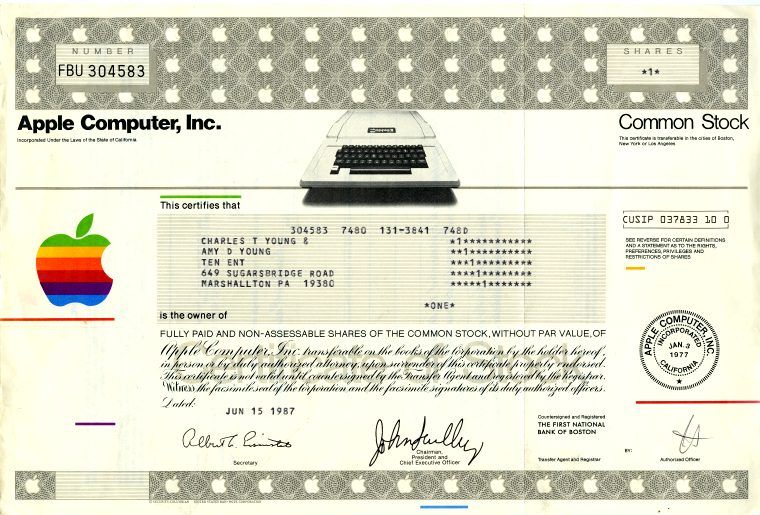

Beautiful certificate from the Apple Computer issued in 1985. This historic document was printed by Security-Columbian Bank Note Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of an Apple II computer and the apple logo. This item has the signatures of the Company's Chairman and President, John Scully and Secretary and is over 37 years old. Light folds.

Certificate Vignette

Certificate Vignette

Certificate

Apple Computer, Inc. engages in the design, manufacture, and marketing of personal computers and related software, services, peripherals, and networking solutions worldwide. It also designs, develops, and markets a line of portable digital music players along with related accessories and services, including the online distribution of third-party music and audio books. The company's products and services include the Macintosh line of desktop and notebook computers; the Power Mac line of desktop personal computers; the iPod digital music player; the Xserve server; Xserve RAID storage products, a portfolio of consumer and professional software applications; the Mac OS X operating system; the online iTunes Music Store, a portfolio of peripherals that support the Macintosh and iPod product lines; PowerSchool software product, a Web-based student information system for K-12 schools and school districts; and a variety of other service and support offerings. It also offers various associated Apple-branded computer hardware peripherals, including iSight digital video cameras, and a range of flat panel TFT active-matrix digital color displays. In addition, the company sells a variety of third-party products, including computer printers and printing supplies, storage devices, computer memory, digital video and still cameras, personal digital assistants, iPod accessories, and various other computing products and supplies. The company offers its products to education, consumer, creative professional, business, and government customers. Apple Computer sells its products through its online stores, retail stores, direct sales force, as well as through third-party wholesalers, resellers, and value added resellers. The company operated 110 retail open stores, as of June 30, 2005. Apple Computer was founded in 1976 by Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs. Apple Computer is headquartered in Cupertino, California Apple ignited the personal computer revolution in the 1970s with the Apple II and reinvented the personal computer in the 1980s with the Macintosh. Apple is committed to bringing the best personal computing experience to students, educators, creative professionals and consumers around the world through its innovative hardware, software and Internet offerings.

