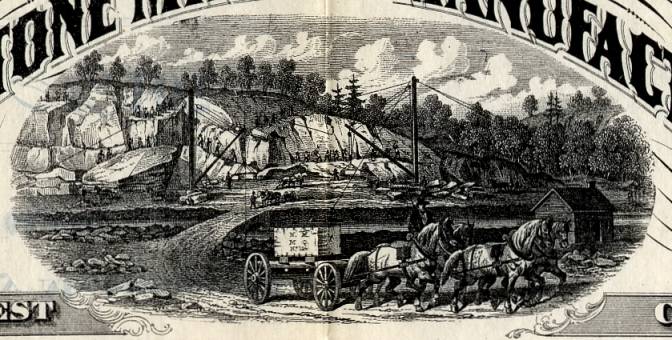

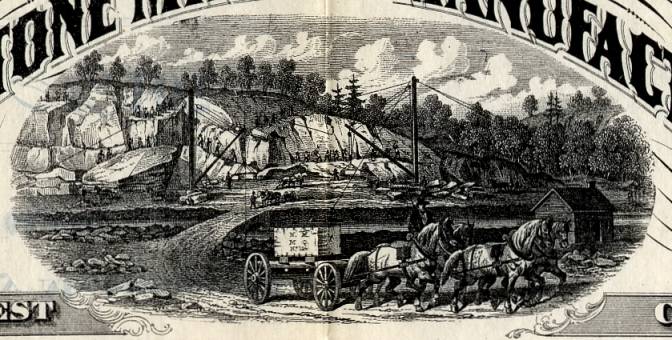

Beautiful $500 uncancelled Convertible Bond Certificate from the Maryland Freestone Mining and Manufacturing Company issued in 1870. This historic document has an ornate border around it with a scenic mining vignette with a horse drawn carriage. This item has the original signatures of the Company's President, John Kidwell and Trustees, Wm s. Huntington, Benjamin B. French and Joseph T. Brown. This bond is over 143 years old.

Certificate Vignette The Yale Review - 1906 The Maryland Freestone, Mining and Manufacturing Company, commonly called the Seneca Sandstone Company, was a promising enterprise incorporated in 1867 with such men as General Grant, Secretary Seward, and Caleb Cushing as stockholders. In 1868 Cooke and Huntington of the First National Bank, who were trustees of the Freedmen's Bank, got control, over-capitalized the stock, declared a stock dividend to the original incorporators, and issued a lot of first and second mortgage bonds, which were placed on sale, and speculation began. A loan of $51,000 was secured from the Freedmen's Bank in 1871, and $49,000 in second mortgage bonds and $20,000 in first mortgage bonds given as collateral. The second mortgage bonds were known to be worthless, and, the fact of the loan becoming public, attacks were made by newspapers upon the management. Thereupon Eaton the actuary went to Kilbourn and Evans, real estate brokers, and made an agreement with them and the Seneca Sandstone Company to change the form of the loan and thus protect the bank from unfriendly attacks. The account of the Seneca Company was then closed, the loan being transferred on the books to Kilbourn and Evans, who gave their joint note, payable in six months, supported by good collateral. This seemed well, but at the same time a curious secret agreement was made with Kilbourn and Evans, securing them against loss. This agreement was signed for the finance committee, by Huntington (of the Seneca Company), Clephane, and Tuttle, and by Eaton, the actuary. It recited the list of the securities (including $75,000 in second mortgage Seneca bonds) purporting to have been deposited by Kilbourn and Evans, and stated that in case Kilbourn and Evans did not pay the note at maturity, their note and all collateral securities were to be returned to them except the $75,000 second mortgage Seneca bonds. It was understood that the transaction was not to make Kilbourn and Evans responsible in any way; they were simply allowing the bank to use their names as an accommodation. Two years later, in 1873, the note and securities were surrendered according to agreement and only the $75,000 in worthless second mortgage bonds were left to secure the bank against loss. The actuary early in 1874 closed the Kilbourn and Evans account and charged the Seneca Company with the $51,000 and accrued interest. The $20,000 first mortgage bonds held from the Seneca Company had disappeared in 1872 in a transaction in which Kidwell, president of the Seneca Company, purchased them for $20,580, but this money was never placed in the bank. Such was the management that resulted in the ruin of the Freedmen's Bank. In 1873 the "available" fund was no longer available, the depositors had become alarmed, and three serious runs were made on the bank, taking out $1,800,000 in eighteen months. Business depression came, real estate declined in value, the bank could realize on few of its securities, and the bad loans could not be called in. Jay Cooke and Company and the First National Bank failed, and, in order to pass the crisis, the Freedmen's Bank had to sacrifice its best securities.1 As a result of the runs the bank was forced to require the depositors to give sixty days or more notice before drawing out deposits. This, though legal and provided for in the regulations, destroyed the confidence of the negroes, and few deposits were made during the latter part of 1873 and in 1874.2 Just as the deposits became large enough to pay the expenses of the bank the runs came. The Comptroller of the Currency reported in 1873 that there was serious mismanagement in the affairs of the bank, and in February, 1874, his report showed that the bank had been insolvent for a year.3 When the bank began to show signs of failure the few trustees and the officials who had deposits drew them out, while at the same time the management tried to delude the negroes into putting more money in the bank and to evade investigation by Congress. During the runs the trustees neglected the affairs of the banks; only one of them--Purvis, a negro,--came to advise and assist the actuary, who during the runs had to act on his own responsibility. The clique of speculators resigned in good time and left affairs to the incompetents and the negroes. A faction of the trustees, dissatisfied with Alvord's mismanagement, determined to bring about a change by electing Fred Douglass to the presidency in the hope that he would restore confidence and reform abuses.4 The rest of the story of the bank will be told in the next number of the Yale Review.

