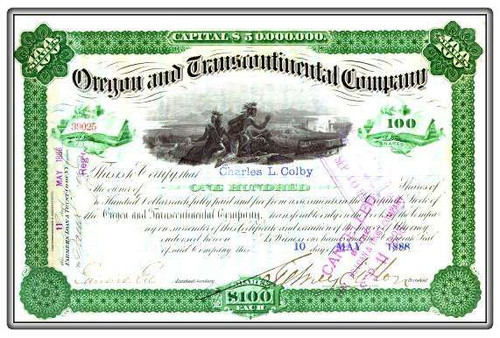

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Oregon and Transcontinental Company issued in 1888. This historic document has an ornate border around it with a vignette of two Indians over looking a city. This item is hand signed by the company's president (Sidney Dillon) and assistant secretary and is over 117 years old. SIDNEY DILLON (1812-1892). Dillon, a railroad executive, was one of America's premier railroad builders. He began his career in the industry working as a water boy on the Mohawk and Hudson, one of America's earliest railroads. He was actively involved in the construction of numerous roads, his largest being the Union Pacific, with which he became actively involved in 1865 through a stock purchased in the Credit Mobilier. As one of the principal contractors for the Union Pacific, Dillon's vast experience in the construction of railroads proved invaluable. He took part in the laying of the last rail of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, receiving one of the ceremonial silver spikes used to complete the project. Following 1870, Dillon was primarily known as a financier, becoming involved with Jay Gould in numerous ventures as well as serving on the board of directors of the Western Union Telegraph Company. Dillon, Montana was founded as originally as Terminus in 1880 with the arrival of the Utah and Northern Railroad and was renamed (1881) for Sidney Dillon, president of the Union Pacific, who directed completion of the line to Butte, 55 mi (89 km) north. Below is the eyewitness account given by Sidney Dillon, then a director and later president of the Union Pacific, od the events of driving the last spike at Promontory Point in the Transcontinential Railroad: The point of junction was the level circular valley about three miles in diameter surrounded by mountains. During all the morning hours the hurry and bustle of preparation went on. Two lengths of rail lay on the ground near the opening in the roadbed. At a little before eleven the Chinese laborers began leveling up the roadbed preparatory to placing the last ties in position. About a quarter after eleven, the train from San Francisco [he should have said from Sacramento] with Governor Stanford and his party arrived and was greeted with cheers. In the enthusiasm of the occasion there were cheers for everybody, from the president of the Union Pacific to the day laborers on the road. The two engines moved nearer each other and the crowd gathered around the open spaces. Then all fell back a little so that the view should be unobstructed. Brief remarks were made by Governor Stanford on one side and by General Dodge on the other. It was now about twelve o'clock noon, local time, or about two P.M. in New York. The two superintendents of construction, J. H. Strobridge of the Central Pacific and S. B. Reed of the Union Pacific, placed the last tie on the rails. It was of California laurel, highly polished, with a silver plate in the center bearing the following inscription: The last tie laid on the completion of the Pacific Railroad, May 10, 1869, with the names of the officers and directors of both companies. Everything was then in readiness, the word was given and "Hats Off" went clicking over the wire to the waiting crowds at New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and all principal cities. Prayer was offered by Mr. Todd, at the conclusion of which our operator tapped out: "We have got done praying. The spike is about to be presented," to which the response came back: "We understand. All ready in the East." The gentlemen who had been commissioned to present the four spikes, two of gold and two of silver, from Montana, Idaho, California, and Nevada, stepped forward and with brief appropriate remarks, discharged the duty assigned to them. Governor Stanford, standing on the north, and Dr. Durant on the south side of the track, received the spikes and put them in place. The operator tapped out, "All ready now. The spike will soon be driven. The signal will be three dots for the commencement of the blows." An instant later the silver hammers came down and, at each stroke, in all the offices from San Francisco to New York, the hammer struck the bell. The signal "Done" was received at Washington at 2:47 P.M., which was about a quarter of one at Promontory. There was not much formality in the demonstration that followed, but the enthusiasm was genuine and unmistakable. The two engines moved up until they touched each other and a bottle of champagne was poured on the last rail, after the manner of christening a ship at a launching. There were several photographs taken, in one of which General Dodge and Montague, the engineers of the two roads, are shown shaking hands. It was fitting that Strobridge, superintendent of construction on the Central Pacific, and Reed, of the Union Pacific, should be there and take a prominent part in the ceremony. For some reason never explained, Crocker was not there to meet Durant of the Union Pacific, though they represented the driving forces that had pushed the construction over the plains, mountains, and deserts for nearly 1,800 miles. The memory of General Dodge must have gone back over the years to that day in 1853, sixteen years before, when he had crossed the Missouri River with his survey party on the first investigation of the Pacific Railroad. The other great engineer, Theodore Judah, had been dead for six years, but undoubtedly he was not forgotten by those at the ceremonies. There were celebrations in many cities of the country. The telegraph company had arranged for bells to be rung in Washington, New Orleans, New York, Boston, and Omaha by the strokes of the hammer that drove the last spike. A gun was fired at Fort Point in San Francisco. In Chicago there was a parade. In New York a salute of 100 guns was fired, and the bells of Trinity Church were rung. There were celebrations at Omaha and Sacramento, and ministers throughout the nation preached sermons about the work. The importance of the great achievement was everywhere appreciated with the closing of the line at Promontory, being justly regarded as the greatest engineering and construction feat of the nineteenth century. When the ceremonies were concluded a luncheon was held in Stanford's car, and then the trains separated. There was still work to be done, but in the weeks that followed the working forces gradually melted away. Many of the men went into the operating forces of the two railroads, but most of the engineers moved to other railroads and were active in later construction. Many railroads were to be built across the continent, but never again would there be a first one. That had been completed. It was not long before the shacks that formed the town of Promontory Point disappeared and nature reclaimed the lonely valley. Since that time some attempts at farming have been made there, but today the desert mountains with their sparse growth of stunted trees look down in silence upon the historic spot where the great enterprise was culminated. A concrete monument erected there bears this inscription: COMPLETING FIRST TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILROAD DRIVEN AT THIS SPOT MAY 10TH 1869

Oregon and Transcontinental Company 1888 - signed by Sidney Dillon

MSRP:

$295.00

$195.00

(You save

$100.00

)

- SKU:

- orandtrancom

- Gift wrapping:

- Options available