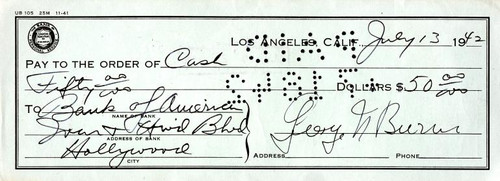

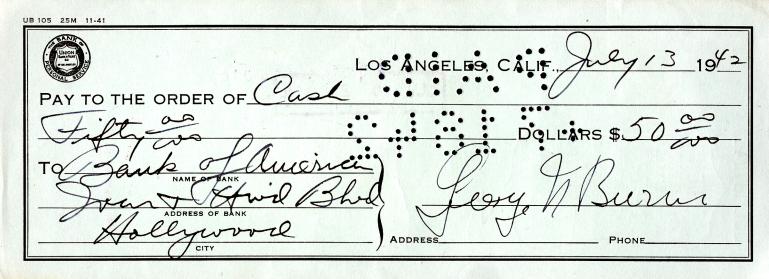

George Burns signed Check issued in 1942.

Check George Burns (January 20, 1896 March 9, 1996), born Naftaly (Nathan) Birnbaum, was an American comedian, actor, and writer. He was one of the few entertainers whose career successfully spanned vaudeville, film, radio, and television. His arched eyebrow and cigar smoke punctuation became familiar trademarks for over three quarters of a century. Beginning at the age of 79, Burns' career was resurrected as an amiable, beloved and unusually active old comedian, continuing to work until shortly before his death, in 1996, at the age of 100. Early life Naftaly (Nathan) Birnbaum was born on January 20, 1896 in New York City, the ninth of 12 children born to Louis "Lippe" and Dorah (née Bluth) Birnbaum, Jewish immigrants who had come to the United States from Romania. Burns was also an active member of the First Roumanian-American congregation.[3] His father was a substitute cantor at the local synagogue but usually worked as a coat presser. During the influenza epidemic of 1903, Lippe Birnbaum contracted the flu and died at the age of 47. Nattie (as he was then called) went to work to help support the family, shining shoes, running errands, and selling newspapers. When he landed a job as a syrup maker in a local candy shop at age seven, he was "discovered," as he recalled long after: We were all about the same age, six and seven, and when we were bored making syrup, we used to practice singing harmony in the basement. One day our letter carrier came down to the basement. His name was Lou Farley. Feingold was his real name, but he changed it to Farley. He wanted the whole world to sing harmony. He came down to the basement once to deliver a letter and heard the four of us kids singing harmony. He liked our style, so we sang a couple more songs for him. Then we looked up at the head of the stairs and saw three or four people listening to us and smiling. In fact, they threw down a couple of pennies. So I said to the kids I was working with, 'no more chocolate syrup. It's show business from now on'. We called ourselves the Pee-Wee Quartet. We started out singing on ferryboats, in saloons, in brothels, and on street corners. We'd put our hats down for donations. Sometimes the customers threw something in the hats. Sometimes they took something out of the hats. Sometimes they took the hats. -- George Burns Burns quit school in the fourth grade to go into show business full-time. Like many performers of his generation, he tried practically anything he could to entertain, including working with a trained seal, trick roller skating, teaching dance, singing, and adagio dancing in small-time vaudeville. During these years, he began smoking cigars and later in his older years was characteristically known as doing shows and puffing on his cigar.[5] He adopted the stage name by which he would be known for the rest of his life. He claimed in a few interviews that the idea of the name originated from the fact that two star major league players (George H. Burns and George J. Burns, unrelated) were playing major league baseball at the time. Both men achieved over 2000 major league hits and hold some major league records. Burns also was reported to have taken the name George from his brother Izzy (who hated his own name so he changed it to "George"), and the Burns from the Burns Brothers Coal Company (he used to steal coal from their truck). He normally partnered with a girl, sometimes in an adagio dance routine, sometimes comic patter. Though he had an apparent flair for comedy, he never quite clicked with any of his partners, until he met a young Irish Catholic lady in 1923. "And all of a sudden," he said famously in later years "the audience realized I had a talent. They were right. I did have a talent--and I was married to her for 38 years." His first wife was Hannah Siegel (stage name: Hermosa Jose), one of his dance partners. The marriage, never consummated, lasted 26 weeks and happened because her family would not let them go on tour unless they were married. They divorced at the end of the tour. George Burns, Gracie Allen and children aboard Matson flagship Lurline just before they sailed for Hawaii, 1938 Grace Ethel Cecile Rosalie Allen was born into an Irish Catholic show business family and educated at Star of the Sea Convent School in San Francisco, California in girlhood. She began in vaudeville around 1909, teamed as an Irish-dance act, "The Four Colleens", with her sisters, Bessie, Hazel, and Pearl. She met George Burns and the two immediately launched a new partnership, with Gracie playing the role of the "straight man" and George delivering