Beautifully engraved Certificate from the famous owner of the Titanic International Mercantile Marine Company issued in the 1920's. This historic Stock Certificate was printed by the American Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with two vignettes. One of the vignettes is of a ship similar to the Titanic and the other is of a woman in a nautical setting. This item is hand signed by the company's officers and is over 93 years old.

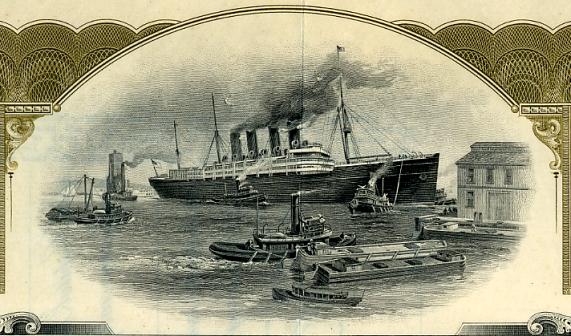

Certificate Vignette

The International Mercantile Marine shipping trust was formed in 1902 by J.P. Morgan. This company controlled the White Star Line which constructed three sister ships the Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic which are depicted in the unique, nautical vignette. Each of these ships was identical in size being 882 1/2 feet long and 92 1/2 feet wide. The Titanic sunk on its maiden voyage on April 15, 1912, after striking an iceberg at 11 20 p.m. on April 14,1912. The small cancellation holes on this preferred stock have the initials of JPM & Co which stands for the J.P Morgan Company.

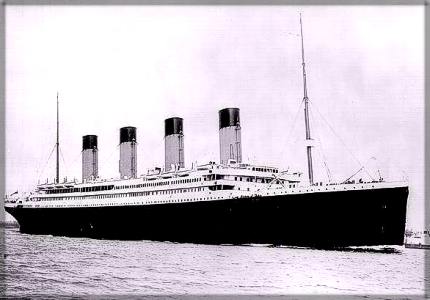

RMS Titanic Maiden Voyage

In 1898, Morgan Robertson (1861 - 1915), published his latest book. Robertson, the son of a sea captain, had joined the merchant marine service in 1877. By now he was a popular American writer of sea adventures. His latest book was about a gigantic ship wreck. The ship in the story was an 800 foot steel giant with three propellers, two masts, many water-tight compartments, and a top speed of more than 20 knots. She was the most luxurious and biggest ship in the world. Unfortunately, she had too few lifeboats. In the novel, the ship was struck by an iceberg on her starboard side at about midnight, sometime in April, and sank in the North Atlantic with a huge loss of life. Robertson named the book, Futility, and he called the ship, the Titan. On March 31, 1909, three months after work started on the first "Olympic-class" ocean liner Olympic, work was started on the second and most famous of the three. When J. Bruce Ismay, superintendent of the White Star Line, picked out her name, he had no idea how famous it would become. He named the ship, Titanic. For her brief life, Titanic was the largest moving object in the world. She was even more luxurious than her sister Olympic in that, she had two huge state rooms, each with it's own private promenade. She also had an enclosed forward promenade and a restaurant called the Cafe` Parisien. Although in 1913, Olympic had these features added to her, for the moment, Titanic was more luxurious. On May 31, 1911, Titanic was launched. She was put under the command of Captain Edward John Smith who was captain of Olympic for her first nine voyages before being transferred to this ship. The maiden voyage of Titanic was to be his last. After that, he was going to retire. The launch lasted only a minute. It took many tons of soap and oil to grease the runway that she slid down into the water. She wasn't christened because it was customary for the White Star Line to launch without a christening. The next ten months were spent installing machinery and fitting her interiors. On February 3, 1912 she was dry docked in the Thomson Graving Dock in Belfast, Northern Ireland where her propellers were put on and a final coat of paint was applied. At the beginning of March she, for a short while, joined her sister Olympic, who returned to dry dock for the replacement of a propeller blade on one of her three propellers. On April 2, 1912, Titanic set sail from Belfast on her sea trials. By the morning of April 10, 1912, she was sitting in Southampton, taking aboard her first passengers. Some of the passengers boarding here where supposed to go on other ships. But because of a coal strike, which meant that the people who dug up coal refused to work, there wasn't enough coal to power all the ships, so they were transferred to Titanic. It was almost noon when she left the White Star pier. Not many people know that disaster almost struck immediately. As she moved at six knots through the harbor, the huge suction made by the propellers caused the steamer New York, which was tied to the dock, to snap her lines and swing away from the dock to the port side. Tug boats frantically tried to get a line on the New York and Captain Smith cut the engines. The tug boat Vulcan was able to get New York out of the way without a collision. Although the incident ended happy, many passengers thought that this was a bad sign. Titanic moved on to Cherbourg, France where more people boarded. Since Cherbourg didn't have a deep enough port for Titanic, she had to anchor off the coast and wait for her next load of passengers to be ferried out to her onboard the ferries Nomadic and Traffic. These small ships where specially built for the Olympic-class ships, to replace the older ferry, Gallic, which was too small for ships the size of Titanic and Olympic. It was unknown to the passengers that many decks below, there was a coal fire in Boiler Room 5. Nine or ten men were assigned to hose down the fire and empty the coal bunker that was on fire. The ship then moved on to Queenstown, Ireland to pick up her last passengers. Again, she had to anchor off the