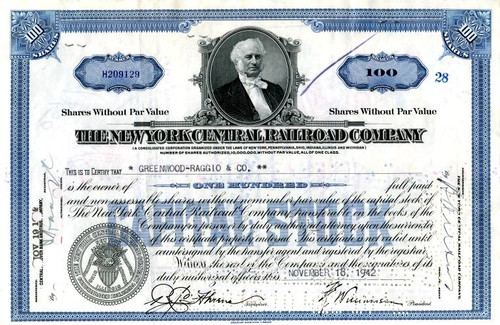

Beautiful engraved Stock Certificate from The New York Central Railroad Company issued during the 1940's-1960s for 100 shares of Common Stock. The canceled certificate has an ornate blue or brown border with a vignette in the center of the famous financier Cornelius Vanderbilt. This certificate has the printed signatures of President and Treasurer of the company. This crisp pen cancelled certificate is over 60 years old and looks great framed. Mixed brown and blue colors.

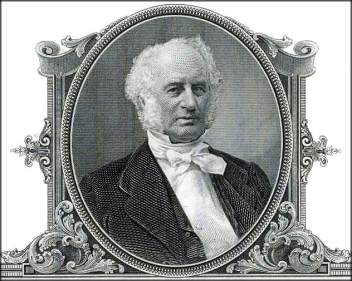

Certificate Vignette Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794-January 4, 1877) was an American steamship and railroad builder, executive, financier, and promoter. He was a man of boundless energy, and his acute business sense enabled him to outmaneuver his rivals. He left an estate of almost $100 million. Vanderbilt was born to a poor family and quit school at the age of 11 to work for his father who was engaged in boating. When he turned 16 he persuaded his mother to give him $100 loan for a boat to start his first business. He opened a transport and freight service between New York City and Staten Island for eighteen cents a trip. He repaid the loan after the first year with an additional $1,000. He was rough in manners and developed a reputation for honesty. He charged reasonable prices and worked prodigiously. The War of 1812 created new opportunities for expansion, and Vanderbilt received a government contract to supply the forts around New York. Large profits allowed him to build a schooner and two other vessels for coastal trade. Vanderbilt got his nickname "Commodore" being in command of the largest schooner on the Hudson River. By 1817 he possessed $9,000 in addition to the interest in the sailing vessels. Well on the way to fame and fortune, Vanderbilt sold his interests and turned his attention to steamboats in 1818, observing the success of Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston on the Hudson River. He went under the employ of Thomas Gibbons, operating a ferry service between New Brunswick, New Jersey and New York City, which was an important link in the New York-Philadelphia freight, mail, and passenger route. He charged his customers one dollar while other captains charged four dollars for the same trip. There was opposition from Fulton and Livingston, who claimed Vanderbilt was breaking the law as they had a legal monopoly on Hudson River traffic. They sued Gibbons, and the case reached the Supreme Court. In the famous 1824 decision, Gibbons vs. Ogden, Vanderbilt scored a victory. The Supreme Court judges nullified the navigation monopoly New York State had granted Fulton and Livingston and Vanderbilt gained control of much of the shipping business along the Hudson River. During the next eleven years, Vanderbilt made himself and Gibbons a fortune. Vanderbilt's wife also made money managing the New Brunswick halfway house where all travelers on the Gibbons line had to stay. By 1829 Vanderbilt decided to go on his own and entered the competitive service between New York and Peekskill, where he had the first of several encounters with Daniel Drew. Vanderbilt won by cutting rates to as low as 12 1/2 cents, which forced Drew to withdraw. Next he challenged the Hudson River Association in the Albany trade. After he again cut rates, the competition paid him off to move his operations elsewhere. Vanderbilt opened service to Long Island Sound, Providence, Boston, and points in Connecticut. The vessels offered the passenger not only comfort, but often luxury. By the 1840's he was running more than 100 steamboats and his company had more employees than any other business in the United States. Vanderbilt is given credit for bringing about a great and rapid advance in the size, comfort, and elegance of steamboats which were considered "floating palaces". In 1846 he launched on the Hudson the finest boat yet seen by New Yorkers and named it for himself. By the time he was 40, Vanderbilt's wealth exceeded $500,000, but he still looked for new opportunities. During the California gold rush of 1849, people traveled by boat to Panama, by land across the Isthmus on muleback, and onto steamers to the Pacific coast. Vanderbilt challenged the Pacific Steamship company by offering similar service via an overland route across Nicaragua, which saved 600 miles and cut the going price by half. This move netted him over $1 million a year. In the process he improved to some extent the channel of the San Juan River, built docks on the east and west coasts of Nicaragua and at Virgin Bay on Lake Nicaragua, and made a twelve-mile macadam road to his west coast port. He began construction of a fleet of eight new steamers and the route was two days shorter than that via Panama. He greatly reduced the New York-San Francisco