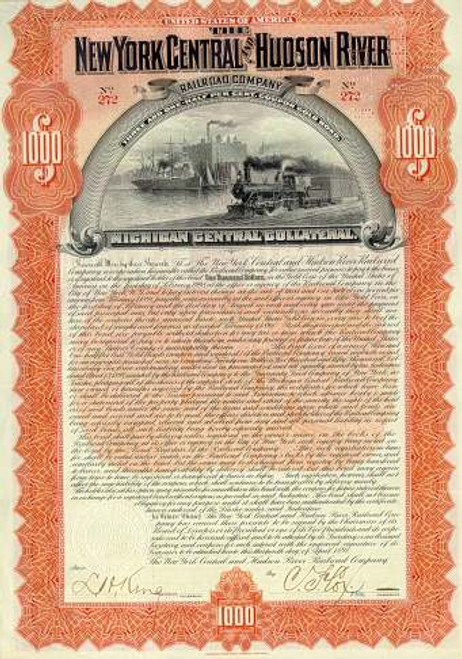

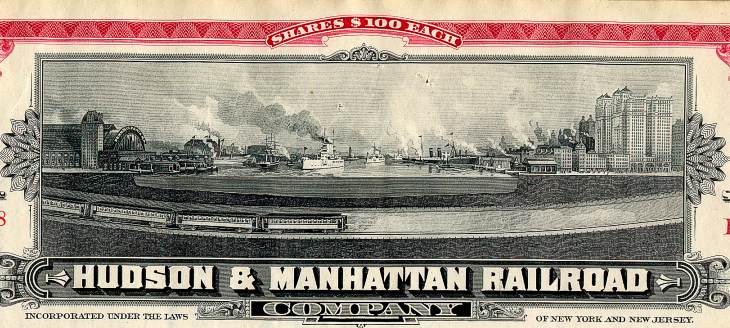

Beautifully engraved and getting difficult to find certificate from the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Company issued no later than 1935. This historic document was printed by the American Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of a cross sectional view of the Great White Fleet steaming down the Hudson River as a train crosses below. This item is hand signed by the company's vice-president and treasurer and is over 75 years old.

Certificate Vignette The idea of building a tunnel under the Hudson River was conceived in the 1860s as lower Manhattan became heavily congested. The belief was that with a tunnel under the Hudson, the railroad lines terminating on the west shore of the river could run their trains directly into the city, making it possible for people to live comfortably in suburban New Jersey and commute into the City. The first person to actually begin building the tunnel was DeWitt Haskins, who organized the Hudson Tunnel Railroad Company. With $10,000,000 of capital stock issued, he began to build a tunnel between 15th Street and the New Jersey shore. However, in 1874 the Lackawanna Railroad obtained an injunction to halt work because of the competition which the new line would give to the railroad's ferries. In 1879 work resumed but was soon halted again after a blowout occurred, taking 20 lives. In 1889 work was begun again by the English firm of S. S. Pearson and Son, but financial woes plagued the supervising Hudson Tunnel Railroad Company, then headed by John R. Dos Passos, and in 1892 work was suspended again. In 1889, an ambitious young lawyer, William G. McAdoo, independently thought of a plan to build a tunnel under the Hudson. Mr. McAdoo thought that running electric trains in tubes under the river would be the most feasible answer to problems faced by late 19th century commuters plagued by slow ferries running on long headways. He had previously had experience with railroad electrification. While practicing law in Chattanooga, Tennessee, he became trustee of the Knoxville Street Railroad. Because of his persuasive powers, money was borrowed to electrify the Knoxville horsecar lines in 1890. To personally supervise the undertaking, Mr. McAdoo commuted almost daily between the two cities-a distance of 120 miles. William Gibbs McAdoo Mr. McAdoo moved to New York in 1892. He became a business associate of John Dos Passos, a leading corporation lawyer and president of the defunct Hudson Tunnel Railroad Company. Obsessed with the tunnel idea, McAdoo mentioned his proposal to Dos Passos, who informed him of the abandoned half-mile segment of tube lying under the river. Through Dos Passos McAdoo was introduced to Charles Jacobs, who was the engineer in charge of the abandoned work. Jacobs, and his firm partner, J. Vipond Davies, estimated that completion of the tunnel would cost four million dollars. Upon inspection of the pumped-out tunnel, McAdoo and the engineers found that the basic structure and equipment were usable. By the selling of bonds by the Hudson Companies, money was provided to continue the construction of the tunnel. At this time, McAdoo was president of the New York and New Jersey Railroad Company-one of several companies interested in securing a franchise on the portion of the proposed line to be built in Manhattan from the New York Rapid Transit Board. Later, the company and others with the same interest combined, forming the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company, and Mr. McAdoo became president of what for many years was to be known as the "H&M". The Hudson Companies began work in 1902 under the river, with the agreement that the firm would turn the tunnels over to Mr. McAdoo to operate upon completion. The tunnel was built by pushing a shield through the silt at the bottom of the river. As the mechanical shield was pushed through the mud, every thirty inches the door was opened and the displaced mud placed into the chamber, where it was shoveled into small cars which hauled it to the surface. In places the silt was baked with huge kerosene torches to harden it so it would be removed more easily. When the company began the second uptown tube, enormous hydraulic jacks pushed a shield through the mud at the rate of seventy-two feet a day. Mr. McAdoo states in his autobiography, Crowded Years, that this was the first time in history that a tunnel was bored without laborers having to excavate and remove the displaced earth. All of the work was done under an air pressure of thirty-eight pounds