the punchlines as the comedian. Burns knew something was wrong when the audience ignored his jokes but snickered at Gracie's questions. Burns cannily flipped the act around: After a Hoboken, New Jersey performance in which they tested the new style for the first time, Burns' hunch proved right. Gracie was the better "laugh-getter," especially with the "illogical logic" that formed her responses to Burns' prompting comments or questions. Allen's part was known in vaudeville as a "Dumb Dora" act, named after a very early film of the same name that featured a scatterbrained female protagonist, but her "illogical logic" style was several cuts above the Dumb Dora stereotype developed by American cartoonist Chic Young, as was Burns' understated straight man. The twosome worked the new style tirelessly on the road, building a following, as well as a reputation for being a reliable "disappointment act" (one that could fill in for another act on short notice). Burns and Allen were so consistently dependable that vaudeville bookers elevated them to the more secure "standard act" status, and finally to the vaudevillian's dream: the Palace Theatre in New York. Burns wrote their early scripts, but was rarely credited with being such a brilliant comedy writer. He continued to write the act through vaudeville, films, radio, and, finally, television, first by himself, then with his brother Willie and a team of writers. The entire concept of the Burns and Allen characters, however, was one created and developed by Burns. As the team toured in vaudeville, Burns found himself falling in love with Allen, who was engaged to another performer at the time, Benny Ryan. After several attempts to win her over, he finally succeeded (by accident) after making her cry at a Christmas party. She told a friend that "if George meant enough to her to make her cry she must be in love with him". They were married in Cleveland, Ohio on January 7, 1926, somewhat daring for those times, considering Burns' Jewish and Allen's Irish Catholic upbringing.[8] They adopted their daughter, Sandra, in 1934 and son, Ronnie, in 1935. (For her part, Allen also endeared herself to her in-laws by adopting her mother-in-law's favorite phrase, used whenever the older woman needed to bring her son back down to earth: "Nattie, you're such a schmuck," using a diminutive of his given name. When Burns' mother died, Allen comforted her grief-stricken husband with the same phrase.) In later years Burns admitted that, following an argument over a pricey silver table centerpiece Allen wanted, he had a very brief affair with a Las Vegas showgirl. Stricken by guilt, he phoned one of his best friends, Jack Benny, and told him about the indiscretion. However, Allen overheard the conversation and Burns quietly bought the expensive centerpiece and nothing more was said. Years later, he discovered that Allen had told one of her friends about the episode finishing with "You know, I really wish George would cheat on me again. I could use a new centerpiece." After fighting a long battle with heart disease, Gracie Allen suffered a fatal heart attack in her home on August 27, 1964 at the age of 69. She was entombed in a mausoleum at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery. In his second book, They Still Love Me in Altoona, Burns wrote that he found it impossible to sleep after her death until he decided to sleep in the bed she used during her illness. He also visited her grave once a month, professing to talk to her about whatever he was doing at the time -- including, he said, trying to decide whether he really should accept the Sunshine Boys role Jack Benny had to abandon because of his own failing health. He visited the tomb with Ed Bradley during a 60 Minutes interview on November 6, 1988. Stage to screen Burns and Allen got a start in motion pictures with a series of comic short films in the late 1930s. Their feature credits in the mid- to late-1930s included The Big Broadcast; International House (1933), Six of a Kind (1934), The Big Broadcast of 1936, The Big Broadcast of 1937, A Damsel in Distress (1937) in which they danced step for step with Fred Astaire, and College Swing (1938), in which Bob Hope made one of his early film appearances. Burns and Allen were indirectly responsible for the Bob Hope and Bing Crosby series of "Road" pictures. In 1938, William LeBaron, producer and managing director at Paramount, had a script prepared by Don Hartman and Frank Butler. It was to star Burns and Allen with Bing Crosby, who was then already an established star of radio, recordings and the movies. The story did not seem to fit the comedy team's style, so LeBaron ordered Hartman and Butler to rewrite the script to fit two