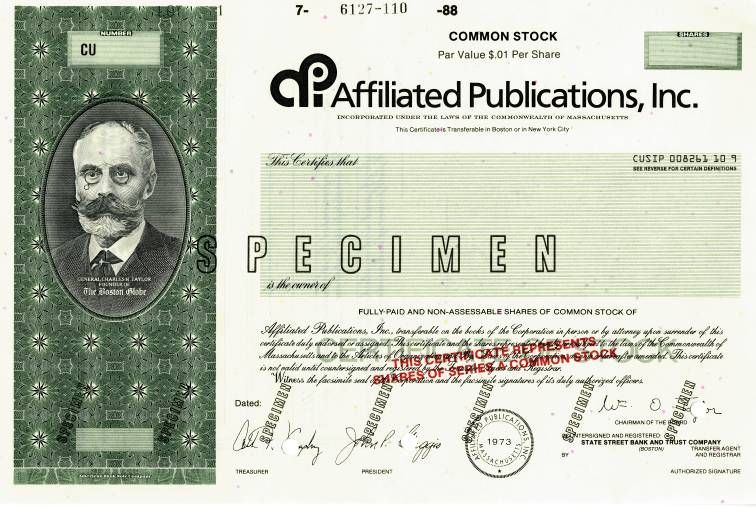

Beautiful specimen certificate from the Affiliated Publications, Inc. printed in 1988. This historic document was printed by the American Bank Note Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of the company's founder, Charles H. Taylor. This item has the printed signatures of the Company's Chairman, William O. Taylor, President, John P. Giuggio and CFO, Arthur F. Kingsbury and is over 34 years old.

Certificate

The Boston Globe was a private company until 1973 when it went public under the name Affiliated Publications. It continued to be managed by the descendants of Charles H. Taylor. In 1993, The New York Times Company purchased Affiliated Publications for US$1.1 billion, making The Boston Globe a wholly owned subsidiary of The New York Times' parent. The Jordan and Taylor families received substantial New York Times Company stock, but the last Taylor family members have since left management. In 1988, Affiliated Publications owned about 43 percent of McCaw Cellular which was the largest cellular telephone operator, at the time, in the United States and Bob Kerstein was a Senior Vice President and Cellular CFO. Boston.com, the online edition of The Boston Globe, was launched on the World Wide Web in 1995.Consistently ranked among the top ten newspaper websites in America, it has won numerous national awards and took two regional Emmy Awards in 2009. In February 2013, The New York Times Company announced that it would sell the New England Media Group, which encompasses the Globe ; bids were received by six parties, of them included John Gormally (then-owner of WGGB-TV in Springfield, Massachusetts), another group included members of former Globe publishers, the Taylor family, and Boston Red Sox principal owner John W. Henry, who bid for the paper through the New England Sports Network (majority owned by Fenway Sports Group alongside the Boston Bruins). However, after the NESN group dropped out of the running to buy the paper, Henry made his own separate bid to purchase The Globe in July 2013.[ On October 24, 2013, he took ownership of The Globe, at a $70 million purchase price. On January 30, 2014, Henry named himself publisher and named Mike Sheehan, a prominent former Boston ad executive, to be CEO. As of January 2017, Doug Franklin replaced Mike Sheehan as CEO,then Franklin resigned after six months in the position, in July 2017, as a result of strategic conflicts with owner Henry. Company History: Affiliated Publications, Inc., is the owner and operator of The Boston Globe, the principal newspaper of the Boston metropolitan area and the surrounding states of New England. Run by one family for over a century, this journal has served as a civic institution, rising slowly to prominence over its many competitors, almost all of which are now defunct. In the 1970s, the owners of the Globe sold stock to the public for the first time and expanded into a number of new fields, seeking to build the Globe into a full-fledged media and communications conglomerate. After 20 years of this activity, however, the company came more or less full circle, concentrating again most fully on the Globe as the center of its activities. The Boston Globe was founded in 1872 by a group of six prominent Boston businessmen who put up a total of &Dollar;100,000 to start a new journal in a city that already had ten of them. The new paper's first issue came out on March 4, 1872. Published only on weekday mornings, it sold for four cents and featured news of local cultural events, as well as a summary of recent sermons from Boston churches entitled "The Sunday Pulpit." In the paper's early months, advertising revenue was scarce and the enterprise's initial capitalization was quickly depleted. In November 1872 Boston was struck by a devastating fire, which wiped out much of the city. Although The Globe's building was spared, its financial situation was not improved, and by June of the following year, the failing paper's backers had begun to pull out. In an effort to resurrect the Globe, its remaining owners convinced veteran newpaperman Charles H. Taylor to join the paper. Taylor was a printer, reporter, and Civil War veteran whose own monthly journal, the American Homes Magazine, had suffered a major setback in the fire. Taylor had previously worked as a correspondent for the New York Tribune, covering news all across New England, and in politics, as the secretary to the governor of Massachusetts, as a state representative, and as the clerk of the state House of Representatives. In August 1873 Taylor began his association