Seneca Sandstone Company Seneca Quarry is a historic site located at Seneca, Montgomery County, Maryland. It is located along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on the north bank of the Potomac River, just west of Seneca Creek. The quarry was the source of stone for two Potomac River canals: the Potowmack Canal (opened in 1802, and officially known as the Great Falls Skirting Canal) on the Virginia side of Great Falls; and the C&O Canal, having supplied red sandstone for the latter for locks 9, 11, 15 - 27, and 30, the accompanying lock houses, and Aqueduct No. 1, better known as Seneca Aqueduct, constructed from 1828 to 1833. Seneca red sandstone, also known as redstone, formed during the late Triassic age, 230 to 210 million years ago. Iron oxide gives the sandstone its rust color. It was prized for its ease of cutting, durability and bright color. Numerous quarries operated on the one-mile stretch of the Potomac River west of Seneca Creek. The C&O Canal provided a way for the heavy sandstone to reach the Washington, DC market, and the quarry's success is attributed to the canal. The Peter family of Georgetown, which built Tudor Place, owned the quarry from 1781 until 1866. John P.C. Peter, a great-grandson of Martha Washington, made the quarry into a commercial success by utilizing the C&O and winning the bid to supply red sandstone for the Smithsonian Castle, constructed 1847-1855. Peter built the stonecutting mill, drawing power from the adjacent canal turning basin. He also built a miniature of Tudor Place near the quarry called Montevideo, now owned by the Kiplinger family. Seneca Quarry provided the stone for hundreds of buildings around the Washington, DC area, including houses in the Dupont Circle and Adams Morgan area, the James Renwick, Jr-designed Trinity Episcopal Church (1849; demolished 1936), Luther Place Memorial Church (1873), and the D.C. Jail in the 1870s. The Government Quarry nearby provided stone for the parapet of the Union Arch Bridge (Cabin John Bridge) and the Washington Aqueduct Dam at Great Falls. After the Civil War, the Seneca Sandstone Company purchased the quarry in 1866, expanding the stonecutting mill in 1868, but went bankrupt in 1876 after financial mismanagement. It was closed for seven years. In 1883, the Potomac Red Sandstone Company reopened the quarry but only operated until 1889, when a massive flood knocked out the C&O Canal for two years. Baltimore quarry operator George Mann purchased the Seneca quarry in 1891 and operated it for the next decade. By 1901, quarrying operations had stopped as the quality of the rock diminished and Victorian architecture was no longer in vogue. Seneca Quarry is now overgrown with sycamore trees and dense brush such as wild rose, such that it is impenetrable much of the years. It is best visited in winter. The property includes ruins of the stonecutting mill and restored quarry master's house within Seneca Creek State Park, while the quarry proper, Seneca Aqueduct, and the quarry cemetery are all part of the C&O Canal NHP.The quarry falls within the boundaries of the Seneca Historic District. Seneca Quarry was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. History from Wikipedia and OldCompany.com (old stock certificate research service)

