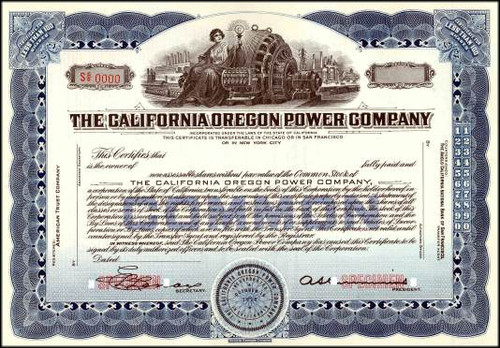

Beautifully engraved Stock certificate from the North American Light and Power Company dated 1944. The certificate has a ornate red border with an vignette of an allegorical woman in the center next to a power generator holding a light bulb. This certificate is hand signed by the company's officers and is over 59 years old.

Certificate Vignette The company was orginally organized to own public utulity properties primarily in the gas and electric area. They has over 108 properties including the Illinois Power and Traction Company, Washington Gas and Electric, Citizens Electric Light Comapany and many more. One of the company's founders was Clement Studebaker, Jr who serverd as Chairman of the Board. December 30, 1941, the SEC implemented a resolution which forced the company to liquidate all of its properties and its existence terminated under the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935. The company began selling its assets in 1942 to comply with this order and became fully liquidared in 1948.

In 1935, the Public Utilities Holding Company Act (PUHCA) was enacted to eliminate unfair practices and other abuses by electricity and natural gas holding companies by requiring federal control and regulation of interstate public utility holding companies. These abuses arose from the inability of individual states to effectively regulate the financial transactions of multistate and multi-layered utility companies that evolved in the 1910s and 1920s. From the very beginning of the U.S. electric power industry in the late 1800s, technology, economics, and regulations have defined the structure of the industry. At the end of the 1800s, transmission was by direct current (DC), involving large copper conductors. DC power could be transmitted economically only over short distances, requiring generation to be built close to its load. Introduction of a reliable alternating current transmission system in 1903, which provided for long distance transmission at less cost than DC, and the introduction of steam turbine generation technology that was more efficient than reciprocating engines, produced a change of corporate structure. At the same time that economies of scale encouraged utility consolidation, utilities were acquiring increasing numbers of subsidiary companies, some with little or no relation to the utilities' primary business. From 1900 through 1920 the number of private electric systems grew from approximately 2,800 to 6,500.(1) Starting in 1920, the number of private electric systems declined dramatically primarily because of consolidation and pyramiding of utilities through holding companies. Not only did many operating utilities, in diverse parts of the country, come under the control of a small number of holding companies, but those holding companies themselves were owned by other holding companies. As many as ten layers separated the top and bottom of some pyramids. By 1932, three groups controlled 45% of the electricity generated in the United States. Although more than two-thirds of the states had public utility commissions of varying powers by 1920, none of these entities had the economic regulatory power of a modern public utility commission. The state public utility commissions were unable to control the multistate nature of holding companies. Prior to enactment of the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA), electric and gas holding companies were characterized as having excessive consumer rates, high debt-to-equity ratios, self-dealing, and increasingly unreliable service. A holding company parent was able to charge its associated utilities exorbitant amounts for services, such as construction of facilities, fuel supply, or billing. Excessive fees charged to operating companies were passed through to consumers as higher rates. Holding companies incurred increasing amounts of debt to finance their interests in a growing number of subsidiaries. The economics of generating and transmitting electricity had changed dramatically since 1900. Economies of scale were not been taken advantage of and the marginal costs (the cost of each additional unit of generation) were less than average cost. The classic monopoly situation existed. Most highly leveraged holding companies that managed to stay solvent during the prosperous 1920s collapsed after the stock market crash because they could not service their debt. Lower demand for electricity resulted in inadequate revenue to meet fixed obligations. As more and more companies went bankrupt, service deteriorated. While there were advantages to the holding company structure, holding company abuses became apparent after the stock market crash in 1929 when investors lost millions of dollars. During the seven-year period between 1929 and 1936, 53 holding companies with combined securities of $1.7 billion went into bankruptcy or receivership. Twenty-three others were forced to default on interest payments or to offer extension plans.(2) In 1928, the Federal Trade Commission issued a report that listed the abusive practices of holding companies.(3) It concluded that the holding company structure was unsound and "frequently a menace to the investor or the consumer or both." As noted earlier, holding companies operated with no federal and little state regulation. The state utility commissions lacked sufficient authority and resources to control holding companies because companies operated generally in many states and had extremely complex structures. The federal government decided regulatory action was required. The Federal Power Act, which established a federal utility regulatory system, was enacted at the same time as the Public Utility Act of 1935(4); these two Acts were intended to work in tandem. Title I of the Public Utility Act of 1935 is known as the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA). PUHCA was enacted to eliminate unfair practices and other abuses by electricity and gas holding companies by requiring federal control and regulation of interstate public utility holding companies. A regulatory bargain was created between utilities and the government. In exchange for an exclusive service territory, utilities are required to provide reliable electric service to all customers at a regulated rate. A holding company under PUHCA is an enterprise that directly or indirectly owns 10% or more of stock in a public utility company. To eliminate the complex and confusing structure of holding companies that had made them almost impossible to regulate, Section 11b of Title I (the "Death Sentence Clause") of PUHCA abolishes all holding companies that were more than twice removed from their operating subsidiaries. All electric and natural gas holding companies are required to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Under PUHCA, the SEC regulates mergers and diversification proposals of holding companies whose subsidiaries engage in retail electricity or natural gas distribution. In addition, PUHCA requires that before purchasing securities or property from another company, a holding company must file for approval with the SEC. Other major sections of PUHCA provide that: registered holding companies and their subsidiaries must have SEC approval prior to issuing securities; operating utilities are forbidden from making loans to their parent holding company; all loans and intercompany financial transactions are regulated by the SEC; the operations of non-exempt holding companies are limited to single and integrated public utility systems and to such businesses that are reasonably incidental or economically necessary or appropriate to the operations of such integrated systems; and, non-exempt holding companies that are subject to SEC regulation must maintain certain accounts and records, which are subject to SEC review. The SEC does allow companies to operate in several areas if this preserves the economy of operation, or if the areas are located in a single state, adjoining states, or contiguous foreign country, and providing that the creation of such a holding company does not inhibit efficient operation or effective regulation.