with the Globe. By December of that year, he had signed a two-year contract as general manager. At the same time, the Globe appointed a new editor, Edwin Munroe Bacon, who, though only 29 years old, had worked as a correspondent for a New York paper for ten years. Under the leadership of these two men, the Globe began its climb to preeminence in the Boston newspaper world. The early stages of this process were not easy, as the Globe combatted the effects of a financial crash and panic in 173 that lasted throughout the rest of the decade. The paper reduced its price per copy to three cents, increased advertising incrementally, and tried to raise its circulation. Issues were produced on a single printing press and featured woodcuts and cartoons as illustrations. In 1877 the Globe printed its first story transmitted by Alexander Graham Bell's new invention, the telephone, after a reporter relayed an account of a promotional speech by Bell to an assistant in Boston over the wires set up for Bell's demonstration. Despite these technological advances, the paper continued to lose money. In 1878 the Globe was reorganized when Eben Jordan, owner of the Jordan Marsh department store and one of the paper's original founders, paid off the Globe's debts and put it on a sound financial footing. Eventually, taylor and Jordan would split ownership of the paper evenly, although Taylor alone managed the business. The newpaper's newfound financial security enabled Taylor to introduce a Sunday edition and an evening paper. In addition, he changed the Glob's content, switching its political loyalties from the Republican to Democratic party, introducing a higher standard of impartiality and objectivity in reporting, and adding sections to appeal to women and children. These innovations, combined with a drop in price to two cents, resulted in a dramatic increase in circulation for the Globe. Between 1878 and 1881 the number of copies sold increased from 8,000 to 30,000. In 1879 the paper broke even for the first time, and by the end of the 1880s, the Globe had become the dominant paper of the New England region. Taking note of the demographics of Boston, the paper cultivated the city's burgeoning population of Irish immigrants and supported the crusades of organized labor. Not unrelated to this, the paper instituted "Help Wanted" and "Situations Wanted" advertisements, which would grow into a major source of revenue. In 1884 another key member of the Globe's staff was hired when James Morgan, a 22-year-old Kentucky telegraph operator who had previously worked as the Boston correspondent for the fledgling United Press syndicate, was hired as an editor. Morgan soon became a reporter and covered the political beat for more than 60 years. Throughout his long tenure on the Globe, Morgan enjoyed the complete confidence of Taylor and his descendents, and his sensibility shaped the Globe throughout that time. In the mid-1880s the Globe added the columns devoted to the concerns of women to its Sunday edition, in line with the suffragist sentiment of the day. This helped to push the paper's circulation above 100,000 in 1886. The following year, the paper moved into a new building, with space for new presses, to produce a much larger number of newspapers. At seven stories, the Globe building was the tallest on the Boston street that would come to be known as "Newspaper Row." Within five years the Globe claimed a circulation of 200,000. The purchase of a second building enabled the Globe to add an array of new equipment and services, including ten telegraph operators and a linotype machine, which could be used to set type more quickly and efficiently. Reporters began to use typewriters to turn out their copy, and papers were delivered by horse-drawn wagon and by train to outlying areas. In 1894 the paper introduced color printing. Three years later, this innovation enabled the Globe to introduce color comics to its product. With this and other new features attracting readers, the level of advertising in the Globe continued to grow throughout the 1890s, despite the general economic recession. Continuity in running the Globe was assured in the 1890s when all tree of Taylor's sons joined the family business. By the end of the century, the paper's days of innovation were over. The Globe had taken on a staid, institutional quality, as it established itself as the foremost journal of the New England region. With the exception of the period covering the Spanish-American War, when the sales of all newspapers went up dramatically, the Globe's circulation stabilized, rising incrementally