Beautifully engraved certificate from the Templar Motors Company issued in 1920. This historic document has an ornate border around it with a vignette of an eagle. This item is hand signed by the Company's President (M. F. Bramley )and Secretary and is over 94 years old.

Certificate Templar Motors was formed by a group of Clevelend investors in 1916, with production starting the following year. Management took the name Templar from a military order founded in Jerusalem by the crusaders about 1118. It chose the Maltese cross as the car's emblem. The corporation's main building, a three-story brick, concrete and steel structure with 300,000 square feet of floor space, still stands at 13000 Athens Ave. It now houses 16 tenants, the largest of which is Lake Erie Screw Products Co. In 1917 a factory consisting of three frame buildings was erected at Halstead and Plover Streets, Lakewood at a cost of $2.5 million. Plant capacity was 5,000 cars a year, though production was never in excess of a third of that. Actually, total output during Templar's short span on the market was only 6,000 units. The first car was completed and displayed in July 1917. A. M. Dean, chief engineer, announced in the trade press that the plant would soon be ready for quantity production. However, with the United States at war, the plant was given over almost entirely to war work, making 155 mm. shells. Nearly 1,000 persons were employed in the munitions operation. Meanwhile, with only token production of automobiles, the organizing of sales and other personnel moved ahead to be ready for full production when the war would end. Save for its engine, the Templar was an assembled car; the engine being of original design and turned out in the company's own shops. It had four cylinders (3 3/8-inch bore, 5 1/2-inch stroke) with 197-cubic inch displacement and developed 43 horsepower at 2100 rpm. Its overhead valves led the engine to be called the "Templar Vitalic Top-Valve Motor." The valves were enclosed in an aluminum case. An article in Horseless Age said: "It was this remarkable motor that inspired the Templar ideals and enterprise." The engine was said to be smooth running despite its having only the four cylinders and was held to be more efficient than the engines in most American cars of that day. The power was transmitted through open Hotchkiss drive, not through a torque tube as on most American cars. The wheelbase measured 118 inches. The springs were semi-elliptical. The rear axle was the semi-floating type. The initial models included four- and five-passenger touring cars priced at $1,985, the four-passenger Victoria elite at $2,155, and a two-passenger roadster at $2,255--all built on the same chassis. The bodies were given twenty-seven coats of paint. Standard color options were Valentine red, Tiffany bronze, light wine and Allegheny blue, with fenders, chassis, and splashguards in black enamel. Wheels were natural finish woods. Striping and monograms or initials were extra. In addition to the standard body styles, the company announced it would furnish estimates on special enclosed bodies, built to individual specifications under Templar supervision in the shops of Cleveland specialists Lang or Rubay. One of the features of the Templar was its array of equipment--a host of accessories, which, if available at all, were "extras" on most cars. Probably the most unique of these were a folding Kodak camera and a compass, which could be neatly tucked away in their own single compartment in the side of the Templar's body. With the five-passenger touring and the four-passenger sportette, additional standard equipment included an inspection light and cord (powered from the car's battery), an electric horn, a tire pump and hose which operated from the engine, a tire pressure gauge, a clinometer (grade indicator), a muffler cutout, a keyless rim-winding clock, a spotlight, a dash light, a lock on the ignition switch, a motometer, a windshield cleaner (oscillating wiper), a one-man Never-Leek top with side curtains that opened with the doors, and a plate-glass rear window, plus a complete tool kit with jacks. The car came with a spare wheel rim, but in spite of all the other equipment, without a fifth tire. The new Templar was exhibited at the automobile shows in New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and Cleveland in early 1918. Later in the year the price for either of the above-described five-passenger touring and four-passenger sportette models was raised $100 to $2,085. For the two-passenger touring roadster, the price was increased $130 to $2,385. Templar adopted the slogan. "The Superfine Small Car." A 1918 ad for the two-passenger sport roadster said in part: "Those men of affairs, who like to do their own driving, are extravagant in their praise of this superlatively high-grade car. It is as serviceable as its originality is distinctive. It gives that complete satisfaction formerly associated with the extravagantly priced, cumbersomely built big machines. And its small size makes it a car of much greater convenience. There is no previous standard of design, or agile, economical performance by which to compare it." It was that model, the two-passenger roadster, which