male co-stars: Hope and Crosby. The script was titled Road to Singapore and it made motion picture history when it was released in 1940. Radio stars Burns and Allen first made it to radio as the comedy relief for bandleader Guy Lombardo, which did not always sit well with Lombardo's home audience. In his later memoir, The Third Time Around, Burns revealed a college fraternity's protest letter, complaining that they resented their weekly dance parties with their girl friends to "Thirty Minutes of the Sweetest Music This Side of Heaven" had to be broken into by the droll vaudeville team. In time, though, Burns and Allen found their own show and radio audience, first airing on February 15, 1932 and concentrating on their classic stage routines plus sketch comedy in which the Burns and Allen style was woven into different little scenes, not unlike the short films they made in Hollywood. They were also good for a clever publicity stunt, none more so than the hunt for Gracie's missing brother, a hunt that included Gracie turning up on other radio shows searching for him as well. The couple was portrayed at first as younger singles, with Allen the object of both Burns' and other cast members' affections. Most notably, bandleaders Ray Noble (known for his phrase, "Gracie, this is the first time we've ever been alone") and Artie Shaw played "love" interests to Gracie. In addition, singer Tony Martin played an unwilling love interest of Gracie's, in which Gracie "sexually harassed" him, by threatening to fire him if the romantic interest wasn't returned. In time, however, due to slipping ratings and the difficulty of being portrayed as singles in light of the audience's close familiarity with their real-life marriage, the show adapted in the fall of 1941 to present them as the married couple they actually were. For a time, Burns and Allen had a rather distinguished and popular musical director: Artie Shaw, who also appeared as a character in some of the show's sketches. A somewhat different Gracie also marked this era, as the Gracie character could often be found to be mean to George. George Your mother cut my face out of the picture. Gracie Oh, George, you're being sensitive. George I am not! Look at my face! What happened to it? Gracie I don't know. It looks like you fell on it. Or Census Taker What do you make? Gracie I make cookies and aprons and knit sweaters. Census Taker No, I mean what do you earn? Gracie George's salary. As this format grew stale over the years, Burns and his fellow writers redeveloped the show as a situation comedy in the fall of 1941. The reformat focused on the couple's married life and life among various friends, including Elvia Allman as "Tootsie Sagwell," a man-hungry spinster in love with Bill Goodwin, and neighbors, until the characters of Harry and Blanche Morton entered the picture to stay. Like The Jack Benny Program, the new George Burns & Gracie Allen Show portrayed George and Gracie as entertainers with their own weekly radio show. Goodwin remained, his character as "girl-crazy" as ever, and the music was now handled by Meredith Willson (later to be better known for composing the Broadway musical The Music Man). Willson also played himself on the show as a naive, friendly, girl-shy fellow. The new format's success made it one of the few classic radio comedies to completely re-invent itself and regain major fame. The supporting cast during this phase included Mel Blanc as the melancholy, ironically named "Happy Postman" (his catchphrase was "Remember, keep smiling!"); Bea Benaderet (later Cousin Pearl in The Beverly Hillbillies, Kate Bradley in Petticoat Junction and the voice of Betty Rubble in The Flintstones) and Hal March (later more famous as the host of The $64,000 Question) as neighbors Blanche and Harry Morton; and the various members of Gracie's ladies' club, the Beverly Hills Uplift Society. One running gag during this period, stretching into the television era, was Burns' questionable singing voice, as Gracie lovingly referred to her husband as "Sugar Throat." The show received and maintained a Top 10 rating for the rest of its radio life. In the fall of 1949, after twelve years at NBC, the couple took the show back to its original network CBS, where they had risen to fame from 1932 1937. Their good friend Jack Benny reached a negotiating impasse with NBC over the corporation he set up ("Amusement Enterprises") to package his show, the better to put more of his earnings on a capital-gains basis and avoid the 80 percent taxes slapped on very high earners in the World War II period. When CBS executive William S. Paley convinced Benny to move to CBS (Paley, among other things, impressed Benny with his attitude that the performers