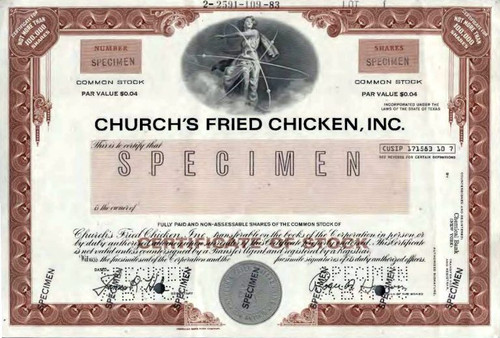

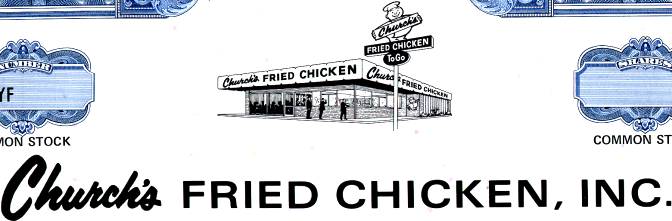

Beautifully engraved Specimen certificate from the Church's Fried Chicken, Inc. in 1969. This historic document was printed by the American Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of Church's Fried Chicken restaurant. This item has the printed signatures of the Company's President, George W. (Bill) Church, Jr and Secretary.

Certificate Vignette A division of AFC Enterprises, Inc., Church's Chicken owns and franchises more than 1,500 fast food chicken restaurants in some 30 states and a dozen countries. About 80 percent of the units are franchised operations. Church's menu centers around Southern-style chicken and features such side dishes as mashed potatoes and gravy, fried okra, cole slaw, Honey Butter Biscuits and Jalapeno Cheese Bombers. In addition to Church's, the parent company owns the Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits chain. Since mid-2004, AFC has been looking to sell off Church's to concentrate on Popeyes. Church's founder was George W. Church, Sr. After retiring from a career in the poultry business, working as an incubator salesman, Church was 65 when he decided to launch a business selling fried chicken, pursuing a fast food concept that was ahead of its time. He kept overhead to a minimum and concentrated on offering a high-quality product at a low cost, prepared for carryout to appeal to the increasingly mobile lifestyle of a post-World War II population. In 1952, he opened a walk-up restaurant that was little more than a stand across the street from the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. It was called "Church's Fried Chicken to Go," an apt name since the restaurant only offered takeout service and sold nothing but fried chicken. As a novelty, the cookers were located next to the window, allowing customers to watch their orders being prepared. It was not until 1955 that he added French fries and jalapenos to the menu. The restaurant was a success, prompting Church to open three more restaurants in San Antonio. However, George Church would not live to see his concept grow further. He died in 1956, and other members of his family took over the operation. It was George W. (Bill) Church, Jr., who fostered the dream of one day spreading Church's Fried Chicken across the country. When he took over the management of the company in 1962, there were eight locations in San Antonio, and for the time being he was content to concentrate on that limited market. Three years later, Church and his older brother Richard made a key contribution when they developed a marinating formula that could be made virtually anywhere. As a result, Church would be able to spread beyond San Antonio and still maintain a level of quality control on their signature fried chicken. In was also in 1965 that J. David Bamberger joined forces with Church to launch a separate franchise operation. Bamberger grew up poor in Ohio during the Depression on a four-acre farm that lacked running water and electricity. He worked his way through college by selling Kirby vacuum cleaners on his 40-mile commute to school each day, and after graduating with a business administration degree he stayed on with Kirby. In 1951, he was assigned to work in Tyler, Texas, and later transferred to San Antonio. Bamberger was an exceptional salesman and an even more dynamic motivator of a sales force he managed. One of his salesmen was Bill Church. As an investor and executive, Bamberger played a key role in the expansion of Church's Fried Chicken, which became the first Texas-based fast-food chain to go national. His idea was to locate units in poor urban neighborhoods, areas that other chains like Kentucky Fried Chicken avoided. About breaking new ground in the hiring and education of employees, Bamberger told Texas Monthly in a 2000 profile, "I sold it to Bill that this was just a step above door-to-door vacuum cleaner sales. We're gonna take the people who are the first to be laid off in a construction job and take them inside, teach them how to clean their fingernails--no one wants to see their chicken handed to them by someone who had to change his car battery that morning--tie a necktie, how to use deodorant, and say, 'Thank you.'" In 1967, the first units opened in five other Texas cities, so that by the following year the company was generating sales of $2.7 million from 17 restaurants. The Church family sold its interest in 1968 to the franchise company started by Bamberger and Bill Church. A year later, to fuel the expansion of the chain, the business was incorporated in 1969 as Church's Fried Chicken and