coast while this time, the ferries Ireland and America brought her the passengers and mail. After the last people boarded, she set sail from Ireland carrying about 2220 people. Her 1335 passengers included many rich and famous. There was Scotland's Countess of Rothes. Mr. John Thayer, vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and his family. The richest man in America, Mr. John Jacob Astor and his significantly younger and pregnant second wife of seven months, Madeleine. There was mining millionaire Benjamin Guggenheim, British royals Sir Cosmo and Lady Lucile Duff Gordon, and the famous Denver millionairess, Molly Brown, who by the end of this voyage would have the title, "The Unsinkable Molly Brown". Over the next three days, it was a regular voyage. Thomas Andrews, the nephew of Lord Pirrie and managing director of Harland & Wolff, the company that built Titanic and her sisters, strolled the ship. Like Ismay on the maiden voyage of Olympic, he walked around, noting any flaws. During the voyage, millionaire George Widner of Philadelphia had a dinner party in the luxurious A la Carte Restaurant on C-deck. The gymnasium and racquet instructors encouraged people to use the gym equipment and racquet courts. The band played for the passengers at dinner, people used the pool and Turkish baths, third class passengers danced in the general room and in the well decks while the barber sold souvenirs to passengers. Stewards and stewardesses of all classes also played cards in the dinning saloons after their passengers had gone to bed. From Friday to Sunday, Titanic's wireless operators, John "Jack" Phillips and HaroldBride, received a large amount of ice warnings. The first few were sent to the captain at once. But as time went on, more and more passenger messages came into the wireless room and soon, there were so many, that they didn't have time to sent ice warnings to the bridge. Capt. Smith had told them that sending the passenger messages was very important; they were, after all, from paying customers. So, if Phillips and Bride wanted to get paid, they had to put passenger messages above everything else. On the night of Sunday, April 14, 1912 at about 11:40 PM, the unthinkable happened. Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee, two of the ship's look-outs, spotted an iceberg. First Officer Murdoch ordered the ship to be put hard to starboard. By turning the wheel to starboard, the ship would turn to port. He also ordered the engines to be put in full reverse. The iceberg kept getting closer and closer. Slowly, the ship began to turn. However, the turn came too late, Titanic was hit! The impact was so subtle, most people slept right through it. Second class chief steward John Hardy, who was awake at the time, later described it as, "A slight jar, a gradual jar; I did not think it was anything at all." Frederick Fleet said it was, "Just a slight grinding noise." To first class passenger George Harder, it was, "a sort of rumbling, scraping noise." Second class passenger Lawrence Beesley later wrote, "There came what seemed to me, nothing more than an extra heave of the engines, nothing more than that." In the backs of their heels, awake passengers and crew felt a slight vibration, nothing more. However, six small slits were cut into the ship's starboard side. In all, twelve square feet of the ship was left open to the sea. How could this be? Nineteen-twelve steel was weaker than steel today, but it should be able to hold up against a berg, right? Wrong. The cold waters of the Atlantic made her steel very brittle. Water began flowing in quickly. Thomas Andrews went down to G-deck to examine the damage. What he saw was devastating. The berg had damaged the first six of Titanic's water-tight compartments. She could stay afloat with her first four compartments damaged, but not six. At the same time, Captain Smith ordered Titanic's wireless operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride to send out distress messages. "What are you sending?" Bride asked a few minutes later. "CQD," replied Phillips. CQD was the standard call for distress at that time. "Send SOS," Bride suggested. "It's the new call and it may be your last chance to send it." The men chuckled, then went on with there work. It was 12:45 am, about an hour after Titanic had hit the iceberg, that the first life boat, No. 7, was lowered. The ship would have had 48 life boats to carry all passengers and crew. But, the line thought it would take up too much deck space for first and second class passengers. So, they only had fourteen standard boats that could hold sixty-five people, two emergency boats that could hold forty (emergency boats were just mini regular boats), and four collapsible life boats that could hold fifty-nine to sixty people (collapsible boats had a wooden bottom but their sides were canvas. You could fold them down to store the boat better.). The ship had a total of twenty boats, more than the required sixteen, but still not enough. As if having too few boats was enough, No. 7, a standard boat, was launched with only twenty-eight people in it. The next boat, No. 5, left only half full. In fact, most of the first boats to leave left this way. Emergency lifeboat No. 1 left the ship holding only twelve! This