Certificate Vignette

In 1935, the Public Utilities Holding Company Act (PUHCA) was enacted to eliminate unfair practices and other abuses by electricity and natural gas holding companies by requiring federal control and regulation of interstate public utility holding companies. These abuses arose from the inability of individual states to effectively regulate the financial transactions of multistate and multi-layered utility companies that evolved in the 1910s and 1920s. From the very beginning of the U.S. electric power industry in the late 1800s, technology, economics, and regulations have defined the structure of the industry. At the end of the 1800s, transmission was by direct current (DC), involving large copper conductors. DC power could be transmitted economically only over short distances, requiring generation to be built close to its load. Introduction of a reliable alternating current transmission system in 1903, which provided for long distance transmission at less cost than DC, and the introduction of steam turbine generation technology that was more efficient than reciprocating engines, produced a change of corporate structure. At the same time that economies of scale encouraged utility consolidation, utilities were acquiring increasing numbers of subsidiary companies, some with little or no relation to the utilities' primary business. From 1900 through 1920 the number of private electric systems grew from approximately 2,800 to 6,500.(1) Starting in 1920, the number of private electric systems declined dramatically primarily because of consolidation and pyramiding of utilities through holding companies. Not only did many operating utilities, in diverse parts of the country, come under the control of a small number of holding companies, but those holding companies themselves were owned by other holding companies. As many as ten layers separated the top and bottom of some pyramids. By 1932, three groups controlled 45% of the electricity generated in the United States. Although more than two-thirds of the states had public utility commissions of varying powers by 1920, none of these entities had the economic regulatory power of a modern public utility commission. The state public utility commissions were unable to control the multistate nature of holding companies. Prior to enactment of the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA), electric and gas holding companies were characterized as having excessive consumer rates, high debt-to-equity ratios, self-dealing, and increasingly unreliable service. A holding company parent was able to charge its associated utilities exorbitant amounts for services, such as construction of facilities, fuel supply, or billing. Excessive fees charged to operating companies were passed through to consumers as higher rates. Holding companies incurred increasing amounts of debt to finance their interests in a growing number of subsidiaries. The economics of generating and transmitting electricity had changed dramatically since 1900. Economies of scale were not been taken advantage of and the marginal costs (the cost of each additional unit of generation) were less than average cost. The classic monopoly situation existed. Most highly leveraged holding companies that managed to stay solvent during the prosperous 1920s collapsed after the stock market crash because they could not service their debt. Lower demand for electricity resulted in inadequate revenue to meet fixed obligations. As more and more companies went bankrupt, service deteriorated. While there were advantages to the holding company structure, holding company abuses became apparent after the stock market crash in 1929 when investors lost millions of dollars. During the seven-year period between 1929 and 1936, 53 holding companies with combined securities of $1.7 billion went into bankruptcy or receivership. Twenty-three others were forced to default on interest payments or to offer extension plans.(2) In 1928, the Federal Trade Commission issued a report that listed the abusive practices of holding companies.(3) It concluded that the holding company structure was unsound and "frequently a menace to the investor or the consumer or both." As noted earlier, holding companies operated with no federal and little state regulation. The state utility commissions lacked sufficient authority and resources to control holding companies because companies operated generally in many states and had extremely complex structures. The federal government decided regulatory action was required. The Federal Power Act, which established a federal utility regulatory system, was enacted at the same time as the Public Utility Act of 1935(4); these two Acts were intended to work in tandem. Title I of the Public Utility Act of 1935 is known as the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA). PUHCA was enacted to eliminate unfair practices and other abuses by electricity and gas holding companies by requiring federal control and regulation of interstate public utility holding companies. A regulatory bargain was created between utilities and the government. In exchange for an exclusive service territory, utilities are required to provide reliable electric service to all customers at a regulated rate. A holding company under PUHCA is an enterprise that directly or indirectly owns 10% or more of stock in a public utility company. To eliminate the complex and confusing structure of holding companies that had made them almost impossible to regulate, Section 11b of Title I (the "Death Sentence Clause") of PUHCA abolishes all holding companies that were more than twice removed from their operating subsidiaries. All electric and natural gas holding companies are required to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Under PUHCA, the SEC regulates mergers and diversification proposals of holding companies whose subsidiaries engage in retail electricity or natural gas distribution. In addition, PUHCA requires that before purchasing securities or property from another company, a holding company must file for approval with the SEC. Other major sections of PUHCA provide that: registered holding companies and their subsidiaries must have SEC approval prior to issuing securities; operating utilities are forbidden from making loans to their parent holding company; all loans and intercompany financial transactions are regulated by the SEC; the operations of non-exempt holding companies are limited to single and integrated public utility systems and to such businesses that are reasonably incidental or economically necessary or appropriate to the operations of such integrated systems; and, non-exempt holding companies that are subject to SEC regulation must maintain certain accounts and records, which are subject to SEC review. The SEC does allow companies to operate in several areas if this preserves the economy of operation, or if the areas are located in a single state, adjoining states, or contiguous foreign country, and providing that the creation of such a holding company does not inhibit efficient operation or effective regulation.