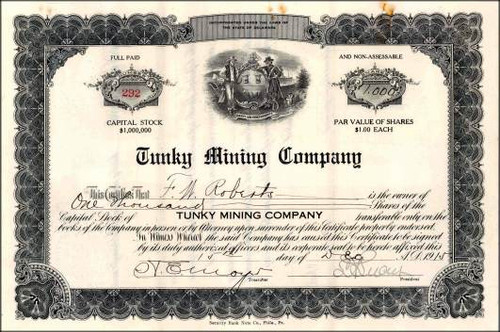

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Lake Torpedo Boat Company issued in 1915. This historic document has an ornate border around it with a vignette of an eagle. This item is hand signed by the Company's President and Assistant Treasurer and is over 90 years old.

Certificate Vignette From the beginning, building submarines in the United States resembled a tug of war between the Navy's technical bureaus and the Electric Boat Company and the Lake Torpedo Boat Company...two companies determined to retain both the initiative in submarine technology and the financial rewards it would bring. The private sector's reluctance to relinquish its advantage did not stem simply from a crass desire for monopoly and profit. Rather, the naval-industrial relationship suffered from a fundamental difference between the two contracting parties' perception of their mission. Thus, the Navy and industry built the relationship that governed submarine construction from 1916 to 1940 on a foundation of misunderstanding. This conflict was exacerbated by mobilization for war, the constantly changing state of submarine technology, the virtual monopoly of the private sector market by one prime contractor ... the Electric Boat Company...and the Navy Department's painfully slow definition of what it wanted in a submarine. By 1940, however, this relationship improved considerably. Serious efforts to resolve the conflicts between the Navy and industry and the evolution of a consensus on submarine strategy and design contributed to a mature command technology for submarines. During the inter-war period, the Bureau of Construction and Repair had decided to utilize its meager financial resources to convert its Portsmouth Navy Yard into a state-of-the-art facility for submarine design and construction. This decision contributed significantly to the demise of the Lake Torpedo Boat Company in 1924 and to the hardships borne by the Electric Boat Company...and made the bureaus more sensitive to the challenges facing private industry during a time of sharply reduced naval appropriations. The Secretary of the Navy and the technical bureaus viewed the construction of a submarine, or, indeed, any vessel, as the acquisition of a tool designed to support the Navy's activities in wartime. From this prospective, the design, construction, and reliable operation of submarines became an evolving effort to place the best naval hardware at the disposal of the fleet. No single design, no matter how well conceived, completely fulfilled all the needs of the operating forces. If a submarine did not perform well, then the development of an improved design became an urgent matter. Even when designs did not meet expectations, improvement continued. Industry did not share this unrestrained long-term commitment to development, mission, and operational support. The Electric Boat Company and the Lake Torpedo Boat Company had to weigh the costs and responsibilities of this kind of commitment against their own goals and economic well-being. Thus, they needed to define precisely their short- and long-term agreements with the Navy for submarine design and construction. The Electric Boat Company (EB) and the Lake Torpedo Boat Company (Lake) believed that if the price and the contract agreement promised both profit and growth, the quality of their products would improve and the Navy would therefore benefit. From industry's standpoint, interaction with the Navy on any given vessel ended with the Navy's acceptance of the product, thus marking fulfillment of the contract. If the contract included terms that provided for correcting performance and design deficiencies or upgrading systems, then the contractor made those changes as well. Unfortunately, submarine technology changed almost daily and the bureaus often discovered significant problems long after signing the initial contract. In such situations, the technical bureaus argued that industry had a responsibility to render the submarine safe, dependable, and effective even after the contract had expired. EB and Lake, however, found complete satisfaction in fulfilling their contract to the letter and saw no reason to commit themselves further. If the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BUC&R) or the Bureau of Steam Engineering (BUENG) wanted changes made or improvements developed and incorporated, a new agreement was in order and the Navy would have to pay for the additional services. In this environment, defining a relationship to govern the construction of a vessel whose systems and design frequently changed proved extremely difficult. The Navy's first real effort as a submarine design organization came with the S-class plans in 1916. The Navy followed up by building USS S-3 at the Portsmouth Navy Yard (PNY) to display its skill to the private sector. The potential competition bothered EB. Officials in BUC&R and BUENG feared the creation of a monopoly in the submarine construction market when EB received the T- and S-class contracts in 1916. To document their concern, these two bureaus wrote a joint memorandum to the Secretary of the Navy. They quoted EB correspondence to the effect that EB alone could produce a quality submarine; newcomers to the market would merely reduce the quality of the product. To Rear Admirals David Taylor and Robert S. Griffin in command at BUC&R and BUENG, respectively, this attitude demonstrated, "that it is the desire of the Electric Boat Company to maintain a monopoly in building submarines, and this is their major objection to the present contract and specifications, and to the preparation of plans (for the S-class) in the Department." Commitment to the fifty-one S-class submarines and the heightened importance of the submarine after 1914 led the Navy Department to challenge EB's efforts to exercise a monopoly. In 1919, Lieutenant Commander Percy T. Wright, who was in charge of the Industrial Department at the PNY, supported the decision of the Board of Inspection and Survey to expect a higher quality submarine from the PNY; this way, the Navy would gain a genuine alternative to the private sector. USS S-3 would undergo all of the tests expected of a boat built in the private yards because, in Wright's words, "the principal reason, or at least one of the principal reasons, for the Government building and designing submarines was to force private concerns to give us what we wanted and to demonstrate to them that the Government could do the job successfully." To a friend at the Bureau of Navigation, Wright conveyed the frustration of the submarine community in the face of EB's strong position in the market. With the end of the First World War, the demand for submarines had declined, and he feared the bureaus would permit EB to swallow up the few available contracts. Wright contended that in its effort to improve planning and construction, the Navy frequently underestimated its available assets. The PNY was a naval facility with an excellent design team operating in the Navy's interest. He believed that the PNY would respond far more quickly and sympathetically to any suggestions from the operating forces that might benefit the fleet. Wright lamented that some naval engineers and designers resigned at the PNY after the First World War because they assumed the bureaus would allow EB to dominate the field. He feared that, without additional support from the Navy, the PNY would lose a cadre of excellent technical people and the chance to offer EB genuine competition. Captain George W. Williams of the Submarine Section in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) shared Wright's opinions and fears. In a memorandum to the CNO in February of 1921, Williams argued in favor of awarding the first V-class fleet submarines to the PNY. He supported his case by citing EB's poor record for on-schedule construction and its general unsatisfactory performance in certain specific areas such as diesel propulsion. He also argued that the poor performance of the S-class boats built by EB had the operational forces in revolt. "Ever since our submarine Service has been in existence, there has been dissatisfaction on the part of our operating personnel with the objectives, ethics, and results of the Electric Boat Company." He questioned the firm's objection to the presence of an operational submariner on a special board considering the company's claims for extra financial compensation because of the extraordinary circumstances created by the First World War. Did the company fear the opinions of those who fought with the tools EB created? This concern, voiced by Williams and shared by many in the operational forces, illustrated the fundamental clash of viewpoints between industry and the Navy. Captain Williams observed: "The objective of the Company has been to make money, to build submarines which would pass certain specified tests; not to build efficient fighting machines." Neither Williams nor many of the operational officers relished the idea of relying on T- and S-class EB submarines at sea when their lives hung in the balance. Many within the Navy agreed with Wright and Williams that the PNY would more readily disseminate the technology and techniques of submarine construction while offering a viable alternative to EB. In June of 1918, Simon Lake wrote to the Secretary of the Navy arguing for a fair share of the last nineteen submarines in the American construction program launched in 1916. He painstakingly outlined his company's capability and plans for the future. His Bridgeport, Connecticut, construction facilities could build both 500- and 800-ton submarines. Completion of USS S-2 and USS R-21 through USS R-27 by the end of the First World War (November of 1918) would free seven 500-ton slips and one 800-ton slip for new construction. In response to the requirements of the larger S-class, Simon Lake had already laid plans for converting the 500-ton slips to accommodate the new 800-ton types, as well as allocating another 3,000 feet of waterfront for new submarine construction. The company had a staff of 1,800 skilled managers and workers ready to form the nucleus of an expanded facility that could satisfy the needs of the operating forces. Given Simon Lake's past history of poor management, this last resource did not impress the technical bureaus as much as the firm's long-term contract with the Busch-Sulzer Brothers Diesel Engine Company. Busch-Sulzer's remarkably dependable engines stood in contrast to the utterly unreliable diesels of EB's NELSECO subsidiary. With its skilled personnel, expanded facilities, and Busch-Sulzer engines, Simon Lake claimed that it could commit to ten 800-ton S-class boats immediately, and possibly thirty to forty submarines per year in the near future. Simon Lake had anticipated that the World War One submarine construction program would continue for many months. When the First World War ended in November of 1918, however, it quickly became apparent that the demand for submarines would decline and a battle would ensue for the few post-war contracts available. In February of 1920, the Navy Department ordered an evaluation of Simon Lake's potential as an effective submarine contractor. The strength of EB's virtual monopoly and the possibility of using the