per square inch. However, the tunnel engineers ran into difficulty when a reef was encountered on the Manhattan side of the river. Chief Engineer Jacobs devised a method of dynamiting through the reef and removing the rock through the doors of the bulkhead. Clay was dumped onto the reef from barges to lessen the chance of a tunnel blowout occurring. Several blowouts did occur, nevertheless, and the worst one took one man's life. In this accident three canvas yacht sails were fastened together to plug the leak, However, when the interior of the bulkhead was reopened, the sails, as well as the clay weighing them down, were sucked into the tunnel. Mr. McAdoo intended that the uptown line be modern and efficient in every respect. The terminals at Hoboken and 33rd Street were built so that passengers arriving aboard the trains would be discharged onto one platform, and on the other side would be the loading platform. The stations were characterized by vaulted arches, round classical pillars, and wide passageways leading to the surface. He observed the mistakes in the construction and operation of New York City's Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) subway, and eliminated the possibility of these flaws in his line. He particularly desired to eliminate the conflict between people boarding the cars and those leaving; hence the separate platforms. No stations were located on curves. Each subway platform was 370 feet long, long enough to hold an eight-car train. The river tubes were 5,650 feet long between shafts and reached a maximum depth of 97 feet below mean sea level. The diameter of the tubes was 15 feet, three inches and they were thirty to eighty feet apart under the river. Plaque honoring President Roosevelt's ceremonial opening of the H&M tubes Mr. McAdoo also incorporated novel ideas into the design of the cars for the Uptown Division, which were custom-manufactured by the American Car and Foundry Company and the Pressed Steel Car Company. Instead of holding onto straps, passengers could steady themselves by holding onto poles running between the car floors and ceilings. The center door of each car was opened pneumatically, and each car had a concrete floor to prevent passengers from slipping. Finally, each car was constructed entirely of steel, unlike those of the gloomy city subway. The first tube was "holed through" on March 11, 1904. Mr. McAdoo was called urgently from his desk by Chief Engineer Jacobs when the two shields met, and he, followed by a procession led by Jacobs, walked from New Jersey via the tube, through the doors of the two shields, to New York. The mate tube was holed through on September 24, 1905. As public interest in the project continued to rise, and as work progressed on the tubes and the cut and cover excavation along Sixth Avenue in New York City, Mr. McAdoo was planning possible extensions to the Tubes. One would have run from the 9th Street Station to Astor Place, offering IRT passengers an across-the-platform transfer to the H&M. The 6th Avenue line was to be extended to Grand Central Station. Construction was started on the line to Astor Place, but only about two hundred and fifty feet of the line were completed before Mr. McAdoo decided to stop construction of this branch until the most important extension of all was completed-a line linking the Erie Terminal with the Pennsylvania Terminal at Exchange Place, and Cortlandt Street in Manhattan. The west end of the Summit Avenue (now Journal Square), Jersey City station of the H&M, 1911. While construction continued, the Hudson Companies' Board of Directors was being increased by some of the wealthiest men in New York. Mr. McAdoo, whose chief role as head of the H&M was the promotion of the tunnels, persuaded Pliny Fisk, Cornelius Vanderbilt, J. P. Morgan and others to invest money in the building of the Tubes. A total of over seventy million dollars was raised and spent on the seventeen miles of tunnel. The years 1906 and 1907 saw the completion of the uptown stations between Christopher Street and 19th Street, the arrival of equipment (delivered after testing on New York's Second Avenue Elevated Line), and the start of construction on the downtown tunnels. Two tubes were being tunneled between Exchange Place and the new Hudson Terminal at Cortlandt, Church and Fulton Streets. The Hudson Terminal was to consist of a station area topped by two 22-story buildings housing the H&M offices and with enough spare office space to hold 10,000 other people. Mr. McAdoo predicted that these two buildings would stimulate a great increase in traffic between New Jersey and