make the network, not the other way around as NBC chief David Sarnoff reputedly believed), Benny in turn convinced several NBC stars to join him, including Burns and Allen. Thus did CBS reap the benefits when Burns and Allen moved to television in 1950. George Burns and Gracie Allen, 1955. On television, The George Burns & Gracie Allen Show put faces to the radio characters audiences had come to love. A number of significant changes were seen in the show: A parade of actors portrayed Harry Morton: Hal March, The Life Of Riley alumnus John Brown, veteran movie and television character actor Fred Clark, and future Mister Ed co-star Larry Keating. Burns often broke the fourth wall, and chatted with the home audience, telling understated jokes and commenting wryly about what show characters were doing or undoing. In later shows, he would actually turn on a television and watch what the other characters were up to when he was off camera, then return to foil the plot. When announcer Bill Goodwin left after the first season, Burns hired veteran radio announcer Harry Von Zell to succeed him. Von Zell was cast as the good-natured, easily-confused Burns and Allen announcer and buddy. He also became one of the show's running gags, when his involvement in Gracie's harebrained ideas would get him fired at least once a week by Burns. The first shows were simply a copy of the radio format, complete with lengthy and integrated commercials for sponsor Carnation Evaporated Milk by Goodwin. However, what worked well on radio appeared forced and plodding on television. The show was changed into the now-standard situation comedy format, with the commercials distinct from the plot. Midway through the run of the television show the Burns' two children, Sandra and Ronald, began to make appearances: Sandy in an occasional voice-over or brief on-air part (often as a telephone operator), and Ronnie in various small roles throughout the 4th and 5th season. Ronnie joined the regular cast in season 6. Typical of the blurred line between reality and fiction in the show, Ronnie played George and Gracie's on-air son, showing up in the second episode of season 6 ("Ronnie Arrives") with no explanation offered as to where he had been for the past 5 years of the show. Originally his character was an aspiring dramatic actor who held his parents' comedy style in befuddled contempt and deemed it unsuitable to the "serious" drama student. When the show's characters moved back to California in season 7 after spending the prior year in New York City, Ronnie's character dropped all apparent acting aspirations and instead enrolled in USC, becoming an inveterate girl chaser. Burns and Allen also took a cue from Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz's Desilu Productions and formed a company of their own, McCadden Corporation (named after the street on which Burns' brother lived), headquartered on the General Service Studio lot in the heart of Hollywood, and set up to film television shows and commercials. Besides their own hit show (which made the transition from a bi-weekly live series to a weekly filmed version in the fall of 1952), the couple's company produced such television series as The Bob Cummings Show (subsequently syndicated and rerun as Love That Bob); The People's Choice, starring Jackie Cooper; Mona McCluskey, starring Juliet Prowse; and Mister Ed, starring Alan Young and a talented "talking" horse. Several of their good friend Jack Benny's 1953-55 filmed episodes were also produced by McCadden for CBS. The George Burns Show The George Burns & Gracie Allen Show ran on CBS Television from 1950 through 1958, when Burns at last consented to Allen's retirement. The onset of heart trouble in the early 1950s had left her exhausted from full-time work and she had been anxious to stop but couldn't say no to Burns. Burns attempted to continue the show (for new sponsor Colgate-Palmolive on NBC), but without Allen to provide the classic Gracie-isms, the show expired after a year. Wendy and Me Burns subsequently created Wendy and Me, a situation comedy in which he co-starred with Connie Stevens, Ron Harper, and J. Pat O'Malley. Burns acted primarily as the narrator, and secondarily as the advisor to Stevens' Gracie-like character. The first episode involved the middle-aged Burns watching with amusement the activities of his young upstairs neighbor on his television set, just as he would watch the Burns and Allen television show while it was unfolding to get a jump on what Gracie was up to in its final two seasons. Again as in the Burns and Allen television show, George frequently broke the fourth wall by commenting directly to viewers. The series only lasted a year. In a promotion, Burns