went on because the officers loading the boats didn't know that the boats had been tested and were capable of holding a lot of people. They were afraid that the boats would crack. However, after Thomas Andrews came out on deck and informed them about the boats, they began launching them with more people in them, although only one or two boats left the ship completely filled. It was around this time that Fourth Officer Boxhall fired the first distress rockets. In the beginning, not many passengers believed that the ship was really in danger so they didn't want to go in the boats. Most were confidant that the ship's safety features would keep her afloat. Even if the ship did founder, they were sure she would stay up long enough for help to arrive. Marjorie Newell-Robb was traveling with her father Arthur Newell and sister Madeline. After putting Marjorie and her sister in life boat No. 6, he said to them, "It seems more dangerous for you to get into that boat, than to stay here with me." However, Arthur died, and Marjorie and Madeline lived. Although on the upper part of the ship, everything seamed fine, down in the third class and crew area's of decks G and F, water was flooding in at a very fast rate. Somewhere between ten and twenty miles away was the Leyland Liner, Californian. This ship had stopped for the night due to ice. The ship's officers reported that they did see some strange ship in the night firing rockets in the night, but the officers on the ship had always been told, if you don't understand the signal, it's best to stay away. The Californian had also turned of it's wireless and didn't hear Titanic's calls. The officers tried to contact Titanic using a lamp, but when they got no reply, the disregarded it as just a passing liner. The next closest shipwas the Mount Temple, about forty to fifty miles away. Unfortunately, a treacherous ice field lay between her and the sinking ship. There was no hope of her getting through in time. The next closest ship to Titanic was the Cunard Liner, Carpathia, fifty-eight miles away! Jack Phillips had reached this ship on the wireless. Right after getting the distress signal, Carpathia's wireless operator, Harold Cottam, informed his captain, Arthur Rostron. Rostron immediately altered the ship's course. They began racing towards the sinking ship their full speed of fifteen knots. At the same time down in third class, there was complete chaos. Not many of the steerage passengers spoke English, so very few of them knew what was going on. Third class was seperated from second class and first class by locked gates. Unfortunatly, to some crew members, it was more important to save first and second class passengers than it was to save third class passengers. Daniel Buckley of third class later described being kept below. "They tried to keep us down on our steerage deck. They didn't want us to go up to the first class place at all. There was one steerage passenger, and just as he was going through a little gate, a fellow came along and shoved him back down into the steerage place." Buckley and a few others then bashed the gate and forced there way up to the boat deck where they got into boat No. 13. Most were dragged out of the boat by officers but an unknown woman wrapped her shawl around Buckley. The officers let him stay in the boat because they though he was a woman. As time went on, Titanic sank lower and lower into the water. By 1:45 A.M., water had flooded all the way up to B-deck. By now, it was un-deniable that the ship was in trouble. It was at about this time that boats 2 and 4 began to row away from the ship. With all the standard and emergency boats gone, crew members were now working to load collapsible life boats C and D. Second class passenger Winnie Troutt had made no attempt to save herself the entire night. She didn't think that a single woman like herself should be saved while husbands and wives were being separated. Suddenly, a man holding a baby came up to her. Although he didn't want to be saved, there was no one to save the baby. With no one else willing, Winnie said that she would save the child. She now had a good reason to be rescued. She then made her way to collapsible D and a crew member helped her and the baby into the boat. Once the boat was loaded , Chief Officer Wilde ordered it to be lowered. As it slowly descended to the water, passengers Hugh Woolner and Mauritz Björnström-Steffansson, who had helped load and launch collapsible C, saw that although the boat was mostly full, there was a small space in the bow of the life boat. The two men leaped over the side of the ship. Steffanson landed in it the life boat, but Woolner found himself hanging over the side and Steffanson pulled him in. By now, the water was just beginning to wet the forward part of the boat deck. There were now only two collapsible life boats left and over 1550 people still on the ship. In an article that appeared in the April 28, 1912 edition of The New York Times, Harold Bride described what happened next in the wireless room. "I looked out. The boat deck was awash. [Jack] Phillips clung on sending and sending. He clung on for about ten minutes, or maybe fifteen minutes, after the captain had released him. The water was then coming into our cabin. While he