the downtown Manhattan area. The Hudson Companies spent the first two months of 1908 testing the trains on the Second Avenue Elevated, and running them through the Tubes loaded with enough sandbags to equal the weight of a full load of passengers. The companies also ran several inspection trips for the press, and on the morning before the opening, a special train was sent from Manhattan to Hoboken loaded with a special "Tunnel Edition" published by the Jersey City Journal. The alert Mr. McAdoo had the H&M's public relations department send press releases to large newspapers across the country describing the now-famous Tubes. When not involved in promotion work, Mr. McAdoo was personally supervising the construction work under the Hudson or at the downtown terminal. He climbed onto a steel beam which was about to be hoisted to the top of the structure, and was lifted 275 feet into the air, while closely surveying the structure. The workers at the top of the building were aghast, but Mr. McAdoo just smiled and said "Good Morning, Gentlemen." Artist's rendering of the proposed Journal Square station with yard, PRR steam tracks, and trolley loop. It was not constructed this way. Mr. McAdoo insisted upon only the best treatment for the expected thousands of people who would be riding the H&M. Just before the gaiety of the opening day celebration exploded in Hoboken, Mr. McAdoo gathered his employees together in one of the stations and outlined his reactionary policy for running a transit system-a policy which, while making him a hero in the eyes of the public and the press, was never followed as closely by any other railroad in the United States. He began quietly by pointing out that "the employees are the people upon whom the success of the railroad depends. This railroad was not," he continued, "built for the stockholders, for its officers, or for its employees; it was built for the public. Its first consideration must always be the safety, comfort, and convenience of its patrons. Any railroad employee who adopts the attitude of other railroad corporations, 'the public be damned,' will get into trouble. Employees must always give civil answers even when the questions asked are silly. For years the elevated lines... have been telling their passengers 'to step lively'; any H&M man saying that or using any similar terminology will be fired." Mr. McAdoo's policy of "the public be pleased" was a tremendous factor in his personal success in running the H&M, and was the primary factor in the popularity of the line. His talk was greeted by cheers and applause, showing that the H&M's president and his employees understood and respected each other. The term "the public be pleased" became the motto of the H&M. It was the direct opposite both in statement and attitude of a comment made by the son of William Vanderbilt, many years before, regarding the passenger service of the New York Central Railroad. At 3:30 on the afternoon of February 25, 1908, a long line of invited dignitaries entered the 19th Street Station for the first official run through the Tubes. The station and eight-car train were in darkness, except for emergency lights operated from storage batteries in the train. Standing by in the station was a special telegraph operator, who signalled President Theodore Roosevelt, waiting at his desk in the White House, to push a button turning on the power. As the President turned on the current, the station and train were immediately flooded with light and the chattering of the compressors mingled with the cheers of the 400 guests. As the train swiftly picked up speed, in Mr. McAdoo's words, "the silk-hatted gentlemen sat in rows, leaning on their canes, and looking a little uneasy as they glanced out of the windows and saw the curving iron walls flash by." The boundary line between the states was marked by a circle of red, white and blue lights in the tube, and the train stopped here to allow New York Governor Charles Hughes and New Jersey Governor Franklin Fort to shake hands between the two cars, symbolizing the "formal marriage of the two states." When the train arrived at Hoboken, almost 20,000 cheering people were thronging in the square outside the terminal, and as the official party came out of the kiosks, boats in the harbor and church bells added to the din. Following speeches by Mr. McAdoo, the two governors, and other officials, Mr. Oakman, president of the Hudson Companies, turned the property over to Mr. McAdoo, for operation by the H&M. Then the official party returned via the Tubes to Manhattan for an elaborate banquet at Sherry's. H&M timetable showing