passenger fare and garnered most of the traffic. He made money so rapidly, that in 1853 he announced that he was going to take the first vacation of his life. He built a sumptuously appointed steam yacht, The North Star and embarked for a triumphal tour of Europe. Before going abroad, Vanderbilt resigned the presidency of the Accessory Transit Company, and committed its management to Charles Morgan and Cornelius Garrison, who, during his absence, manipulated the stock and secured control of the company. By shrewd buying he won it back in a few months. However, the Nicaraguan government rescinded the company's charter on the grounds that its terms had been disregarded, and issued a new charter to a rival group. He sold controlling interests to the Nicaragua Transit Company, which failed to pay him. In a famous incident, he told them that the law was too slow; rather, he would ruin them. He did this in just two years by running another group of steamers. In the 1850's he dabbled in the Atlantic carrying trade competition for passenger service between New York and France with the Cunard and Collins lines. He built three vessels, one of which, the Vanderbilt, was the largest and finest he had yet constructed. It was an unprofitable venture, however, and at the beginning of the Civil War he sold his Atlantic line for $3 million. He retained the Vanderbilt, which he fitted up as a warship and turned over to the government. It has been claimed that he intended only to make a loan of the vessel, but it was interpreted as a gift. Vanderbilt liked making money more than spending it. One of the few purchases he was willing to make was his Staten Island mansion, the only place he felt truly comfortable. The New York City elite snubbed him, saying he was a rich but hopelessly vulgar man. Nearing the age of 70, Vanderbilt decided once again that the wave of the future was in another direction -- building a railroad empire. He first acquired the New York and Harlem Railroad, in the process again defeating Daniel Drew. He next acquired the rundown Hudson River Railroad, which Cornelius wanted to consolidate with the Harlem. Again Drew attempted to sell the stock short, defeat the consolidation, and make a substantial profit. But, as before, the Commodore won the battle by buying every share Drew sold, thereby stabilizing the price. Vanderbilt acquired the Central Railroad in 1867, merged it with the Hudson River Railroad by legislative act, and leased the Harlem to the new company. He spent large sums of money improving the lines' efficiency and then increased the capital stock by $42 million (which was a stockwatering operation of magnitude) and paid large dividends. In the first five years, he is said to have cleared $25 million. Vanderbilt finally hit a snag in 1867 when he attempted to gain control of the Erie Railroad, then in the hands of his old adversary, Daniel Drew. Again Vanderbilt bought all the stock offered for sale, but this time Drew threw 100,000 shares of fraudulent stock certificates on the market, which Vanderbilt continued to buy. Drew and his cohorts fled to Jersey City to avoid prosecution and bribed the New Jersey legislature to legalize the stock issue. Vanderbilt, tottering on the brink of failure, lost millions on the coup but fought back. Although the illegal stock was finally authorized by the legislature, Vanderbilt lost between $1 -$2 million and forgot the Erie. Upon the insistence of Vanderbilt's son William, he extended his line to Chicago by acquiring the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern railroads, the Canadian Southern, and the Michigan Central thereby creating one of the greatest American systems of transportation. Vanderbilt's influence on national finance was stabilizing. When the panic of 1873 was at its worst, he announced that the New York Central was paying out millions of dividends as usual, and let contracts for the building of the Grand Central Terminal in New York City, with four tracks leading from it, giving employment to thousands of men. He saw to it, however, that the city paid half the cost of the viaduct and open-cut approaches to the station. By 1875, his New York Central Railroad controlled the lucrative route between New York and Chicago. Vanderbilt was never known for philanthropic activities. His only unsolicited contributions were $50,000 for the Church of the Strangers in New York City and $1 million to Central University, which then became Vanderbilt University. Upon his death, he was the richest man in the United States. Cornelius Vanderbilt left the bulk of his fortune - $95 million - to his son William. A footnote to the Vanderbilt fortune: William Vanderbilt is remembered for his remark, "The public be damned," when asked by a reporter whether railroads should be run for the public benefit.

Certificate Vignette