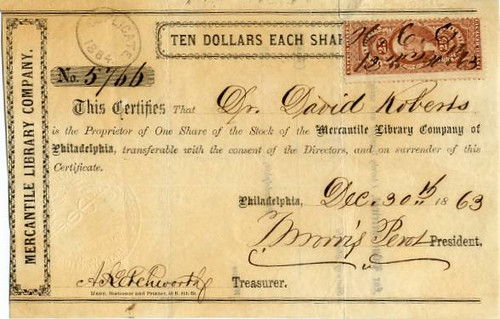

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Lawrence Manufacturing Company. This historic document was printed by the Wrence Manufacturing Company and has an ornate border around it with a postage stamp of George Washington. This item has the signatures of the Company's President, and Treasurer,and is over 147 years old. The certificate was issued to Thomas Jefferson Coolidge and hand signed by him on the back. Wear through the seal.

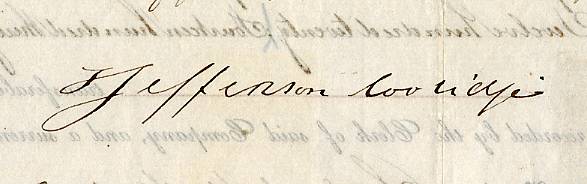

Signature of Thomas Jefferson Coolidge

Postage Stamp of George Washington MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY April 14, 1921. Thomas Jefferson Coolidge was the son of Joseph Coolidge, a merchant of Boston, seventh in descent from John Coolidge, who had settled in Watertown in 1630, and of Eleonora Wayles Coolidge, a daughter of Thomas Mann Randolph and his wife Martha, who was the eldest daughter of President Jefferson. Thus, upon the 26th day of August, 1831, the infant citizen came into being with an excellent heredity, and under auspices which could hardly have been better. His travels, which in later life were extensive on both sides of the Atlantic, began early. In 1837 he had already made his first passage and became an inmate at a boarding school near London; whence he was shortly afterwards brought home by sixty days of stormy voyaging in a packet-ship. In 1839 he re-crossed and was again placed at a boarding school, this time at Geneva, where he stayed five years. Thence he went to a gymnasium in Dresden. In 1847, after a stay of ten years abroad, he came home by a voyage of "only" twenty-four days. Forthwith after his return he entered the Sophomore Class at Harvard College, "without difficulty," as he records -- which was creditable in view of the fact that the foreign curriculum had not been arranged with any view to Harvard examination papers. He describes himself thus: "I was small, very shy, spoke English with difficulty, and was totally unfit to cope with Americans and American society. My views of my countrymen had been formed in Europe. I considered them barbarous. I believed myself to belong to a superior class, and that the principle that the ignorant and poor should have the same right to make laws and govern as the educated and refined was an absurdity. It took me many years to outgrow my priggism." In college, he says that he was quick at his lessons, but "lazy." He, however, graduated seventeenth in a class of sixty-seven students. Thus he spoke of his early days, but it may be suspected that the fine courtesy of his manners, which were his charm through life, was at least in part attributable to these early European influences; for such accomplishment would hardly have been acquired among the primitive and somewhat uncouth youths of his native city. After graduation, being, as he says, "ambitious" -- we may remember that Alexander Hamilton made precisely the like confession -- he "decided to devote himself to the acquisition of wealth;" for his observant eye seemed to tell him that money was becoming " the only real avenue to power and success, both socially and in the regard of one's fellow men." (He was at the age when clever lads are apt to go through a phase of cynicism.) He began his business career in foreign commerce, and his capacity for mercantile affairs was soon apparent. Thus he weathered the great panic of 1857, though instructed by so brief an experience; and a little later, in 1861, when the outbreak of civil dissension unsettled all business affairs down-town, he wisely foresaw the inevitable effect of the issue of irredeemable paper money, bought, as he says, "freely . . . anything which came under his hand," and later was "wise enough to stop when the currency began to improve"; whereby he saved large profits, which made him feel, as he moderately puts it, "comfortably off." Already, prior to these profitable transactions, he had been making a change in his chief occupation by wisely drawing out of foreign commerce and embarking in quite different pursuits. In 1852 he married the daughter of Mr. William Apple ton, and by this alliance there was opened to him an introduction to the great cotton-spinning industry of New England. The Boott Cotton Mills happened soon afterward to fall into a very sorry condition, and in 1858 his father-in-law pressed him to accept the presidency and to endeavor to revivify the dilapidated corporation. He had the courage to agree to this and the energy and ability to succeed in the task, with the encouraging result that at the end of about two years he had reconstructed the mill and its business. It was a tall feather in the cap of a young man who had had no previous training in this department. After the close of the Civil War he took advantage of his financial gains to go abroad with his family, and passed three years very pleasantly in foreign parts. Immediately upon his return he again resumed work, accepting the treasurership of the Lawrence Manufacturing Company. The time had already come when the question was no longer what position he could get, but what position he would take. By his able management of this corporation he further enhanced his already high reputation, so that in 1876 he had the honor of being made treasurer of the famous Amoskeag Mills, which already was, as he says, "the largest and finest cotton-spinning establishment in the United States." His brilliant conduct through long years of this noble company is familiar to us all. It is