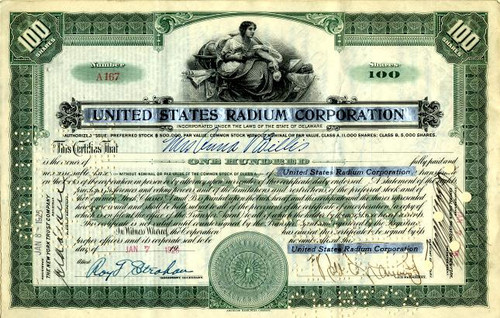

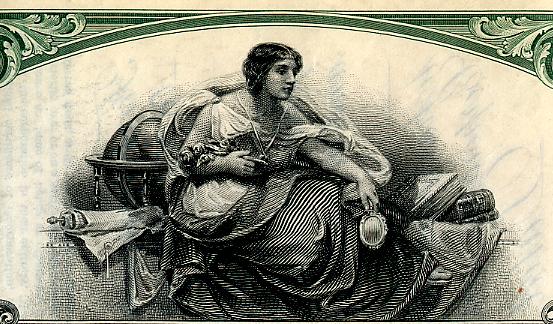

Beautifully engraved RARE certificate from the United States Radium Company This historic document was printed by the American Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of an allegorical woman sitting next to a globe and books. This item has the signatures of the Company's Vice President and Secretary, Roy t. Strahan and is over 98 years old. The certificate was issued to George Willis, co founder, and signed by him on the verso.