route map and connecting services. The line opened at midnight, operating on a five-minute headway. The sky over Hoboken was punctuated with fireworks as over 5,000 people waited to be admitted into the station. When the first regular passenger train left Hoboken, it was packed with cheering, singing people, including a large group of Yale students, who were toasting the line with drinks. The platforms of the Manhattan stations were also mobbed despite the late hour. In the first 24 hours, over 50,000 people rode the line. The morning rush hours saw a virtual abandonment of the Lackawanna's ferries, as the commuters availed themselves of the H&M's three-minute headway and eight-minute running time to 19th Street. The opening was front page news in the New York press. The Times cited the event as "one of the greatest engineering feats ever accomplished, greater perhaps than the Panama Canal will be when opened, considering the obstacles which had to be overcome." The Sixth Avenue stores seized the opportunity to exhibit merchandise in the display windows in the stations under Sixth Avenue. All stations were entered through neighboring stores; no sidewalk entrances were built. Sales boomed, as did real estate values along the Lackawanna's line, when thousands of people moved from the City to New Jersey suburbs. The crossover west of 9th Street on the uptown branch in a 1907 photo. It was removed in 1910. The line was extended to 23rd Street on June 10, 1908. Trains used only the easterly track to reach 23rd Street, crossing over to the westbound track on the return trip at 19th Street. Before the opening of the downtown tubes, Mr. McAdoo went to the office of Alexander J. Cassett, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, to ask him to abandon the ferry service from the PRR Exchange Place Terminal to Manhattan, so that passengers would be channeled into the H&M. He argued that the Tube trains would be faster and more appealing to the passengers. Mr. Cassett was most impressed with Mr. McAdoo's manner. The ferries were not taken off, but they were renovated to handle vehicular traffic more easily. In addition, PRR tickets were to be accepted on the H&M for passengers who wished to continue to Manhattan via the Tubes. The Downtown Tunnels The downtown river tunnels, on the other hand, came no closer than 90 feet and at the state line are 240 feet apart. They were built through mud and rock at a depth of 60 to 90 feet below mean low water level, and were 15 feet, 3 inches in diameter, lying 15 to 40 feet below the bottom of the river. Part way under the river sections of tube were placed under the westbound tunnel to permit the proposed third and fourth "Erie" tracks to diverge from the route to Exchange Place; the headings for these additional tunnels may still be seen between the existing tunnels just outside Hudson Terminal. At 10:17 on the morning of July 19, 1909, Miss Harriet Floyd McAdoo, daughter of the H&M president, mounted a platform in the mezzanine of Hudson Terminal before 2,000 invited guests, and upon receiving a signal from Chief Engineer Jacobs, pressed a button turning off every light in the station. A moment later, she touched another button, sending power into the third rails of the new line, relighting every light, and causing the crowd to break into cheers, which were instantly echoed outside by church bells and boat whistles. Fifty feet below the street, four special trains were waiting, and when these had filled, Mr. McAdoo gave the turn of the controller which sent the first train rolling under the Hudson to Jersey City, and ceremonies at Jersey City's City Hall, which were highlighted by the reading of a telegram of congratulations to Mr. McAdoo from President William Howard Taft. The Park Place station in Newark was new in 1912. It was closed when the H&M was rerouted into the PRR's new Newark station in 1937. The line initially ran on a three-minute headway as a shuttle to the Exchange Place Station, where passengers were whisked by elevator to the PRR Station and the street a hundred feet above the H&M platform level. Trains were reversed beyond the island platform station on a stub-end track known as the "Penn Pocket." The line instantly became popular because the running time was "Three minutes to New York," and was acclaimed by the press as saving over three million minutes a day for passengers, as the ride was 29 minutes shorter than the average ferry crossing. The tunnels between Hoboken, Erie Station, and Exchange Place were opened on August 2, 1909, and the tube junction allowing service between the Sixth Avenue Tunnel