taken public. By the end of the year, Church's operated more than 100 restaurants located in seven states. Church's tried to catch up with the segment leader, Kentucky Fried Chicken. By the end of 1974, the chain had grown to 487 units located in 22 states, with total revenues in excess of $100 million. However, CEO Bill Church and Bamberger, his executive vice-president, were no longer in agreement on how to continue growing the business. In 1974, Bamberger quit, citing "philosophical differences," although he remained the company's largest shareholder, owning 1.2 million shares. Picking up the slack was Roger A. Harvin, a childhood friend of Bill Church, who was trained as a plant pathologist but went into the restaurant business in 1967 when he became assistant manager of three Texas Church's restaurants. He then worked his way up through the ranks, became president in 1975, and took on increasing responsibility as Bill Church became less involved in the business. In 1980, Church resigned as chairman of the corporation and Harvin replaced him. Church's enjoyed a strong run in the 1970s, emerging as the second-largest chain in the chicken segment. The company began to expand internationally in 1979, opening a restaurant in Japan. Also during that decade, Church's became involved in the burger segment, launching a chain called G.W. Jrs. By 1982, the company would operate 62 of these restaurants in Texas. During the early 1980s, however, Church's growth stagnated. There was also disunity at the top levels of management. Early in 1983, James Parker, executive vice-president of operations quit. He was soon followed by chief financial officer William Storm, who resigned according to a company official because of "philosophical differences with management." After leaving the company, Storm criticized Harvin's reluctance to spend money on new concepts or experimentation. Harvin attempted to be more aggressive in the months following Storm's departure. He made a greater commitment to advertising and acquired the Houston-based Ron's Krispy Fried Chicken, a more upscale 74-unit chain that the company hoped would establish it in more upscale, suburban markets, as opposed to Church's traditional inner-city base. In addition, Church's launched a new concept, Charro's, to compete in the charbroiled, Mexican-style area. However, by early November 1983, Harvin resigned and Bamberger returned to replace him. According to press reports, Bamberger engineered Harvin's ouster and stepped in to protect his investment in Church's. Bamberger served as Church's president on an interim basis until he was able to lure Richard F. Sherman away from the Hardees restaurant chain. The company soon closed more than 100 units and pumped up the advertising budget. Efforts were also made to grow the G.W. Jrs. chain, but management soon gave up on the concept, exiting the burger market in 1985. Because of Bamberger's return, Church's became the subject of constant takeover rumors which maintained that Bamberger was simply dressing up the company in order to sell it. Also during this period, Church's was part of a bizarre rumor that became something of an urban legend in the African-American communities of Memphis, Denver, Detroit, Chicago, and San Diego. According to the stories, Church's was owned by the Klu Klux Klan, which incorporated something into the chicken recipe that would render African-American males either impotent or sterile. The rumors, however bereft of logic, did have a negative impact on Church's sales, according to company memos that came to light during a court case involving a franchisee that sued the company because it had not informed him about the rumors. In 1985, Church's generated $548 million from 1,500 units, of which fewer than 300 were franchise operations. Sherman and Bamberger tried to strike a 50-50 balance between company-owned and franchised operations as well as taking steps, such as introducing catfish to the menu, to revitalize the chain. Despite management's adoption of a long-range strategy, Church's was still dogged by takeover speculation, for which there was a sound underpinning: most of the company-owned restaurants were located on land owned by Church's, which made the company more valuable than might appear on the surface. In 1987, Sherman resigned and joined forces with Stephen Lynn, the CEO of Sonic Industries and a former Kentucky Fried Chicken executive, to make a bid for Church's. While this $12.25-a-share buyout offer was rejected, another would succeed in early 1989, engineered by Al Copeland, the flamboyant founder of Popeyes Famous Fried Chicken. Like Bamberger, Copeland grew up