as it kept pace with the size of the community it covered. In the early years of the twentieth century, two brash upstart papers arose to challenge the Globe in Boston, and the sensationalism of these new competitors paradoxically contributed to the Globe's emphasis on conventional news coverage. The paper relied on its large staff and heavy use of lighter features to cover the news thoroughly and keep readers interested in reading it during the quiet years before the First World War. When World War I broke out on August 14, 1914, the Globe quickly published dispatches from war correspondents in Europe. The paper also became embroiled in the controversy over whether or not the United Stated should maintain its isolationist stance or become more involved in the war. By 1916, the paper, which had moved from its early Democratic boosterism to a solid middle-of-the-road position, had allied itself firmly with the progressive policies of Woodrow Wilson. When the U.S. did enter the European conflict, the Globe sent its top war reporter to travel with the Yankee Division, made up of men from New England. With the death in June 1921 of Charles Taylor, regarded as the Globe's founder, an era at the paper came to and end. Taylor turned leadership over to his second son, William O. Taylor, who ran the paper in conjunction with his older brother, Charles H. Taylor, Jr. Under their stewardship, the Globe prospered during the general economic boom of the 1920s. The stock market crash of 1029, however, coupled with the ensuing Depression , dramatically changed the country's financial landscape. The economic downturn proved a trying time for the Globe. With the failure of many businesses, advertising revenue dropped off sharply. With no less than five morning papers and four evening papers competing for a shrinking number of dollars, the Globe dropped to third place in circulation in its market. The new leader was the Boston Herald, which had purchased new printing equipment that allowed it to put out a larger, better organized paper. By 1935 the Herald's daily circulation topped the Globe's by 30,000 copies. In the following year, the Globe's profit had dwindled to a mere &Dollar;50,000, and salaries at the paper were cut. In 1937 Charles H. Taylor, Jr., son of the paper's founder, retired. The Globe resorted to contests, previously considered beneath the paper's dignity, to shore up its circulation and enable it to retain its national advertising accounts. The basic problem, however, was not solely financial. The Globe had become a cautious paper with a dulled instinct for the news. Critics charged that the newspaper's coverage of controversial issues was severely lacking and reflected an abdication of civic responsibility. In a sign of the paper's archaic nature, the Globe continued the old-fashioned practice of running advertisements instead of headlines across the tops of its inside pages up until 1936. (Advertisements stayed on the paper's front page well into the 1960s.) By the mid-1930s, however, it was time for a renewal of the Globe's energy. This was accomplished through the retirement in 1937 of many of the Globe's old hands, ad the promotion of younger men into their jobs. Chief among them was Laurence Winship, who became the paper's managing editor. Under Winship the Globe began its slow climb back to preeminence in the Boston market. The newspaper appointed its first picture editor in recognition of the growing importance of photography for a newspaper. The Globe also began to commission and use market research to shape its offerings to readers. It undertook various promotional activities to increase advertising and readership, as well as to bring in young readers. In addition, the Globe began to shift its distribution emphasis from sales at commuter rail stations and other key points to home delivery in the rapidly growing suburbs and the city. These efforts had begun to pay off when the United States entered World War II in late 1941. For the Globe, as for other papers, covering the events in Europe proved a major challenge. The paper strived to present the most accurate account of distant events possible, marking questionable information "unconfirmed" in bold letter over the story. The conflict brought a severe shortage of newsprint. With this came a restriction on the number of advertisements possible and the number of copies available to be sold. Although the Globe's fair handling of these restrictions limited its revenues severely during the war, the paper rebounded during the post-war boom. During the 1950s, the Globe's tradition of