and the downtown tubes opened on September 20 of that year. The five-track Hudson Terminal was not only an engineering wonder; it was the most elaborate subway station in New York. It had a separate platform for baggage and for the removal of ashes from the boiler room beneath the station. The baggage service was introduced in 1910, but was a failure. Two baggage cars were built by J. G. Brill in the style of passenger equipment but with open sides. Baggage carts were rolled onto the cars with their cargo intact, transported to Hudson Terminal, and raised to the mezzanine via special elevators. For the passenger, the terminal had numerous concessions ranging from a meat market to a movie theatre. Mr. McAdoo initiated a system in which a wife could leave packages purchased in the city at the H&M baggage office for her husband to pick up later in the day. The H&M installed a large powder room in the terminal, and supplied the ladies with free powder and hairpins. For five cents any rest room patron was supplied with a towel and a bar of soap. The entrance to the 19th Street station on the uptown branch in 1908. It was closed in 1954. Illuminated train destination indicators were installed in the terminal. But Mr. McAdoo's chief pride was his ticket booths on wheels which could be pushed by a porter to any point in the terminal where they might be needed. Known as the "flying squadrons," each of the dozen movable booths was occupied by a pretty girl. When the terminal opened, the eager crowd at the Cortlandt Street entrance crushed against one of the "flying squadrons," sending it rolling across the terminal before police could rescue its panic-stricken inhabitant. Mr. McAdoo hired only women to sell tickets when he found that they were friendlier than men, and more efficient in handling change. However, whenever a gay blade tried to become better acquainted, a male "ticket chopper" would diplomatically urge him to move on. Although women at the time were fighting for their suffrage, Mr. McAdoo's outlook was such that he insisted upon paying them the same wages as men were paid. A New York women's organization suggested the idea of a special subway car for women riding H&M and IRT trains. Only Mr. McAdoo was willing to try it. A car equipped with a specially dressed guard was run on the tube trains for the ladies, but most woman wanted to ride with the men, so the "old maid's retreat", as the newspapers dubbed the idea, was dropped after a few months. The pleasant atmosphere of Hudson Terminal was increased by the lack of dispatcher's gangs. When a train's departure time arrived, the guards closed the doors and a bell rang in the motorman's cab, indicating that the train was ready to roll. The Pennsylvania, Lehigh Valley, Susquehanna, Lackawanna and Erie Railroads all rented space in the terminal for ticket offices. Railroad timetables listed the connecting departures from the Tube stations. Mr. McAdoo had ramps built in the Erie Station and Hudson Terminal in lieu of stairs, and in certain other stations elevators were installed to minimize the effort of reaching the platforms. In 1910 he experimented with automatic station indicators aboard three Tube cars, which would announce the next stop by illuminated signs. The experiment failed, so the signs were removed from the cars. A H&M Manhattan class "B" car built by Pressed Steel. These cars were placed into Jersey City-Hoboken-New York service in 1909. These and similar cars built until 1928 still provide all service on these lines but will be replaced soon. They seat 48 people and weigh 69,620 lbs. Above the terminal were built the Hudson Terminal Buildings, at the time the largest office complex in the world. Served by 39 elevators, the 275-foot, 22-story structures contained 24 thousand tons of steel, and had room for over 10,000 people in 4,000 offices on 27 acres of floor space. An exclusive restaurant club, founded by Mr. McAdoo, had its headquarters on the top floor of one of the buildings. Two additional tubes were started at Hudson Terminal to provide express service direct to the Erie Station. However, because of a lack of funds they were never completed. In another proposal, the Erie Railroad wanted a spur built from the existing tunnel near the H&M Station under Pavonia Avenue to a new station directly under the Erie Terminal. This plan was dropped and a long passageway was built to a large concourse under the Erie train platforms, with an entrance to every platform. Eighty cars were ordered by the H&M from the Pressed Steel Car Company to serve the Erie Station, but delivery was delayed because of a