was considered the standout of the Templar line. Its standard equipment included the camera, the compass, and an aluminum step (in place of a running board) on either side. Also included were six wire wheels, all with tires and tubes, the two spares being stored in a rear deck well. Standard color options were the same as on the other models, plus khaki gray, and the fenders, chassis, and splashguards were painted the same color as the body. Upholstery options included red or black leather; the wire wheels were available in red, white, or black, the latter being furnished unless one of the others was specified. Added to the line was a five-passenger sedan with a price tag of $3,285 f.o.b. Cleveland. Production for 1918 totaled about 150 cars. By late January 1919, steady production of automobiles was resumed, and by the end of that year some 1,800 units had been turned out. More manufacturing area was needed in addition to the nearly six acres of floor space already under roof. M. F. Bramley, Templar president, directed construction of five new buildings costing $1,000,000. Prices continued to increase: for the touring, sportette, and roadster, as of December 15, 1919, they rose to $2,685, for the sedan, to $3,585. In early 1920 the company was reorganized as the Templar Motors Company, inc., with $10,000,000 authorized capitalization. A few weeks later it filed suit against the Standard Parts Company for $1,400,000 for alleged breach of contract in failing to deliver 10,000 axles. (One is reminded of difficulties of obtaining new cars and their parts in America in the first year or so after World War II, when cars were delivered to an impatient public minus bumpers, many without rear seats and numerous items of interior and exterior trim.) The June 1920, financial statement of Templar showed total assets of more than $9,500,000 and liabilities of less than $750,000. The company paid quarterly dividends. There were 106 sales places and distributor centers in thirty-two states and fifteen foreign countries. Earl Martin, formerly with the Curtiss Aeroplane Company and later with the Rubay Company, was made Templar's manager. Charles E. Taylor, formerly with Royal Tourist, Peerless, Chalmers, and Hal Twelve automobile companies, was in charge of factory production. In July 1919, the famous racing driver. E. G. "Cannonball" Baker set a New World's record driving from New York to Chicago in a Templar. His time of twenty-six hours and fifty minutes was six hours and ten minutes faster than the previous record and was accomplished through 230 miles of rain, 200 miles of fog and 110 miles of mud detours, a total of 992 miles at an average speed of 36.97 miles per hour. A combination of the post-war depression and the difficulty in getting parts and supplies (and many of those contracted for at wartime prices) left business for Templar somewhat erratic. In late autumn, 1920, a stockholder filed court application for appointment of receiver for the company, alleging fraud, deceit, and mismanagement. After a hearing, the judge branded the application and the attack back of it just as serious a moral crime as causing a run on a bank. There had been stormy stockholders' meetings in Columbus and Cleveland denouncing the management, but ending, nevertheless, in a vote of confidence in the officers. Templar's production for 1920 was some 1,850 units, which ranked sixth in Cleveland and fifteenth in the United States among automobile manufacturers outside the Detroit area. But the post-war depression was sorely felt. From September 1920, to March 1921, sales totaled 128 cars, Bramley told stockholders' meeting. The work force was down to 165 from a normal number of about 900. Effective July 1, 1921, price cuts of $500 were announced on Templar's open models and $600 on the closed. New prices thus were $2,385 for the two-, four-, and five-passenger touring cars, and $3,185 for the sedan coupe. Less than three months later they were lowered again, by an additional $400, to $1,985 and $2,785, respectively. Beginning in 1919 the Templar Company published a promotional newssheet called Templar Topics; of full-size newspaper format, it consisted of four pages. An article in the December 1921, issue told of a novel plan that had been used by the company the previous summer to exhibit its new roadsters. In July, "Cannonball" Baker had embarked on a 7,300-mile trip convoying three roadsters to introduce them to dealers. Baker led the procession driving the "Recruiter," a Templar stock car that he had made famous in 1920 when he broke several transcontinental records while carrying U.S. Army messages between the Atlantic and the Pacific and from Mexico to Canada. The car had also featured in the aforementioned New York-Chicago trek in 1919. Accompanying Baker in the new roadsters were Arthur Halliday, "mechanician," and other company representatives. In addition to visiting every Templar dealer east of the Mississippi River, Baker challenged any comer to a contest of speed, economy, or durability with any stock, foreign, or American-built car. But he had no takers. The article continued: "A few years ago Baker made a certain well known make of motorcycle famous by his own remarkable power