worked, something happened I hate to tell about. I was back in our room getting Phillips' money for him, and as I looked out the door, I saw a stoker, or somebody from below decks, leaning over Phillips from behind. He was too busy to notice what the man was doing. The man was slipping the lifebelt off Phillips' back! He was a big man, too. I am very small. I don't know what it was I got hold of. I remembered in a flash the way Phillips had clung on - how I had to fix his lifebelt because he was too busy to do it. I knew that man from below decks had his own lifebelt and should have known where to get it. I suddenly felt a passion not to let that man die a decent sailor's death. I wished he might have stretched rope or walked the plank. I did my duty. I hope I finished him. I don't know. We left him on the cabin floor of the wireless room, and he was not moving." After this event, Bride and Phillips left the wireless room. Phillips ran up aft and that was the last time Bride ever saw him alive. Bride then went to work on freeing collapsibles A and B. The two boats were stored on the roof of the officers' quarters. For collapsible A, crew men leaned several oars against the roof and the boat successfully slid down to the boat deck. Despite Sixth Officer Moody's idea that they should slide the boat into the water and let it be carried up, the crew members began to hook it up to the davits. Crew men attempted to do the same thing with collapsible B as had been done with A, but instead, B landed up-side-down. Before they had time to turn it over, the rising waters lifted up the boat. It was washed clear of the ship by the wave produced when the forward funnel collapsed and it drifted away with a few men clinging to it's bottom. More people would climb on as the boat drifted away from the ship. One of them was Second Officer Lightoller who had taken charge of the situation that night. In the air pocket under the overturned boat was Harold Bride. On top of the boat was his co- worker and friend Jack Phillips. At the same time on the starboard side of the ship, many of the people in collapsible A, who were just ready to shove off, were washed out by the wave of the rising water. The boat eventually drifted away, less that half full and very low in the water. Many of that boat's occupants suffered from frost bitten feet because of the freezing water in the bottom of the boat. At the same time on the Carpathia, there was lots of confusion. The passengers didn't know that Carpathia was preparing to save the passengers and crew of the sinking Titanic. They wondered, why were the crew members getting blankets and cots ready? Why were the cooks making large amounts of food and setting up tables in the dining rooms; breakfast wouldn't be served for many hours. Capt. Rostron had ordered the crew to ready the life boats so that they could be used to ferry passengers and crew to Carpathia if by chance, she managed to get to Titanic before the ship foundered. However, when passengers saw the boats uncovered, they began to worry that Carpathia was in danger. There was even a rumor going around that Carpathia had struck an iceberg and was sinking. Fourtunatly, this wasn't the case. Although she was steaming towards Titanic at her top speed, the tiny Cunard Liner was still many miles away from the sinking liner. By now on Titanic, all the boats were gone and more than 1520 people were left behind! At about 2:20, the stern rose high in the air. The lights, which had been bright the entire night, flickered, then went off. Suddenly, the ship violently cracked in two! The bow went down, and the stern quickly began to flood. After a few moments, the stern rose completely vertical. It bobbed up there for a minute or two, then foundered. Chief baker Charles Joughin, who was on the very stern as it went down, described it as riding an elevator. Joughin had drunk a lot of alcohol that night so he was well insulated against the twenty-eight degree water. He soon located collapsible B, which was only a few hundred meters away, and began paddling towards it. Eventually, he got on. "She's gone lads!" a man in boat No. 3 yelled. It was true. The great ocean liner was now lost. All she left behind was twenty lifeboats, many bodies, and hundreds of deck chairs floating in the water. In boat No. 1, the boat with only twelve people in it, leading fireman Charles Hendrickson, proposed the idea of going back to pick up swimmers, but was overruled. In boat No. 8, the Countess of Rothes and three others, also suggested the idea, but the same thing happened. The same went for most of the lifeboats. Boat No. 4, did go back and picked up seven swimmers, all of them crew members. They were Steward Andrew Cunningham, Assistant Storekeeper Frank Prentice, Steward Sidney Siebert (who died within a few hours), Able Bodied Seaman William Lyons (who also died within a few hours), Trimmer Thomas Dillon, Greaser Alfred White, and Lamp Trimmer Samuel Hemming. For people in the boats, things were hard. They had no food, no compasses, and very few blankets. Also, there weren't enough seamen in all of the boats to operate them. So, people like high-class men and women who had never before lifted a finger in labor now found themselves rowing oars and doing other things