company strike. Because of the lack of rolling stock the Erie Station was not served by the H&M during the rush hours. Erie Station was the scene of another McAdoo experiment. In the concourse, a system of different combination of lights to distinguish the various Erie routes was tried. On August 2, 1909, the day of the initiation of Erie service, the first breakdown occurred on the H&M. A train stalled for a half hour under the river with both its air brake and power systems having been rendered inoperative because of a broken coupling. Mr. McAdoo, on this and later occasions, took newsmen to the scene of the trouble and offered them a full explanation of the delay-setting forth another policy which most other railroads never followed. Stairway from the Hudson Terminal Concourse to the platforms. PRR connections at Manhattan Transfer were posted. Mr. McAdoo, as a person, was very modest. He regarded himself as a "cog in the machinery." As a hero in the public eye, he was likened to Abraham Lincoln, because of his tall, gaunt build. He loved speed, commuting daily in a high-powered auto from his home in Yonkers, New York to his office. He became very prominent socially because of his easy-going, witty manner, and his ability to get along with people. Due to his constant thought to the comfort of his passengers, Mr. McAdoo won nationwide fame. The Greenfield, Massachusetts Courier compared the noisy, rough ride of the IRT to Borough Hall with the quiet, smooth H&M ride, and saluted Mr. McAdoo for his method of "pleasant" underground transportation. The H&M became known as the "McAdoo Tunnels," a term which finally became taboo in newspapers because of Mr. McAdoo's energetic protests. Mr. McAdoo wrote in his autobiography, "the millions that I was supposed to have made out of the Hudson Terminal enterprise are mythical millions. During the eleven years that I was president of the tunnels, I received... what amounted to an average of fifty thousand dollars a year." Complaints were virtually unheard of on the H&M. Mr. McAdoo noted in his autobiography that, although the line carried over 49 million passengers a year, less than 50 complaints were received. Those that were received Mr. McAdoo investigated himself. The H&M invited complaints and suggestions on how to improve service, and to insure the carrying out of the company's policy, "the public be pleased," Mr. McAdoo spent much of his time touring the system, going from train to train, keeping watch on the employees, talking with them, telling them that the passengers were the primary concern of the railroad. He said in a 1910 lecture at Harvard that "the condition of the railroad equipment and manners of the employees give a good picture of the management." In accord with his policy, cars and stations were cleaned daily. A H&M class "D" car built by Pressed Steel. These cars were placed into the Joint Service with the PRR between Hudson Terminal and Newark in 1911. They seated 52 passengers and weighed 73,000 lbs. They were replaced in 1958 by fifty "K"-class cars. The merits of the H&M service were advertised daily in the New York papers, as well as in German and Jewish-language newspapers. Timetables for the system were published, as well as brochures which listed all subway and steam railroad connections. Car advertisements were also displayed in the Interborough subway. In the effort to publicize the H&M, schedules printed in English and German were distributed on inboard ocean liners two days before their arrival in New York. A 1909 proposal to extend Tube service to Staten Island via the Central Railroad of New Jersey tracks was greeted with enthusiasm by the citizens of Bayonne and Staten Island. Tubes were to run from the Grove-Henderson Station to a station under the CNJ tracks at Communipaw where the CNJ would terminate its runs, eliminating the Jersey City Terminal and the CNJ ferry service. The tunnels would continue to a portal near the CNJ Van Nostrand Place Station, where H&M trains would run along the CNJ line, with stations at Greenville Avenue, 45th Street, 33rd Street, 22nd Street, and West 8th Street. South of West 8th Street, the trains would enter twin tubes under the Kill van Kull and run to points on Staten Island. This line was to be built after the Sixth Avenue-Grand Central Station extension, allowing uninterrupted travel from 42nd Street to Staten Island. PRR-H&M joint Manhattan Transfer station in 1912. Here Pennsy steam engines were replaced by electric DD-1's for Penn Station and passengers changed to H&M for downtown. On March 10, 1910 the Uptown Tunnel was extended to 33rd