poor, a high-school dropout in New Orleans who worked as a soda jerk to help support his mother. After working for his older brother, who ran a chain of donut shops, Copeland became a franchisee when he was just 18. He was running a successful donut operation when he decided to get into the chicken fast food business after a Kentucky Fried Chicken store opened in New Orleans. In 1971, he launched Chicken on the Run, which at first proved to be a disaster. Only when he adopted a spicier Cajun-inspired recipe did the business turn around. He also changed the name to Popeyes Mighty Good Fried Chicken, an allusion to Popeye Doyle, the detective played by Gene Hackman in a hit film at the time, The French Connection. Copeland began franchising in 1977, and by the early 1980s Popeyes trailed only Kentucky Fried Chicken and Church's as the largest fast-food chicken chains. Copeland was a one-man management team, but his interests expanded beyond Popeyes to include other restaurant concepts, so that by 1988 he established the positions of president, chief financial officer, and executive vice-president of operations. Two of these slots were filled by executives he hired away from Church's, including CFO Lewis Kilbourne. Copeland was interested in expanding through acquisitions and soon targeted Church's, which led to speculation that Kilbourne, who had signed an agreement not to disclose confidential information when he left Church's, might have revealed company secrets to help Copeland craft an offer. At the very least, Kilbourne was able to persuade Copeland to make a bid despite the two chains' seeming incompatibility. Popeyes, although smaller, was decidedly more upscale than Church's. According to Restaurant Business, "Kilbourne's thinking went this way. Church's was a valid concept that had overexpanded. It was an ideal acquisition target; it had no debt and it was rich in real estate, with some 70 percent of the stores company-owned. Popeyes would buy Church's, slash the losers, and sell off competing stores to Popeyes franchisees for conversion and also to Church's franchises. A much smaller but profitable chain of 600 to 800 stores would be left. Sale proceeds would be used to pare down debt." In October 1988, Copeland offered $8 a share, or $300 million, but by now Church's was headed by Ernie Renaud, the former president of Long John Silver's, and he was showing some success in his turnaround efforts, closing down unprofitable stores and building up the sales volumes in the remaining units. As a result, the price went up, but in February 1989 Copeland finally prevailed, although the final cost was $480 million, funded by junk bonds. The key to making the deal work was the immediate closing of another 100 money-losing units and the sell off of 250 more units. However, after closing the losing stores, Copeland failed to sell off properties because he asked franchisees to pay unrealistic prices. After the first year, only 54 Church's were sold to franchisees instead of 250. Franchisees also became disgruntled because Copeland increased the cost of a reformulated marinade mix as well as the ad fund charges. Efforts to convert Church's stores to the Popeyes' format also proved disappointing. By 1990, Copeland Enterprises was in default on $391 million in debts, and in April 1991 the company filed for bankruptcy protection. In October 1992, the court approved a plan by a group of Copeland's creditors that resulted in the creation of America's Favorite Chicken Company, Inc. (AFC) to serve as the new parent company for Popeyes and Church's. The former president of Arby's Inc., Frank J. Belatti, became AFC chairman and CEO and promptly moved the company's headquarters from New Orleans to Atlanta. He soon launched efforts to improve relationships with franchisees and upgrade operations and quality. In addition, Popeyes and Church's were placed into separate units, and Church's for the first time in years was able to able to grow without being overshadowed by Popeyes. In 1993, Hala Moddelmog was named vice-president of marketing. Three years later, she became president, one of the few women to reach the top ranks in the restaurant industry. She grew up in rural Georgia and worked her way through Georgia Southern College before earning a master's in communications at the University of Georgia. She went to work at Arby's as a marketer in 1981, involved in the chain's development of a popular chicken sandwich. After a stint with Bell South, she took a job with Arby's Franchise Association as vice-president of marketing and strategic planning. She then followed Belatti to Church's, where she set about upgrading