like that.. In life boat No. 6, Molly Brown took over. Despite the objections of Quartermaster Hichens, the man put in charge, Mrs. Brown had the women in the boat take turns rowing to keep warm and had people rotate on the job of manning the rudder. She gave her jacket to one person to keep him warm and had the people in the life boat sing too. Atop collapsible B, thirty men, including Colonel Archiblad Gracie, who would later write a detailed account of the disaster, began to recite the Lord's Prayer. On this boat Officer Lightoller had them all stand and sit in certain places to keep the boat balenced. The frozen occupant's of the swamped collapsible A, who were shin deep in water, also said the Lord's Prayer as they tried to keep warm. Three of this boat's passengers would not make it through the night. Fifth Officer Lowe in boat No. 14, had round up boats 10, 12, 4, and collapsible D. He ordered the five boats to be tied together. Lowe then evenly distributed the passengers and crew among four of the boats, and then, with a few other seamen, began to row No. 14 back to the scene. Sadly, they only found four living. they were third class passenger F. Lang, Steward Jack Stewart, first class passenger William Hoyt (who died within a few hours), and later, Bath Attendant Harold Phillimore. As time went on, there was nothing to do but wait. Finally, at about 4:00 AM, Carpathia was seen on the horizon. In boat No. 15, men used pieces of cloth as torches, in hopes to signal the liner. In emergency life boat No. 2, Fourth Officer Boxhall used green flares to do the same thing. People in all the lifeboats began lighting hats and pieces of paper on fire to use for signaling. Those without a torch or flash light, screamed at the top of their lungs to get the ship's attention. On collapsible B, Second Officer Lightoller began blowing his whistle. One by one, the boats came a long side Carpathia to be picked up. Since two, including Jack Phillips, had froze to death in the night, the now twenty- eight men clinging to collapsible B, leaped from that boat, to boats 4 and 12. They included Harold Bride, Officer Lightoller, and Colonel Gracie. Other boats were emptied, then cast adrift or taken onto the ship. After an unsuccessful search for survivors in the water, Carpathia set sail for New York City with her crew, 750 passengers, over 700 survivors, and thirteen of Titanic's lifeboats, plus her own boats. Of the 2220 people onboard Titanic, only 705 were saved. Among them was J. Bruce Ismay who had filled an empty space in collapsible C as it was being lowered. Although if he hadn't taken the seat it would have just gone empty, the papers criticized him for saving himself while others died. In first class, a total of 199 people were saved and 130 were lost. In second class, 119 were saved and 166 died. In third class, 174 were saved and 536 died. In the crew, 214 people were saved and 685 were lost. Of the eight officers, Captain E.J. Smith, Chief Officer Henry Wilde, First Officer William Murdoch, and Sixth Officer James Moody, perished. Only Second Officer Charles Lightoller, Third Officer Herbert Pitman, Forth Officer Joseph Boxhall, and Fifth Officer Harold Lowe survived. Thomas Andrews also perished. He was last seen in a state of shock in the 1st class smoking room, as the ship he built sank beneath him. None of the eight band members, who had nobly played to the very end to stop panic, survived. Of the twenty boats, only No. 14 and No. 4, had returned to save people after the ship had gone down. In 1985, Robert Ballard, with two others, Ralph Hollis and Martin Bowen, peered through the icy waters, more that two miles down on the ocean floor. They found Titanic's wreck using a small sub named Alvin. It was the first time Titanic had seen light in over 70 years. Since then, many expeditions have been made and many artifacts have been surfaced. At the American and British inquires into the loss of Titanic shortly after the disaster, many questions arouse. Why had the captain sailed through an ice field at 23 knots (the ship's top speed)? Why didn't the Californian take action when she saw the flares in the night? Was there another ship in between the Californian and the Titanic? Many people thought that the watertight doors should have been left open to cause even flooding. Although a test done on that theory over eighty years later proves that if the doors had been left open, the ship would have rolled onto it's side and sunk a full thirty minutes earlier that the real Titanic did, they didn't know that back then. We also know now that if the ship had rammed straight into the iceberg, only the first compartment would have been damaged and the ship wouldn't have foundered. But for the most part, the captain and officers did what they thought was best. I really don't think we should place the blame of the sinking on anyone. How can we? No one wanted Titanic to go down and no one meant for it to happen. The day after the sinking, the Prinz Albert of the Hamburg-Amerika Line reported passing a large iceberg. On one side, red paint "which had the appearance of having been made by the scraping of a vessel on the berg", a watcher said, was plainly visible. The ship's passengers and crew watched as the iceberg sailed on.