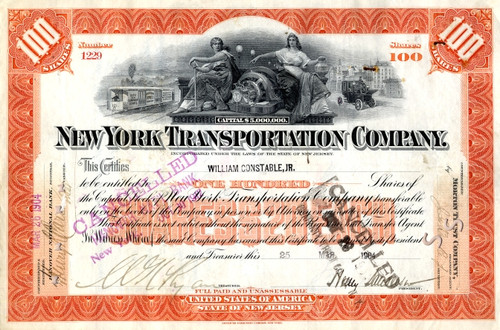

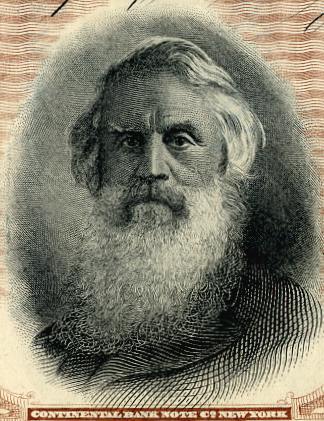

Beautifully engraved signed and unissued certificate from the American Cable Company dated in 1877. This historic document was printed by the Continental Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with vignette of an allegorical woman on clouds holding electricity and a engraving of Samuel F. B. Morse, inventor of the telegraph, at the bottom center of the certificate. This item is hand signed by the company's president and secretary and is over 136 years old. This certificate is made out to S.B. Morse and handsigned by David Chambers. Certificates we have seen from this company have water stains on top, which is consistent with this certificate.

Certificate Vignette

Certificate Vignette The American Cable Company owned a transatlantic cable between Sennen Cove (Penzance) in England, and Dover Bay, Canso (Nova Scotia).

Samuel Morse and the Telegraph Chappe semaphore from Telemuseum Samuel F. B. Morse developed an early interest in electricity at Yale from the lectures of Jeremiah Day and Benjamin Silliman in 1807. Although he pursued a career as an artist, Morse loved to tinker with machines and scientific problems, developing a wide range of talents that would make him the "American Leonardo." During a trip to Europe in 1830, he observed the French semaphore system for sending messages, as Morse described, "by telegraphic despatch" faster than the slow mail in America. He believed that an electric spark could send messages faster than the French semaphores ( see Telegraphs before Morse) During the return voyage to America on the ship Sully in October and November, 1832, Morse designed his telegraph using a simple code of dots and dashes. These would be recorded on paper tape by an electromagnetic lever moving a pencil up and down according to changes in the electric current sent from a distant transmitter. Morse apparently was unaware of earlier telegraphs based on the discoveries of Volta, Oersted and Ampere. His first device built in 1835 used a pencil and paper tape to record electric signals transmitted by a "portrule" metal bar device. The portrule was like the barrel organ; teeth represented digits that would be used to reconstruct words. The original code for the digit "1" was a single dot, represented on the portrule as a single tooth. The code for the digit "6" was a dot followed by a dash, represented on the portrule as a single tooth followed by an empty space. The teeth were loaded into the portrule like movable type. When the teeth touched a contact point, an electrical current went to the receiver where an electromagnet suspended from a canvas-stretcher frame moved a pencil, recording a wavy line on paper tape that corresponded to the teeth opening and breaking the circuit. Joseph Henry from Smithsonian The direct-current electricity came from gravity batteries that were the weak point in the 1835 model. With the help of Leonard Gale who had read Joseph Henry's 1831 article on electromagnetism, the original one-cell battery was replaced with a 20-cell battery, and 100 turns of wire were wound around the electromagnet. By Oct. 3, 1837, the device could transmit through 10 miles of wire, and Morse file a patent caveat. Gale owned a share of the patent, as well as a new partner, Arthur Vail, who helped redesign and improved the telegraph for a successful demonstration January 6, 1838, at Vail's Speedwell Iron Works in Morristown, New Jersey, transmitting 2 miles the sentence: "Railroad cars just arrived, 345 passengers." By the time of the next demonstration January 24 at New York University, Morse developed a new code with dots and dashes representing letters rather than digits. Vail's family later claimed that Arthur Vail invented the Morse code, but Vail himself denied it and wrote that Morse invented the code. Vail's most important contribution was to replace the portrule with a hand-operated key that reproduced the code by means of a pattern of clicks. On Feb. 21, 1838, Morse demonstrated his telegraph to President Van Buren and the Cabinet in Washington. To help sell his telegraph to the government, Morse accepted the partnership of Francis O.J. "Fog" Smith, Chairman of the Committee on Commerce. However, Congress would not pass the bill to spend $30,000 for a telegraph line until March 3, 1843. Ezra Cornell was hired to lay the underground pipe for the wires from Washington to Baltimore using a trenching plow of his own design. When the pipe was found to be defective, Morse put the wires on overhead poles as Dyar had done in Long Island and Wheatstone in England. The double wires were insulated with gum shellac and raised on the chestnut poles 24 feet high and 200 feet apart, starting north from Washington in March, 1844, reaching Annapolis Junction by the time the Whig convention met May 1 in Baltimore. When Clay and Freylinheusen won the nomination, the news was telegraphed by Vail in Annapolis Junction to Morse at the Capitol in Washington. On May 24 the line was finished and Morse sent to Baltimore the code for "What hath God wrought!" (chosen by Annie Ellsworth from Numbers 23:23). Telegraph operators quickly learned to send and receive solely from the sound of the clicks rather than use paper tape. Morse was not the first to invent a telegraph, but he is known as the "father" of the telegraph because he created a new industry. Hiram Sibley and Ezra Cornell made Western Union into one of the most influential corporate empires in American history. The electric telegraph was the stimulus for inventors to search for better methods of sending and recording all kinds of messages, including voice and music. David E. Hughes, a Professor of Music at St. Joseph's College in Kentucky, invented in 1855 a keyboard telegraph with rotating type-wheel printer that became the foundation of the modern telex industry. In Germany, telegraph printers were patented as early as 1848 and Philip Reis invented an acoustic transmitter in 1861 that used a diaphragm to open and close an electrical circuit. He called it a "telephone" hoping to use it to reproduce speech and music but was unsuccessful. Elisha Gray and his Western Electric Company in Chicago had also invented an improved telegraph receiver, calling it a "telephone" after 1874 because it produced a wide range of sounds, but failed make a similar transmitter.