had joked that "Connie Stevens plays Wendy, and I play 'me'." The Sunshine Boys After Gracie's death George immersed himself in work. McCadden Productions co-produced the television series No Time for Sergeants, based on the hit Broadway play; George also produced Juliet Prowse's 1965-'66 NBC situation comedy, Mona McCluskey. At the same time, he toured the U.S. playing nightclub and theater engagements with such diverse partners as Carol Channing, Dorothy Provine, Jane Russell, Connie Haines, and Berle Davis. He also performed a series of solo concerts, playing university campuses, New York's Philharmonic Hall and winding up a successful season at Carnegie Hall, where he wowed a capacity audience with his show-stopping songs, dances, and jokes. In 1974, Jack Benny signed to play one of the lead roles in the film version of Neil Simon's The Sunshine Boys (Red Skelton was originally the other, but he objected to some of the script's language). Benny's health had begun to fail, however, and he advised his manager Irving Fein to let longtime friend Burns fill in for him on a series of nightclub dates to which Benny had committed around the U.S. Burns, who enjoyed working, accepted the job. As he recalled years later: The happiest people I know are the ones that are still working. The saddest are the ones who are retired. Very few performers retire on their own. It's usually because no one wants them. Six years ago Sinatra announced his retirement. He's still working. -- George Burns Ill health prevented Benny from working on The Sunshine Boys; he died of pancreatic cancer on December 26, 1974. Burns, heartbroken, said that the only time he ever wept in his life other than Gracie's death was when Benny died. He was chosen to give one of the eulogies at the funeral and said, "Jack was someone special to all of you but he was so special to me...I cannot imagine my life without Jack Benny and I will miss him so very much."[9] Burns then broke down and had to be helped to his seat. People who knew George said that he never could really come to terms with his beloved friend's death. Burns replaced Benny in the film as well as the club tour, a move that turned out to be one of the biggest breaks of his career; his wise performance as faded vaudevillian Al Lewis earned him an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, and secured his career resurgence for good. At the age of 80, Burns was the oldest Oscar winner in the history of the Academy Awards, a record that would remain until Jessica Tandy won an Oscar for Driving Miss Daisy in 1989. Oh, God! In 1977, Burns made another hit film, Oh, God!, playing the omnipotent title role opposite singer John Denver as an earnest but befuddled supermarket manager, whom God picks at random to revive His message. The image of Burns in a sailor's cap and light springtime jacket as the droll Almighty influenced his subsequent comedic work, as well as that of other comedians. At a celebrity roast in his honor, Dean Martin adapted a Burns crack: "When George was growing up, the Top Ten were the Ten Commandments." Teri Garr costarred as Denver's wife. Burns appeared in this character along with Vanessa Williams on the September 1984 cover of Penthouse magazine, the issue which contained the infamous nude photos of Williams, as well as the first appearance of underage pornographic film star Nora Kuzma, better known to the world as Traci Lords. A blurb on the cover even announced "Oh God, she's nude!" Oh, God! inspired two sequels Oh, God! Book II (in which the Almighty engages a precocious schoolgirl (Louanne Sirota) to spread the word) and Oh, God! You Devil--in which Burns played a dual role as God and the Devil, with the soul of a would-be songwriter (Ted Wass) at stake. Burns also provided the voice of God in John Denver's TV special Montana Christmas Skies. After guest starring on The Muppet Show, Burns appeared in Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, the film based on the Beatles' album of the same name. Burns did a movie with Art Carney and Lee Strasberg in 1979 called Going in Style. Burns continued to work well into his nineties, writing a number of books and appearing in television and films. One of his last films was 18 Again!, based on his half-novelty, country music based hit single, "I Wish I Was 18 Again." In this film, he played a self-made millionaire industrialist who switched bodies with his awkward, artistic, eighteen-year-old grandson (played by Charlie Schlatter). His last feature film role was the cameo role of Milt Lackey, a 100-year-old stand-up comedian, in the 1994 comedy mystery Radioland Murders. History from Encyberpedia and OldCompany.com (old stock certificate research service)

Check