John Sculley (born April 6, 1939) was a vice-president (1970-1977) and president of PepsiCo (1977-1983), until he became CEO of Apple on April 8, 1983, a position he held until leaving in 1993. Sculley is currently a partner in Sculley Brothers, a private investment firm formed in 1995. He is best known for his marketing skills, particularly in his introduction of 'the Pepsi Challenge' at PepsiCo, which allowed the company to gain market share from its primary rival, Coca Cola. Sculley used similar marketing strategies at Apple throughout the 1980s and 1990s to mass market Macintosh personal computers. In May 1987, Sculley was named Silicon Valley's top-paid executive, with an annual salary of US$2.2M. Background and personal life Sculley was born in the United States, but within a week of his birth, he and his family were relocated to Bermuda, and subsequently to Brazil and Europe.[2] Sculley attended high school at St. Mark's School in Southborough, MA. He ultimately received a bachelor's degree in architectural design from Brown University and an MBA from the Wharton School of Business. Sculley has two brothers, Arthur and David Sculley, with whom he formed a private investment firm, Sculley Brothers LLC, in 1995. 196782: Sculley at Pepsi-Cola Sculley joined the Pepsi-Cola division of PepsiCo in 1967 as a trainee, where he participated in a six-month training program at a bottling plant in Pittsburgh. [4] In 1970, at the age of 30, Sculley became the company's youngest marketing vice-president. As vice-president of marketing at Pepsi, Sculley initiated one of the company's first consumer-research studies, an extended in-home product test in which 350 families participated. As a result of the research, Pepsi decided to launch new, larger and more varied packages of their soft drinks. [5] In 1970, Pepsi set out to dethrone Coca Cola as the market leader of the industry, in what would eventually become known as the Cola Wars. Pepsi began spending more on marketing and advertising, typically paying between US$200,000 and $300,000 for each television spot, while most companies spent between $15,000 and $75,000. With the Pepsi Generation campaign, Pepsi aimed to overturn Coca Cola's classic marketing. At Pepsi, Sculley also took the position of managing PepsiCo's International Food Operations division, shortly after he visited a failing potato-chip factory in Paris. PepsiCo's Food division was their only money-losing division, with revenues of US$83 million and losses of $16 million. To make the food division profitable, Sculley hired new managers from Frito-Lay and improved product quality, as well as improving accounts and establishing financial controls. Within three years, the food division was making US$300 million in revenues and $40 million in profit. Sculley is best known at Pepsi for the Pepsi Challenge, an advertising campaign he started in 1975 to compete against Coca Cola to gain market share, using heavily-advertised taste tests. It claimed based on Sculley's own research that Pepsi-Cola tasted better than Coca-Cola. The Pepsi Challenge included a series of television advertisements that first aired in the early 1970s, featuring lifelong Coca-Cola drinkers participating in blind taste tests. Pepsi's soft drink was always chosen as the preferred product by the participant; however, these tests have been criticized as being biased. The Pepsi Challenge was mostly targeted at the Texas market, because Pepsi had a significantly low market share there at the time. The campaign was successful, significantly increasing Pepsi's market share in that state. At the time the Pepsi Challenge was started, Sculley was senior vice-president of United States sales and marketing operations at Pepsi. In 1977, Sculley was named Pepsi's youngest-ever president. 198393: the Sculley era at Apple BusinessWeek's November 1984 magazine cover featuring Steve Jobs (left) and John Sculley (right).While chairman of Apple Computer, Steve Jobs recruited Sculley from Pepsi. Jobs is reputed to have asked Sculley: Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change the world? Apple chose Sculley because they wanted him to apply his marketing skills to the personal computer market, particularly to the Macintosh.[citation needed] During the brief "honeymoon" period, Jobs and Sculley appeared on stage together addressing employees, dressed in similarly--pressed khakis with cuffs, powder-blue button-down shirts, penny loafers or Top-Siders,--very Brooks Brothers, but casual: no tie, no suit. Jobs was visibly dressed up from his former jeans, beard, T-shirt, and vest, whereas Sculley was visibly dressed-down from the Pepsico days: he often wore plaid shirts, loden-green cords, and penny-loafers without socks: straight from The Official Preppy Handbook, which explains the ways insiders dress down.[citation needed] Sculley raised the initial price of the Macintosh to $2,495 from the originally planned $1,995, using the additional money for higher profit margins and expensive advertising campaigns. Eventually, the honeymoon ended. People joked that the difference between Apple computer and a Boy Scout troop is that the scouts have adult supervision. Well, Apple now did. After the Lisa shipped, and sold disastrously, and the Macintosh shipped, and sold extremely well, but yet did not put the IBM PC out of business, some of the privileges of the elite development groups were trimmed, and projects were subject to stricter review for usefulness, marketability, feasibility, and reasonable cost. A power struggle between Jobs and Sculley had become readily apparent. Jobs became "non-linear": he kept meetings running past midnight, sent out lengthy faxes, then called new meetings at 7 am. After one such meeting in 1985, the Board of Directors lost patience and stripped Jobs of all operational responsibilities, three months after Jobs' 30th birthday. Microsoft threatened to discontinue Microsoft Office for the Macintosh if Apple did not license parts of the Macintosh graphical user interface to use in the Windows operating system. Under pressure, Sculley agreed, a decision which later affected the Apple v. Microsoft lawsuit. Also while at Apple, Sculley coined the term personal digital assistant (PDA) referring to the Apple Newton, one of the world's first PDAs. In 1987, Sculley published his autobiography, Odyssey. As a benevolent gesture, he gave each Apple employee a copy at Apple's expense, in the hope of inspiring "excellence". Shortly afterwards, Jean-Louis Gassée, Vice President of Product Development, gave each employee in his division a copy of Fred Brooks's book The Mythical Man Month, in the hope of inspiring good sense in planning and carrying out engineering projects. The "Sculley Era" at Apple was characterized by market division and further subdivision, with a large number of models covering what critics called a too-finely subdivided range. Each production model was marketed under different names in each of several primary markets -- home, education, and business; with time, each of these models generated upgrades and variations, which created unforeseen incompatibilities: keeping the operating system (The Macintosh System Software) compatible with all Macintosh models was a never-ending task. This strategy backfired, as it resulted in high engineering, manufacturing, and marketing costs, as well as market confusion. Buyers would look at similar machines in a store, each conceived for a particular market but usable elsewhere, and with comparable performance specifications, and wonder: "Which one do I buy? The home machine? The business machine? The school machine? They all look the same (and none run MS-DOS or Windows)." Too many products with similar specifications led to decreased profits, despite high gross margins. Given his apparent inability to effectively manage Apple's product line, Apple's board ultimately forced Sculley out. He was replaced by Michael Spindler, after a brief power struggle between Spindler and Gassée, which led to Gassée's exit. Another side effect of Sculley's tenure was the destruction of Apple's engineering department. As the company grew, mid- and low-level managers within the company found it fairly easy to gain funding for practically any project. Apple became filled with these projects, many of which had little commercial potential. When money tightened in the early 1990s, this resulted in a sweeping round of empire building, in which mid-level managers attempted to take over as many projects as possible in order to make their projects more difficult to discontinue. Between 1990 and 1995, very few products were successful, with the exception of Mac OS updates, while massive projects such as QuickDraw GX and PowerTalk were released in essentially unusable forms. In the early 1990s, at enormous expense, Sculley led Apple to port its operating system to run on a new microprocessor, the PowerPC. Sculley later acknowledged this was his greatest mistake, indicating that he should instead have targeted the dominant Intel architecture. Although Sculley asserted Apple's most important goal was to crack the business PC market, during his ten years at the helm, Apple failed to address the key complaint of business buyers about the Macintosh operating system: poor system stability caused by a lack of memory protection and pre-emptive multitasking. In 1987, Sculley made several famous predictions in a Playboy interview. He predicted that the Soviet Union would land a man on Mars within the next 20 years and claimed that optical storage media such as the CD-ROM would revolutionize the use of personal computers. Some of his ideas for the Knowledge Navigator would eventually be fulfilled, not by Apple itself, but by the Internet and the World Wide Web during the 1990s. History from Wikipedia and OldCompanyResearch.com (old stock certificate research service).