Certificate Vignette

Certificate Vignette

Samuel Morse and the Telegraph Chappe semaphore from Telemuseum Samuel F. B. Morse developed an early interest in electricity at Yale from the lectures of Jeremiah Day and Benjamin Silliman in 1807. Although he pursued a career as an artist, Morse loved to tinker with machines and scientific problems, developing a wide range of talents that would make him the "American Leonardo." During a trip to Europe in 1830, he observed the French semaphore system for sending messages, as Morse described, "by telegraphic despatch" faster than the slow mail in America. He believed that an electric spark could send messages faster than the French semaphores ( see Telegraphs before Morse) During the return voyage to America on the ship Sully in October and November, 1832, Morse designed his telegraph using a simple code of dots and dashes. These would be recorded on paper tape by an electromagnetic lever moving a pencil up and down according to changes in the electric current sent from a distant transmitter. Morse apparently was unaware of earlier telegraphs based on the discoveries of Volta, Oersted and Ampere. His first device built in 1835 used a pencil and paper tape to record electric signals transmitted by a "portrule" metal bar device. The portrule was like the barrel organ; teeth represented digits that would be used to reconstruct words. The original code for the digit "1" was a single dot, represented on the portrule as a single tooth. The code for the digit "6" was a dot followed by a dash, represented on the portrule as a single tooth followed by an empty space. The teeth were loaded into the portrule like movable type. When the teeth touched a contact point, an electrical current went to the receiver where an electromagnet suspended from a canvas-stretcher frame moved a pencil, recording a wavy line on paper tape that corresponded to the teeth opening and breaking the circuit. Joseph Henry from Smithsonian The direct-current electricity came from gravity batteries that were the weak point in the 1835 model. With the help of Leonard Gale who had read Joseph Henry's 1831 article on electromagnetism, the original one-cell battery was replaced with a 20-cell battery, and 100 turns of wire were wound around the electromagnet. By Oct. 3, 1837, the device could transmit through 10 miles of wire, and Morse file a patent caveat. Gale owned a share of the patent, as well as a new partner, Arthur Vail, who helped redesign and improved the telegraph for a successful demonstration January 6, 1838, at Vail's Speedwell Iron Works in Morristown, New Jersey, transmitting 2 miles the sentence: "Railroad cars just arrived, 345 passengers." By the time of the next demonstration January 24 at New York University, Morse developed a new code with dots and dashes representing letters rather than digits. Vail's family later claimed that Arthur Vail invented the Morse code, but Vail himself denied it and wrote that Morse invented the code. Vail's most important contribution was to replace the portrule with a hand-operated key that reproduced the code by means of a pattern of clicks. On Feb. 21, 1838, Morse demonstrated his telegraph to President Van Buren and the Cabinet in Washington. To help sell his telegraph to the government, Morse accepted the partnership of Francis O.J. "Fog" Smith, Chairman of the Committee on Commerce. However, Congress would not pass the bill to spend $30,000 for a telegraph line until March 3, 1843. Ezra Cornell was hired to lay the underground pipe for the wires from Washington to Baltimore using a trenching plow of his own design. When the pipe was found to be defective, Morse put the wires on overhead poles as Dyar had done in Long Island and Wheatstone in England. The double wires were insulated with gum shellac and raised on the chestnut poles 24 feet high and 200 feet apart, starting north from Washington in March, 1844, reaching Annapolis Junction by the time the Whig convention met May 1 in Baltimore. When Clay and Freylinheusen won the nomination, the news was telegraphed by Vail in Annapolis Junction to Morse at the Capitol in Washington. On May 24 the line was finished and Morse sent to Baltimore the code for "What hath God wrought!" (chosen by Annie Ellsworth from Numbers 23:23). Telegraph operators quickly learned to send and receive solely from the sound of the clicks rather than use paper tape. Morse was not the first to invent a telegraph, but he is known as the "father" of the telegraph because he created a new industry. Hiram Sibley and Ezra Cornell made Western Union into one of the most influential corporate empires in American history. The electric telegraph was the stimulus for inventors to search for better methods of sending and recording all kinds of messages, including voice and music. David E. Hughes, a Professor of Music at St. Joseph's College in Kentucky, invented in 1855 a keyboard telegraph with rotating type-wheel printer that became the foundation of the modern telex industry. In Germany, telegraph printers were patented as early as 1848 and Philip Reis invented an acoustic transmitter in 1861 that used a diaphragm to open and close an electrical circuit. He called it a "telephone" hoping to use it to reproduce speech and music but was unsuccessful. Elisha Gray and his Western Electric Company in Chicago had also invented an improved telegraph receiver, calling it a "telephone" after 1874 because it produced a wide range of sounds, but failed make a similar transmitter.