the chain's image. A new logo was introduced and the restaurant's decor was improved. As president, she introduced honey-buttered biscuits to replace the plain dinner rolls Church's had been serving and invested in ovens to make sure each unit was able to offer them. Church's pursued a number of ideas during the 1990s to revitalize the business. It opened kiosks and operations in convenience stores and co-branded with the White Castle hamburger chain in several dozen locations. In the mid-1990s, Church's tried a line of Mexican food products, but it proved to be a costly mistake and was quickly discontinued. Nevertheless, the venture taught Moddelmog not to lose sight of what was the core of the Church's franchise. When urged to consider turkey-based additions to the menu, she declined. In 1997, however, she did approve the introduction of spicy chicken wings, which helped to spur a growth in sales. In 1999, Church's added buffalo chicken wings, macaroni and cheese, seasoned beans and rice, and collard greens. Church's ramped up efforts to expand internationally in 2000, with the goal of growing the number of overseas units from 314 in nine countries to 1,000 within four to five years. Central and South American Countries were the immediate target. When Church's celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2002, the chain was 1,500 units in size, a significant increase over the 1,000 restaurants that remained following Copeland's bankruptcy. Although Church's had experienced some setbacks in the previous decade, Moddelmog generally presided over a successful turnaround. By 2004, however, Church's and Popeyes were no longer compatible operations for AFC, as the two chains were beginning to encroach on each another. AFC had already sold most of its Seattle Coffee Co. brand and was looking to sell off its Cinnabon chain. Belatti decided that AFC needed to concentrate on one of its two chicken brands and elected to divest Church's, hiring Bear, Stearns & Co to evaluate the options. Church's was at its peak value, and it also owned more real estate than Popeyes, giving the chain a better chance to arrange financing. To help in the divestiture, AFC decentralized some functions, a change that made Church's more self-sufficient and therefore more attractive to a potential buyer while enabling the chain to be fully prepared as it embarked once again as an independent business. History from StockResearch.pro (Professional Old Stock Certificate Research Service).

About Specimen Certificates Specimen Certificates are actual certificates that have never been issued. They were usually kept by the printers in their permanent archives as their only example of a particular certificate. Sometimes you will see a hand stamp on the certificate that says "Do not remove from file". Specimens were also used to show prospective clients different types of certificate designs that were available. Specimen certificates are usually much scarcer than issued certificates. In fact, many times they are the only way to get a certificate for a particular company because the issued certificates were redeemed and destroyed. In a few instances, Specimen certificates were made for a company but were never used because a different design was chosen by the company. These certificates are normally stamped "Specimen" or they have small holes spelling the word specimen. Most of the time they don't have a serial number, or they have a serial number of 00000. This is an exciting sector of the hobby that has grown in popularity over the past several years.

Certificate Vignette

About Specimen Certificates Specimen Certificates are actual certificates that have never been issued. They were usually kept by the printers in their permanent archives as their only example of a particular certificate. Sometimes you will see a hand stamp on the certificate that says "Do not remove from file". Specimens were also used to show prospective clients different types of certificate designs that were available. Specimen certificates are usually much scarcer than issued certificates. In fact, many times they are the only way to get a certificate for a particular company because the issued certificates were redeemed and destroyed. In a few instances, Specimen certificates were made for a company but were never used because a different design was chosen by the company. These certificates are normally stamped "Specimen" or they have small holes spelling the word specimen. Most of the time they don't have a serial number, or they have a serial number of 00000. This is an exciting sector of the hobby that has grown in popularity over the past several years.