Certificate Vignette

Seneca Sandstone Company Seneca Quarry is a historic site located at Seneca, Montgomery County, Maryland. It is located along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on the north bank of the Potomac River, just west of Seneca Creek. The quarry was the source of stone for two Potomac River canals: the Potowmack Canal (opened in 1802, and officially known as the Great Falls Skirting Canal) on the Virginia side of Great Falls; and the C&O Canal, having supplied red sandstone for the latter for locks 9, 11, 15 - 27, and 30, the accompanying lock houses, and Aqueduct No. 1, better known as Seneca Aqueduct, constructed from 1828 to 1833. Seneca red sandstone, also known as redstone, formed during the late Triassic age, 230 to 210 million years ago. Iron oxide gives the sandstone its rust color. It was prized for its ease of cutting, durability and bright color. Numerous quarries operated on the one-mile stretch of the Potomac River west of Seneca Creek. The C&O Canal provided a way for the heavy sandstone to reach the Washington, DC market, and the quarry's success is attributed to the canal. The Peter family of Georgetown, which built Tudor Place, owned the quarry from 1781 until 1866. John P.C. Peter, a great-grandson of Martha Washington, made the quarry into a commercial success by utilizing the C&O and winning the bid to supply red sandstone for the Smithsonian Castle, constructed 1847-1855. Peter built the stonecutting mill, drawing power from the adjacent canal turning basin. He also built a miniature of Tudor Place near the quarry called Montevideo, now owned by the Kiplinger family. Seneca Quarry provided the stone for hundreds of buildings around the Washington, DC area, including houses in the Dupont Circle and Adams Morgan area, the James Renwick, Jr-designed Trinity Episcopal Church (1849; demolished 1936), Luther Place Memorial Church (1873), and the D.C. Jail in the 1870s. The Government Quarry nearby provided stone for the parapet of the Union Arch Bridge (Cabin John Bridge) and the Washington Aqueduct Dam at Great Falls. After the Civil War, the Seneca Sandstone Company purchased the quarry in 1866, expanding the stonecutting mill in 1868, but went bankrupt in 1876 after financial mismanagement. It was closed for seven years. In 1883, the Potomac Red Sandstone Company reopened the quarry but only operated until 1889, when a massive flood knocked out the C&O Canal for two years. Baltimore quarry operator George Mann purchased the Seneca quarry in 1891 and operated it for the next decade. By 1901, quarrying operations had stopped as the quality of the rock diminished and Victorian architecture was no longer in vogue. Seneca Quarry is now overgrown with sycamore trees and dense brush such as wild rose, such that it is impenetrable much of the years. It is best visited in winter. The property includes ruins of the stonecutting mill and restored quarry master's house within Seneca Creek State Park, while the quarry proper, Seneca Aqueduct, and the quarry cemetery are all part of the C&O Canal NHP.The quarry falls within the boundaries of the Seneca Historic District. Seneca Quarry was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. History from Wikipedia and OldCompany.com (old stock certificate research service)