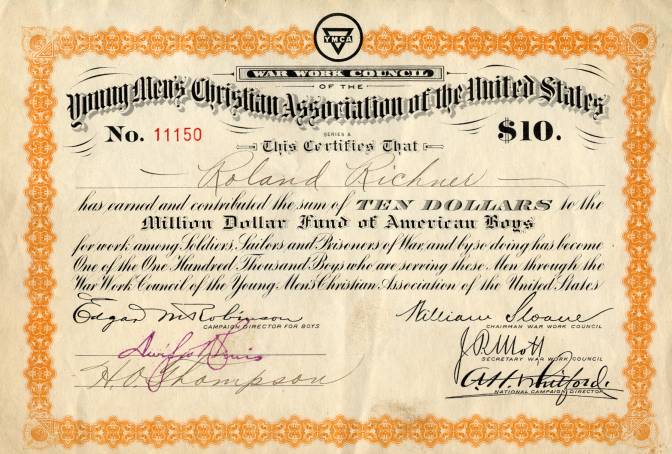

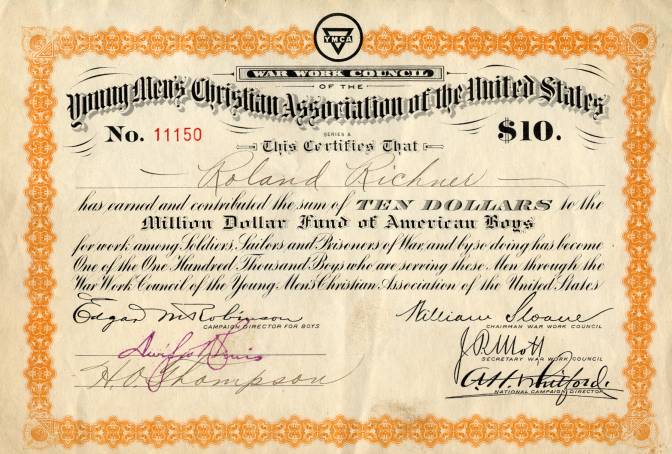

Beautiful $10 Contribution Certificate from the War Work Council of the Young Men's Christian Association of the United States This historic document has an ornate border around it with a vignette of the YMCA Logo. This item has the printed signatures of the Chairman, Secretary, Campaign Director, and National Campaign Director. Old 6 by 9 inch certificate from the YMCA War Work Council, certifies that Roland Richner has earned and contributed the sum of ten dollars to the Million Dollar Fund of American Boys. WWI era.

Certificate When the U.S. entered World War I, the YWCA joined the "Committee of Eleven" organizations that banded together as the United War Work Campaign, Inc., to raise and distribute funds to aid war relief efforts at home and abroad. (Though the group originally included eleven organizations, that number eventually settled at seven, including the American Library Association, YMCA, YWCA, National Catholic War Council, Knights of Columbus, Jewish Welfare Board, Salvation Army, and War Camp Community Service.) As the only women's organization in the Campaign, the YWCA's charge was to meet the special needs of women and girls affected by the war. The YWCA raised money, recruited war workers, expanded its existing work in places which already had YWCAs and constructed new facilities in other places, such as camps and bases where soldiers were mobilized and centers where young women were mobilized for agricultural, industrial, and government work. The War Work Council established Industrial War Service Centers or "blue triangle" houses in the U.S. and Foyers des Allees in France where women working in war industries could meet, get good food, relax, entertain guests and participate in wholesome recreation. It also built Hostess Houses where servicemen could visit with their wives, mothers, and friends. Work in these centers continued through the period of active conflict, and the following influenza epidemic and demobilization. Due to the perceived inappropriateness of white women providing recreational services for Black servicemen and industrial women, the YWCA established separate "colored" Industrial Service Centers and Hostess Houses. The was "made evident the deplorable lack of facilities for recreation and amusement" of African-American women and girls who were entering industry in large numbers. In response, the National Association facilitated a substantial expansion of the number of "Colored" Associations and Branches in cities. This dramatic increase of staff and program for African-Americans, was directed from the national office by Eva Bowles and the War Work Council's Colored Work Committee. A national staff which had consisted of two Black secretaries in 1917, grew to thirteen in 1919. At the local level, the number of "Colored" Branches increased from sixteen to forty-nine and secretaries from nine to ninety-nine. World War I precipitated a significant increase in both the size and complexity of the national program of "Work with Foreign-Born Women." The war changed American attitudes toward its immigrant population, suddenly making "every foreign home a place of dread and fear and suspicion." (Edith Terry Bremer, Report to War Work Council, 17 October 1917) Noting that the effects of the war were even more severe for foreign-born women, what had been essentially a northeastern U.S. operation, was nationalized. Multi-lingual secretaries were hired for Port Work, meeting immigrant women at points of intake on the east and west coasts. Staff of a new International Information and Service Bureau translated all kinds of technical materials and wrote speeches and information sheets in a variety of languages "upon all matters for which they are needing help." Other secretaries did Emergency Field work to help speed the opening of new International Institutes for young women of all nationalities. A Bureau was established to help in locating refugee relatives in Europe and the YWCA provided "home service" for the families of enlisted men. To facilitate all this new work and reconstruction work in Europe, the YWCA established training programs for foreign community workers and reconstruction volunteers. Other War Work Council Committees coordinated programs to find housing for women workers who had left home to work at camps and in industry, for women agricultural workers, and for matching volunteer workers with jobs. The Committee on Organization and Extension of Regular Work analyzed where special war work could connected with the regular city work. Staff specialists in topics such as Recreation and Pageantry and Drama, helped Community Associations develop classes and activities for relaxation during uncertain times. The YWCA's Bureau of Social Morality, formed in 1913, was a corps of women medical doctors trained to give sex education lectures. Concerned in particular about young women in the communities adjacent to army camps, the YWCA recruited and trained many more speakers who delivered over 2,000 lectures in 1917-18. During reconstruction, the YWCA enlarged the Bureau's mission to include lectures on general health topics, such as nutrition and hygiene, and rechristened it the Bureau of Social Education. The U.S. YWCA did similar work overseas during the war in Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Italy, the Near East, Poland, Romania, and Russia. War workers established centers "to help keep women fit for their work" by providing opportunities for rest, relaxation, and a good meal at a reasonable price. A special group of "Polish Gray Samaritans" served as nurses' aides for Polish soldiers fighting in France. Once the war was over the focus of the work shifted to reconstruction and aid for refugees. The "Polish Grays" concentrated their efforts in Poland. After the Armistice, the Continuation Committee (1919-22) and the Post-Continuation Committee (1921-22) kept much of the work begun by the War Work Council going using War Fund money. The rapid expansion of the War Work significantly changed the YWCA. It experienced what was described as fifteen years' growth in two. Many new Community Associations and Branches were formed and the existing emphasis of the work in many Associations changed, particularly in response to the influx of Industrial Club members. With the new members came increased expectations of "democratic control of Association policies and program." At the national level, the rapid increase put a huge emphasis on recruitment and training of staff, greatly increased the use of publications to "interpret" the Association, and dramatically broadened its program, both in size and scope. Sustaining such an organization proved impossible once the war was over. The War Work had such a major impact on the work of YWCA that the records are central to understanding the growth and development of the organization. The wide-ranging effects can be seen in the kinds of work the Association did, its techniques, processes, policies, and even its size. History from the Five College Archives & Manuscript Collection.

Certificate