PNY as the primary alternative to EB, placed Simon Lake in a vulnerable position. Was this contractor worth supporting, given the promise of the PNY and the advantage of having a government-controlled lead yard, rather than another private-sector yard? The board appointed by the Secretary of the Navy to look at the situation found Lake to be small and poorly equipped by industry standards. Because Lake specialized in submarines, which constituted 98.5 percent of its output, the board expected that the firm's expertise would offset increased costs due to antiquated or inadequate equipment. On taking a closer look, however, the board discovered that Lake recorded abnormally high construction costs for its nine S-boats. The company also took four to five months longer than the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation at Quincy, Massachusetts ... the major subcontractor for EB, to build its R-class submarines. The board also criticized Lake's plant layout and management, characterizing the plant floor supervisory force as "uninspired." The board concluded "that the Lake Company in building submarines on cost-plus-percentage contracts under the present management is continuously costing the Government large sums of money without adequate return." Members suggested ways to improve Lake's ability to compete; the suggestions amounted to a complete restructuring of the company's management. The board also felt that if Lake neglected to implement its recommendations in a reasonable time, the Government should step in to assume control of the company. By April of 1920, it became evident that the Navy was more interested in developing the PNY into a shipyard on par with EB than in supporting Lake. The latter had received only a handful of the S-class submarine contracts, and after the First World War, no others seemed forthcoming. On behalf of his Bridgeport constituents, Senator Frank Brandegee, Republican from Connecticut appealed to the Secretary of the Navy. He questioned the wisdom and necessity of allowing the highly specialized workers at Lake's Bridgeport facility to lose their jobs as a result of BUC&R's preference for awarding the few available post-war submarine contracts to the Electric Boat Company and the Portsmouth Navy Yard at Kittery, Maine. Unfortunately for Lake, its performance did not give the Navy enough reason to reconsider its reliance on EB and the PNY. Lake's boats exhibited poor diving qualities, and the company had great difficulty keeping submarine construction on schedule. Captain Williams identified a major problem when he commented: "The Lake Company has been kept going by the Government and it has shown a disposition to do good work, but I understand that the company's business management has not been all that it should be and there have been long delays in the completion of work." In 1921, even as BUENG fought with EB over submarine diesels, Simon Lake wrote an open letter to Congress arguing for the survival of his company. He contended that his submarines had a high record of success in operational performance. He added that further investment in the experience and skill of his employees made sense, especially when EB displayed a lack of seasoning and competence in diesel engine design. Why should the Navy spend good money to re-engine boats purchased from EB? Lake would do the job right the first time, especially when it involved the diesel propulsion plant. In May, Captain Williams composed a memo for the CNO in which he placed the Lake case in much broader perspective. He acknowledged that the performance of the company had improved in recent days, but maintained that the influences of the Lake Torpedo Boat Company and the Electric Boat Company have been the most potent in getting Congress to authorize submarines for the Navy; but the motive behind their efforts, the desire to make money, has had its natural consequence. We got vessels, which would pass acceptance tests but were not efficient fighting machines. Williams counseled the CNO to either seek authorization for the Navy to absorb Lake's facility, or ask Congress to appropriate money for another six submarines, three of which Lake might receive if the bids were competitive. He wanted to preserve Lake in some form, if only as competition for EB, because "the prospect of a monopoly in submarine work by the Electric Boat Company is appalling." In spite of its best efforts, the Secretary of the Navy could not extract additional funds from Congress. This predicament forced naval officials to choose among supporting Lake with one or two of the scarce V-class submarine contracts, absorbing the company, or pushing it out of the market altogether by expanding the role of the Portsmouth Navy Yard. BUC&R chose the last option, wishing to provide the Navy with a viable alternative to EB, and the PNY with the opportunity to develop vital skills and experience. The diversity of EB's capabilities and its ship-construction experience permitted it to survive the long dry spell between 1921 and the contract for Submarine USS V-9 in 1931. In the interim, the company built everything from pleasure boats to machinery. The absence of the same diversity at Lake, combined with BUC&R's determination to help the PNY mature into a first-class submarine yard, assured the demise of the Lake Torpedo Boat Company. Simon Lake closed his small Bridgeport, Connecticut, firm in 1924. History from THE DEMISE OF THE LAKE TORPEDO BOAT COMPANY by Gary E. Weir, from his book (Public domain) BUILDING AMERICAN SUBMARINES 1914-1940 Researched by: Robert Loys Sminkey Commander, United States Navy, Retired

Certificate Vignette