fair to say that while New England has had many dis tinguished names in her great domain of dry-goods manufacturing, and while possibly a very few among them may be rivals of Mr. Coolidge, surely no one of them can be placed above him. While mill management was Mr. Coolidge's "specialty" -- as the modem phrase has it -- he was actively concerned also in other lines of business. The generation of his middle age expended no small part of its abounding energy in developing the West, piercing it with a network of great railways, founding settlements, opening boundless plains to the farming immigrants. Mr. Coolidge, of course, had his share of this fascinating activity. For many years as a member of the Board of Directors of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Rail Road he played an influential part in the management of this most prosperous of the New England group of railways. For a while also he was president of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe road; but finding the task irksome, and moreover an obstacle in the way of the free conduct of his private business enterprises, he resigned after eighteen months of service. When the discreditable operations of Mr. Villard, mismanaging the railroads in the Northwestern section of the country, brought extensive failure and panic among those enterprises, Mr. Coolidge was called in to aid in the salvage, and he was able to rescue the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company from the wreckage. In his home neighborhood, likewise, he was prominently interested in the New England railways, and as president of the Boston & Lowell road he made the lease to the Boston & Maine road, which for a long period of years was a most satisfactory arrangement. In the science of finance also, both theoretical and applied, he was notably well informed. The government availed itself of his services on sundry occasions, most conspicuously by placing him upon the Pan-American Commission. In this task his labors were long-continued and arduous as well as eminently useful. In his own city he was for a great many years a very active member of the Directorate of the Merchants Bank, taking a very active part in its business. Neither should it be forgotten that during the same period he found time to render public service. In collaboration with Charles Dalton and William Gray, the younger, he laid out the handsome and extensive park system on the Brookline side of Boston. The character of the territory to be used was peculiar and called for handling along quite original lines. The unique and beautiful result of the scheme of driveways with their attractively developed margins of woods and water we now take for granted, but in fact it was a conception as novel and ingenious as it was successful. In politics Mr. Coolidge had no ambition whatsoever for office or preferment of any sort. But he was public-spirited, often deeply interested in political campaigns and frequently an efficient laborer therein; and upon questions of legislation falling within the range of his interests and knowledge he exercised very considerable influence. Naturally this was especially the case in regard to the tariff, and also to some extent in the days of the silver menace. In his earlier years, just before the outbreak of the Civil War, his views were much in consonance with those held by Robert C. Winthrop and other Boston men of moderate conservatism. With half of the blood in his veins flowing from Virginian sources he naturally thought the diatribes of Wendell Phillips "inflammatory" and of "pestilential influence"; yet he was desirous to see Buchanan "chastise them [the South Carolinians] instantly and severely." He was not anti-slavery, but he was strenuously pro-Union, a war-Democrat, with emphasis on the war. Later, when questions of economics became a vital line of cleavage, he took his permanent position with the Republicans. With his business interests bound up with the industries of the populous, bustling, thriving, cities and towns of New England, he could hold no other views, and he rightly conceived himself to be furthering the welfare of the community in which he lived. He played a conspicuous part in the long contest for protective duties, and thereby his ability and efficiency became more widely known in political circles. It was commonly supposed that it was in recognition of the great services rendered by him in the hard and successful struggle of 1888 that he received the appointment of Minister to France. The explanation may or may not be correct, but we may easily accept it, since it is hardly to be imagined that his eminent fitness for the post could have been the cause, it being too well known that the unhappy custom of our Government is defiantly to ignore the trifling consideration of training and probable fitness in the distribution of diplomatic positions. At any rate, whatever may have been the motive influencing the selection, it was most fortunate. Experience in diplomacy, it is true, he had not, but other essential qualifications were his in abundance -- tact and courtesy, clear, practical intelligence in affairs, a cool head and sound judgment, and an honorable integrity which very usefully won the full confidence of the French Foreign Office; further, he was even able to speak almost like a native the language of the country to which he was accredited. The Frenchmen, pleased with his coming, received with cordiality a well-bred gentleman and throughout his stay the officials with whom he had to deal