Street, with an intermediate station at 28th Street. The Uptown Terminal, built under the site of the Gimbels store, had baggage and ticket offices, and several railroads also opened ticket offices here. However, because of the proximity of Pennsylvania Station (only one block west), the H&M never carried baggage on the Uptown line. On September 6, 1910, the tube between Exchange Place and Grove-Henderson Streets was opened to traffic, and on November 10, the Henderson Street Yard was opened. At this time 130,000 people were using the Tubes daily. In September, 1910, the Public Service Commission advertised for bids for the proposed Triborough line-a subway to be independent of the IRT and the H&M. Not a bid was received to build the line with private capital, but Mr. McAdoo, who was in the hospital with appendicitis, offered to spend fifty million dollars of H&M funds for rolling stock and take a lease on the line for 25 years, if the City would build the line with its own money. He offered to put up a bond for one million dollars to insure his faith in the contract. The initial line, which was to run from Broadway to Union Square, to University Place, to Wooster Street, under Church Street to connect with Hudson Terminal, would more than pay for itself according to Mr. McAdoo. Map showing proposed extensions to the H&M system, 1909. The IRT management, which had allowed its cars and stations to decay, now realized that it could lose its monopoly on New York subway travel, offered to spend seventy-five million dollars to build additional subways, only to get Mr. McAdoo-a true competitor who was genuinely interested in providing good service-out of the way. In effect, Mr. McAdoo made the IRT improve its service by making his offer to operate the Triborough subway. The final chapter of the McAdoo-Hudson Tubes story began on April 16, 1906, when the H&M signed an agreement with the PRR to operate a joint service between Newark and Hudson Terminal. The earnings from this operation were to be split between the two companies, and the trains were to be operated by H&M crews who were required to pass a PRR rules test. The Hudson Tubes were extended for a half-mile beyond the Grove-Henderson Station, where they merged with the PRR right-of-way to Manhattan Transfer, a station in the Jersey Meadows which allowed passenger interchange with all PRR trains (and where PRR trains operating from Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan changed from DD-l type electric engines to steam locomotives or vice versa). Service began on October 1, 1911. The fare to Manhattan Transfer, which could be reached only by train, was 17 cents one-way, 30 cents round trip. Trains ran on a six-minute headway during the rush hours, and every 20 minutes during the base period. Service was provided every 30 minutes during the owl hours. On November 26, 1911 this service was extended via an elevated structure to a three-track stub-end Tube Terminal at Park Place in Newark, with an intermediate station in Harrison. The switch tower at Hudson Terminal in 1909. This tower has been modernized twice since and now has a color-coded US&S train describer. The 96 cars for this line were purchased jointly by the H&M and Pennsy from the Pressed Steel Car Company, and were similar in some respects to the H&M's other cars. The run between the two cities took less than 18 minutes at speeds which reached over 65 miles per hour at some points. The final station on the H&M system was opened at Summit Avenue (now Journal Square) in Jersey City on April 12, 1912 to allow a transfer between the Tubes and trolley lines of the Public Service Railway of New Jersey. The interior of an H&M car showing experimental station announcer in 1910. It was unsuccessful and removed shortly thereafter. > In 1913 Mr. McAdoo left his post as president of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad to become a member of President Woodrow Wilson's cabinet, where he served as Secretary of the Treasury. He had left a legacy which today is still saving thousands of commuters many minutes daily, but which more importantly is a monument to a man who possessed great determination and who strove, in spite of almost insurmountable problems, to mold his dream into reality. An editorial in the New York Globe truthfully summarized, "William G. McAdoo has taught the young men of today... that it is the mental and moral qualities of the man that are the most important forces after all, If there were more men like William G. McAdoo in the world, the rate of human progress would be considerably accelerated."

Certificate Vignette