sensitivity to the Irish Catholic members of its reading population led it to shrink from any criticism of the demagogic tactics of Senator Joseph McCarthy, just as twenty years earlier it had failed to object to the book bannings and other actions of Boston's corrupt Irish mayor, James Curley. The paper's quiescence began to diminish in the mid-1950s, after the death of publisher William O. Taylor and the ascension of his son., William Davis Taylor, in 1955. The following year, the rival Boston Post went out of business, and the Globe, accustomed to the middle spot in a three-way contest (wich tended to solidify its middle-of-the-road tendencies), found itself in a one-on-one battle with the Boston Herald. Armed with a modern printing plant that produced a clean, sophisticated-looking paper, the Herald's circulation had been increasing for decades while the Globe's remained static, hampered by its outmoded equipment and less attractive product. Both papers sought to increase their advertising and readership in a media market that now included television. Seeking to set itself apart from its competitor, the Globe began to lobby in its pages for civic change and reform. By the end of the 1950s these efforts paid off as the paper picked up a modest number of new readers. In 1958 the Globe abandoned its historic but cramped home on newpaper row and moved south to a modern new plant in the neighborhood of Dorchester, near highways and rail lines. The facility cost &Dollar;14 million and was partly funded by a loan from the John Hancock Life Insurance Company. It was the first time that the paper had sought outside financing since its early years. The new plant allowed the Globe to produce larger editions than its competitor, and the daily morning paper's circulation increased by 100,000 in the next seven years as the Globe took a commanding lead in its war with the Herald. In the 1960s the Globe fully came into its own as an activist journal, taking strong editorial positions on controversial issues and lobbying for civic improvements under the editorial leadership of Laurence Winship's son Thomas, who succeeded his father as editor of the paper in 1965. These efforts were rewarded in 1965 when the paper won the first Pulitzer Prize to be awarded to a Boston journal in 45 years. Under the stewardship of the younger Winship, the Globe moved firmly from a staff of reporters with general assignments to the development of a pool of specialized writers who brought a higher level of expertise and background to the topics they covered. The Globe added critics of the arts, and also sought to recruit younger and more ethnically diverse reporters. Throughout the 1960s, the Boston Globe continued to expand the printing capacity at its Dorchester plant, and in 1968 the paper introduced multiple sections to its large Sunday edition paper. The following year, the paper redid its typeface and design in search of a more modern look. With these changes, the paper continued to show steady gains in Sunday and morning readership, while circulation for the evening edition fell as the Boston area's population shifted to the suburbs. In the 1970s the Globe continued its trend toward activist reporting as it covered such stories as the U.S. involvement in Vietnam and the burgeoning counterculture. In August 1973 the Globe's financial structure underwent a major change when the trustees of Eben Jordan's trust and various members of the Taylor family sold stock in the company to the public for the first time. The stock sale was structured so that the Jordan trust and Taylor family effectively remained in control of the new company, named Affiliated Publications, Inc. With the capital raised by the sale, Affiliated began to expand its scope of operations beyond its core urban newspaper tradition into new forms of media and communications. In late 1975 the company acquired Research Analysis Corporation to conduct and market demographic surveys. The following year the company purchased radio stations in New York and Ohio, and bought a small Massachusetts newspaper. Affiliated's media purchases continued in the late 1970s, as the company added six radio stations around the country to its holdings. In 1981 the company entered a new field when it purchased a 45-percent share in McCaw Cellular Communications, a Washington-state-based cable television operator, for &Dollar;12 million. The following year, Affiliated and McCaw augmented their holdings by buying two West Coast cable television properties, the Southern Oregon Broadcasting Company and Pacific Teletronics, Inc. In 1983 