of endurance and nerve, BUT HE HAS BEATEN EVERY ONE OF HIS OWN MOTORCYCLE RECORDS WITH THE TEMPLAR . . .." On October 14, 1921, Baker, driving the "Recruiter", set a new record for a run from Akron to Cleveland--twenty-five minutes and twenty-six seconds, at times exceeding speeds of seventy-five miles an hour and averaging over a mile a minute. An article in Templar Topics recounting the feat said: "The route, via Brecksville and Independence, is very dangerous, including 63 hills and valleys, 45 turns, five railroad crossings, four bridges, two bad road breaks where it is necessary to straddle, taking part dirt and part paving, and through six towns." Two Cleveland newspaper reporters and two observers of the American Automobile Association witnessed the event. The starting and arriving times were checked by the AAA." Besides its line of private passenger cars, Templar also produced some taxicabs. The Checker Taxi Company of Chicago had about 100 in use by late 1921, and the Waite Taxicab & Livery Company, Cleveland, added twelve Templar taxis to its feet. As year's end approached, the Templar's economic recovery seemed assured, with some 850 units having been produced in the twelve-month period. But then came a new blow to the manufacturing operation when fire swept a major section of the Templar plant on the night of December 13. 1921. The loss was estimated between $250,000 and $300,000. The original main plant, built in 1917 was destroyed, along with thirty automobiles and a stock of various parts and supplies. Though only the main, fireproof plant remained, manufacturing of automobiles was resumed a few days later. Undaunted, the company continued production of cars--a complete line of open and closed-body, four-cylinder models. By April 1922, Templars were turned out at a rate of eight a day, though the plant's assembly line had a capacity of twenty-five a day, a potential of more than 5,000 a year. A new four-passenger coupe selling for $2,650 was added to the Templar line in August. The coupe had a luggage compartment behind the cab, with a hinged deck lid. However, the controversy between a group of stockholders and the Templar management persisted, and the company was having trouble remaining solvent. On application of the U.S. Axle Company of Pottstown, Pennsylvania, which claimed its bill of $12,500 against Templar was overdue, a federal judge in Cleveland placed the automobile company in receivership in October, 1922. T L Hausmann, formerly an assistant to Templar's president Bramley was named receiver. Nonetheless the company continued to make and ship new cars daily. Hausmann obtained several new contracts and again it appeared the Templar might succeed. Through early 1923, production was at a rate of about one car a day. By autumn, 1923, the company was reorganized as the Templar Motor Car Company with Hausmann the head. It continued the former line of four-cylinder models and added a new line of six-cylinder (3 3/8-inch bore. 5-inch stroke) Templars having four-wheel brakes. Horsepower was rated (by the older method) at 27.34 compared to the 18.23 of the four-cylinder models. Also, the wheelbase, at 122 inches was four inches longer, all of which took the larger Templar out of its original "small-car'' class, though the price of the Six ranging from $1,895 to $2,595 depending on body styles was not much higher than that for the smaller Templars. But success still eluded the Templar. In autumn, 1924 a Cleveland bank took over the company for default of payment of a loan. The Templar automobile was through. In all, some 6,000 cars were made between 1917 and 1924. More than $6,000,000 was lost by approximately 20,000 investors in the failure of the Templar motor car. And though production terminated, even more trouble stalked the Templar. The sale of uncertified securities, investigated by the Ohio Securities Commission in early 1925, led to indictments of a group of men charging them with violations of the Ohio blue sky laws. Two who had been fiscal agents of Templar were acquitted; nine salesmen whom they had employed pleaded guilty and were fined. In 1920 it began hurting badly from the post-World War I depression, difficulty in obtaining parts and growing competition from other carmakers. Henry Ford, for example, at times sold his "Tin Lizzie" Model T for less than $300. Then, on Dec. 13, 1921, a fire broke out, and only the main fireproof building that remains today withstood the blaze. Damage loss, estimated between $250,000 and $300,000, doesn't appear particularly great by today's standards but was crippling 67 years ago. Although Templar rebounded and was producing at a rate of eight cars a day by April 1922, more problems surfaced. Severe financial losses as well as stockholder controversies soon beset the company. Finally, in the fall of 1924, Templar defaulted on payment of a substantial loan and was taken over by a Cleveland bank. Production halted and failure of the company caused about 20,000 investors to lose a total of $6 million, a sum that today, with the effects of inflation, would amount to more than $42 million. History from Lake Erie Screw Company and OldCompany.com.

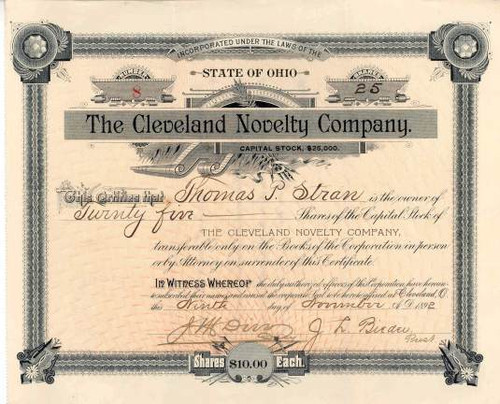

Certificate