Certificate Vignette

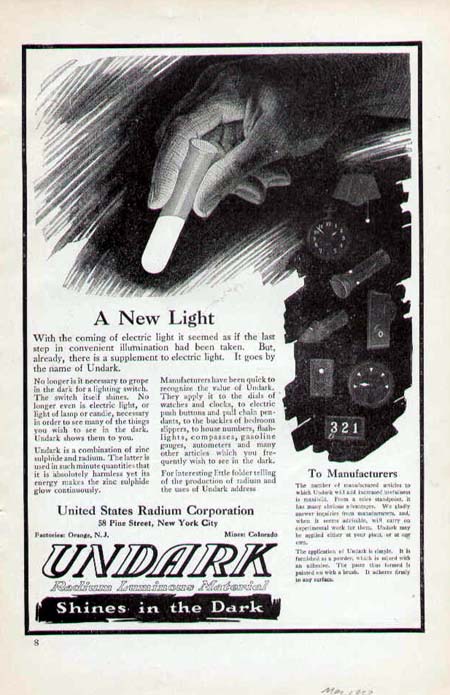

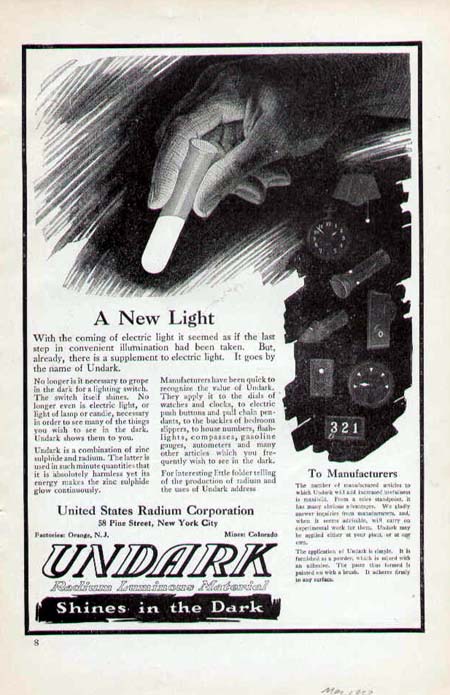

United States Radium Company Ad shown for Illustrative Purposes Radium-226 is an alpha emitter with a 1600 year half-life. It emits a gamma ray at 186 keV. Radium decays into a number of short lived decay products that can usually be expected to be present at, or close to, the same activity as the radium. These decay products (Rn-222, Po-218, Pb-214, Bi-214, Po-214, Pb-210, Bi-210, and Po-210) emit alphas, betas and gamma rays. By itself, radium in high enough concentrations will glow blue, a phenomenon first observed by Marie and Pierre Curie. That the radiation emitted by radium would cause various materials , such as zinc sulfide, to fluoresce was first recognized by Henri Becquerel. The invention of radioluminescent paint can be attributed to William J Hammer who mixed radium with zinc sulfide (in 1902), and applied the paint to various items including watches and clock dials. In a case of bad judgment, he failed to patent the idea. Recognizing a good opportunity, a gemologist at Tiffany & Company, by the name of George Kunz, did patent it. Kunz and Charles Baskerville, a chemist, made their paint by mixing radium-barium carbonate with zinc sulfide and linseed oil. At that time, at least in the US, radioluminescent paint saw little application. It stayed in the bottle. But in Europe, especially Switzerland, things were different. Quoting Ross Mullner "there were so many radium painters in that country that it was common to recognize them on the streets even on the darkest nights because of the glow around them: their hair sparkled almost like a halo." In the US, the first company to produce radioluminescent paint was the Radium Luminous Material Corporation in Newark New Jersey (Changed their name to United States Radium Company in 1922). It was founded in 1914 by Sabin von Sochocky and George Willis, both physicians. Their operations expanded tremendously when the United States entered World War I, and in 1917 they moved from Newark to Orange, New Jersey. They also got into the business of mining and producing radium. In 1921, they changed their name to the U.S. Radium Corporation. The brand name for the radioluminescent paint produced by US Radium Corporation was "Undark." Standard Chemical Company used the name "Luna" and the Cold Light Manufacturing Company, a subsidiary of the Radium Company of Colorado, made "Marvelite." According to NCRP Report No. 95, radium has not been used in radioluminescent watches since 1968, or in clocks since 1978 (these dates are approximate). Radium Dial Painters During the 1920s, the radium paint was applied to clock and watch components in a variety of ways: painting it on with a brush, painting it with a pen or stylus, applying it with a mechanical press, and dusting. The latter procedure involved dusting a freshly painted dial with radioluminescent powder so that the powder would stick to the paint. The original practice of using the mouth to put a point on a brush is described as follows by Robley Evans: "In painting the numerals on a fine watch, for example, an effort to duplicate the shaded script numeral of a professional penman was made. The 2, 3, 6, and 8 were hardest to make correctly, for the fine lines which contrast with the heavy strokes in these numerals were usually too broad, even with the use of the finest, clipped brushes. To rectify these broad parts the brush was cleaned and then drawn along the line like an eraser to remove the excess paint. For wiping and tipping the brush the workers found that that either a cloth or their fingers were too harsh, but by wiping the brush clean between their lips the proper erasing point could be obtained. This led to the so-called practice of "tipping" or pointing the brush in the lips. In some plants the brush was also tipped before painting a numeral. The paint so wiped off the brush was swallowed." It might be worth noting that tipping the brushes was not something the dial painters just decided to do. At least in some plants they were actually trained how to do it. In fact, the instructors sometimes swallowed some of the paint to show it was harmless. It has been estimated that a dial painter would ingest a few hundred to a few thousand microcuries of radium per year. While most of the ingested radium would pass through the body, some fraction of it would be absorbed and accumulate in the skeleton. Later on, Robley Evans would establish a maximum permissible body burden for radium of 0.1 uCi. As a result of the ingestion of the radium, many of the dial painters developed medical problems of varying degrees of severity. The first deaths occurred in the mid 1920s, and by 1926 the practice of tipping the brushes seems to have ended. The Radium Girls was the name given to women subjected to radiation exposure at the United States Radium Corporation factory, in Orange, New Jersey, beginning during World War I, five of whom gained notoriety for their efforts in challenging their employer in court. The five women, and many of their co-workers and radium paint plant workers from across North America, died from radiation exposure during the course of the litigation. U.S. Radium Corporation From 1917 to 1926, U.S. Radium Corporation was engaged in the extraction and purification of radium from carnotite ore to produce luminous paints, which were produced under the brand name 'Undark'. As a defense contractor, U.S. Radium was a major supplier of radioluminescent watches to the military. Their plant in New Jersey employed over a hundred workers, mainly women, to paint radium-lit watch faces and instruments. Radiation exposure The Radium Girls saga holds an important place in the history of both the progression of the field of health physics and of the labor rights movement. The U.S. Radium Corporation hired some 70 women to perform various tasks including the handling of radium, while the owners and their scientists -- familiar with the effects of radium -- carefully avoided any exposure to themselves; chemists at the plant used lead screens, masks and tongs. An estimated 4,000 workers were hired by corporations in the US and Canada to paint watch faces with radium. For fun, the Radium Girls painted their nails, teeth and faces with the deadly paint produced at the factory, sometimes to surprise their boyfriends when the lights went out. They mixed glue, water and radium powder, and then used camel hair brushes to apply the glowing paint onto dial numbers. The going rate, for painting 250 dials a day, was about a penny and a half per dial. The brushes would lose shape after a few strokes, so the U.S. Radium supervisors encouraged their workers to point the brushes with their lips, or use their tongues to keep them sharp. Radiation sickness Many of the women later began to suffer from anemia, bone fractures and necrosis of the jaw. Primitive x-ray cameras bombarded some of the sickened workers with additional radiation when they sought medical attention for the many ailments that ensued. It turned out at least one of the examinations was a ruse, part of a campaign of disinformation started by the defence contractor. U.S. Radium, like other watch-dial companies, rejected claims that the afflicted workers were suffering from exposure to radium. For some time, doctors, dentists and researchers complied with requests from the companies not to release their data. At the urging of the companies, worker deaths were attributed by medical professionals to other causes; syphilis was often cited in attempts to smear the reputations of the women. Litigation The story of the labor abuse perpetrated against the workers is distinguished from most such cases by the fact the ensuing litigation was covered widely by the media. Plant worker Grace Fryer decided to sue, but it took two years for her to simply find a lawyer willing to risk taking on U.S. Radium. A total of five factory workers, dubbed the Radium Girls, joined the suit. The litigation and media sensation surrounding the case was notable from a historical perspective, for it established legal precedents and triggered the enactment of regulations governing labor safety standards, including a baseline of 'provable suffering'. Historical impact The right of individual workers to sue for damages from corporations due to labor abuse was established as a result of the Radium Girls case (though the combined settlement for the Radium Girls was only $10,000). In the wake of the case, industrial safety standards were demonstrably enhanced for many decades. The case led to passage of a congressional bill, in 1949, which made all occupational diseases compensable, and extended the time during which workers could discover illnesses and make a claim. Literature The story of the workers was immortalized in the poem "Radium Girls" by Eleanor Swanson, and is included in her collection, A Thousand Bonds: Marie Curie and the Discovery of Radium (2003). Writer D.W. Gregory also reincarnated the story of Grace Fryer through her award-winning play Radium Girls, which premiered in 2000 at the Playwrights Theatre of New Jersey in Madison, New Jersey. History from Wikipeida and OldCompanyResearch.com.

Certificate Vignette

United States Radium Company Ad shown for Illustrative Purposes