Affiliated made a major investment in what remained the centerpiece of its holdings, the Boston Globe, when it opened a satellite printing press for the newspaper in Billerica, Massachusetts, outside Boston. Newspaper pages were made up at the main Globe facility in town and then sent over wires to the plant to be printed. Two years later, this move allowed the Globe to produce its largest daily issue ever--216 pages--and the largest Sunday paper, totaling 1,050 pages, one month later on December 1, 1985. Following these successes, Affiliated began to streamline its operations. First, the company sold off its radio properties, divesting itself of its first two purchases separately, and then handing off an additional nine radio stations to EZ Communications for &Dollar;65.5 million in 1986. At the end of that year, Affiliated and McCaw sold their cable television operations for &Dollar;755 million. Affiliated then announced plans to enter the fledgling cellular phone industry through McCaw, with expectations that profits in the largely untried field would be high. In a move more in line with its traditional strength in print media, Affiliated purchased Billboard Publications, Inc. (BPI), a trade magazine publisher, for &Dollar;100 million in 1987. The following year, this subsidiary, now called BPI Communications, Inc., bought two publications--Plants, Sites & Parks and The Hollywood Reporter. Affiliated also increased its holdings in McCaw slightly. The acquisitions expanded the company's profits to more than &Dollar;200 million for the fiscal year ending in December 1987. By the end of 1988, however, the economy of New England fell into a recession, sharply limiting the profitability of the Globe. In an effort to bring order to its somewhat disparate activities, Affiliated reorganized itself in early 1989, spinning off its core publishing businesses, the Globe Newspaper Company and BPI Communications, Inc., and merging its remaining businesses into McCaw. These transactions, all accomplished on a tax-free basis, left Affiliated's stockholders holding both Affiliated stock and McCaw stock. In total, Affiliated had invested &Dollar;80 million into McCaw. On May 31, 1989, the day these transactions were finalized, the public market valuation of Affiliated's stock interest in McCaw was approximately &Dollar;2.6 billion. As part of the process of returning to its roots, Affiliated purchased a majority interest in Adweek magazine in 1990 through BPI Communications, continuing the company's focus on print media. Affiliated turned a profit in 1989 and 1990. In the throes of regional recession, however, Affiliated's operating income in 1991 was only one third of what it had been in 1988. Affiliated decided to streamline its operations further, selling off two-thirds of its BPI Communications, Inc., subsidiary to a partnership formed by the subsidiary's management and a venture capital house. In an effort to adapt to the changing advertising climate for the Globe, the company created Community Direct, Inc., to provide specialized marketing services to Globe advertisers. As Affiliated moved into the mid-1990s, it looked to the Boston Globe, its first and principal holding, as the focus of its activities. Keeping this institution, founded in the nineteenth century, relevant and profitable in the twenty-first century will comprise the company's main challenge in the years to come. Source: International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 7. St. James Press, 1993. and Wikipedia.

About Specimen Certificates Specimen Certificates are actual certificates that have never been issued. They were usually kept by the printers in their permanent archives as their only example of a particular certificate. Sometimes you will see a hand stamp on the certificate that says "Do not remove from file". Specimens were also used to show prospective clients different types of certificate designs that were available. Specimen certificates are usually much scarcer than issued certificates. In fact, many times they are the only way to get a certificate for a particular company because the issued certificates were redeemed and destroyed. In a few instances, Specimen certificates were made for a company but were never used because a different design was chosen by the company. These certificates are normally stamped "Specimen" or they have small holes spelling the word specimen. Most of the time they don't have a serial number, or they have a serial number of 00000. This is an exciting sector of the hobby that has grown in popularity over the past several years.