manifested always a desire to meet his views and grant his requests. Some delicate points and two or three matters of considerable importance arose during his stay and were handled by him with skill, excellent sense and satisfactory result. It was unfortunate that his incumbency was cut short by the triumph of the Democrats in the Presidential election.. Only a few days after inauguration on March 4, Mr. Cleveland hastened to nominate Mr. Eustis to the post, an act hardly blameworthy according to our national customs, which certainly gave no right to so prominent a protectionist as Mr. Coolidge to expect any other fate than to be promptly and conspicuously decapitated. It was the rule of the political game. Mr. Coolidge, according to etiquette, sent in his resignation, and on April 3 received from the Secretary of State a letter accepting it. The new appointee soon crossed the water and was met by the outgoing minister with more than merely conventional kindness. Mr. Coolidge invited Mr. Eustis to breakfast, and the two discussed sundry questions of economic policies, with entire disagreement, of course, but also, of course, with entire courtesy. Mr. Coolidge then, on May 4, presented to Mr. Carnot his letters of recall, and promptly sailed for home, having, as he said, passed the happiest year of his life. With advancing years Mr. Coolidge gradually withdrew from business, not so much because interest waned as because increasing deafness finally reached such a point as practically to isolate him. The preceding brief sketch furnishes hardly a memorandum of his numerous activities. Besides the official positions which have been mentioned he held also many others somewhat less exacting and conspicuous. Further, being of a venturesome disposition and inclined to make the most of his ability in affairs, he was frequently engaged in private enterprises, generally semi-speculative, and for the most part successful, whereby he accumulated a handsome fortune. This he expended with free-handed but intelligent liberality. He gave to Harvard College the Jefferson Physical Laboratory; and to the town of Manchester the picturesque, vine-clad granite library, the work of McKim, which stands so decoratively upon the lawn on the southerly side of the beautiful North Shore road.1 Habitually, in all his ways, in his wonted cordial fashion, he respected and responded to the many obligations which lay upon one holding his social and financial position. His address was marked by an attractive friendliness, and his manner, while simple and unaffected, had a fine air of distinction. I fear that it must be admitted that he was an aristocrat; but this was not really his fault, for it was his nature and he could not help it. Yet a shrewd observer easily saw that the possessor of this courteous and pleasing exterior had also, for the appropriate occasion, a very strong and masterful will and a very resolute and persistent disposition; in fact he was quite able to face men and conquer difficulties, if either obstructed his way. He had good taste in art. He was well read in the best literature. He talked agreeably, and in writing had a direct and pleasantly simple style; and it is gratifying to be able to say of him that both in talking and in writing he had always a great respect for the English language, which he treated as well educated men always should though they sometimes do not, eschewing slang and never falling into the lingo of the newspaper writers. His Autobiography, unfortunately only "privately printed," is excellent literature as well as very interesting reading. The story of his life is a story of practically uninterrupted success, a record not unique, of course, but very unusual. This was chiefly due to the union of keen vision in practical affairs with sound judgment in all affairs. His mistakes were few and almost never important. Only once he came near to a serious peril in taking charge of the Atchison Railroad, but he escaped unhurt, and that he did so escape was due to his just appreciation of the incompatibility between the office and his own schemes -- perhaps also in part to shrewd business foresight. He certainly had great opportunities, yet not greater than some of his contemporaries who accomplished much less than he did. Opportunities of themselves achieve nothing, any more than a pen and paper write a book, or a big voice makes an orator. Mr. Coolidge clearly understood these opportunities, understood his own qualities of mind and character, understood the situation in which he found himself among his fellow-citizens both up-town and down-town, understood what life in New England had to offer. It was this intuitive and correct perception combined with an active disposition and an enterprising spirit that won for him a career which may fairly be called brilliant. His achievements were all his own. It is true that his own position and his family connections naturally brought him valuable alliances in business; also that he had able coadjutors and subordinates, who, however, were well selected by the exercise of his own insight. But the permanently operating and dominating brain power and will power were his. No man, who begins life early and ends it late, can ride through the long procession of years to enduring triumph upon the shoulders of others. Good fortune saved him from being what we call a self-made man, but he had powers which would have made him one, had he been born in a different stratum.

Signature of Thomas Jefferson Coolidge

Postage Stamp of George Washington