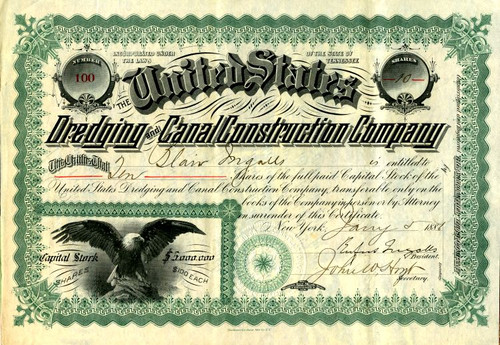

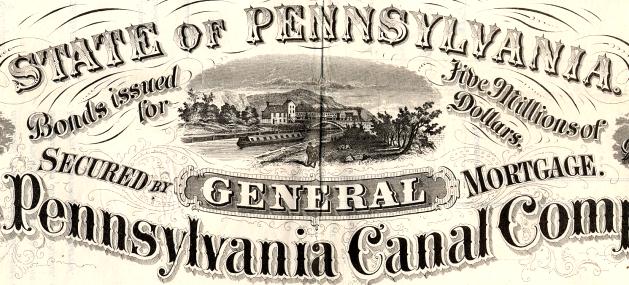

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Pennsylvania Canal Company issued in 1870. This historic document has an ornate border around it with a vignette of a barge floating down the canla with train passing over a bridge. This item is hand signed by the company's president and secretary and is over 145 years old. Stamped Cancelled on signatures.

Certificate Vignette In 1866 the Pennsylvania Railroad Company sold to the Pennsylvania Canal Company that part of its canal property that was not abandoned, amounting to one hundred and seventy-eight miles. The consideration was $2,750,000, and of this amount $1,000,000 was reckoned as being the value of the canals when first purchased by the railroad in 1857. The companies' reports seem to show that this sale was made to avoid further payments to the State, and that the State received only this sum, $1,000,000, instead of the $7,500,000 as at first agreed. The Pennsylvania Canal Company acquired a majority of the shares of the West Branch Canal Company in 1867, and operated the canals of that company (Susquehanna and West Branch canal) under a lease after 1869. The Wyoming Canal Company was absorbed by the Pennsylvania Canal Company in 1869. In 1870 the property of the Wiconisco Canal Company was obtained as a result of a judgment, and thereafter all these canals were operated as a single property. In 1870 the canals of the Erie Canal Company were acquired by forced sale by the Pennsylvania Company and were operated through the season of 1871, when they were abandoned. In 1872 the canals in operation under the control of the Pennsylvania Canal Company were reported as follows: Columbia-Wilkesbarre 151 miles Junction-Williamsburg 113 miles Northumberland-Farandsville 82 miles Clarks Ferry-Millersburg 12 miles Total 358 miles The prism was 40 to 60 feet at water-surface, 24-34 at bottom and from 4 to 6 ¼ feet deep. The locks were as follows: Cut stone 61 Wood and rubble 46 Wood 25 Total 132 Besides these lift-locks there were fourteen stop-locks, sixteen guard-locks, and four weigh-locks. There were, on the entire system, twenty-six dams, sixty-eight aqueducts, and eighteen miles of slack water. At this date the average capacity of the boats was one hundred and twenty tons each, and the average tonnage on the canals was a little less than one million tons yearly. The canals of the western division were entirely abandoned in 1865 and after 1872 the number of miles operated decreased steadily. In 1875 the canal mileage of this system had decreased to three hundred and twenty-four miles. Again, in 1901, all except one hundred and one-half miles of the canals of this system were abandoned. In 1903 only forty-three miles remained and in 1904, this great system of Pennsylvania canals was wholly abandoned. The Delaware Division canal which is not included in the above system, but which is under the control of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, remains to-day a sole representative of the original system of State canals. John Brown's Failures As with everything John Brown did, he approached business with an unyielding insistence that his way was the right way. He was consumed by his work; he had no hobbies, no romance. He gave orders, said a younger brother, like "a King against whom there is no rising up." But Brown's inflexibility -- exacerbated by poor judgment and bad luck - would lead to a lifetime of business failures and broken dreams. As a young man, Brown worked for his father, learning the business of running a tannery. But he was too ambitious and headstrong to take orders from anyone, even his father. At age 17 he left to start a competing tannery of his own. At first he prospered. In 1826 he built an even larger tannery in Pennsylvania. He employed fifteen men. He was respected as a businessman and leader in the community. But Brown began to feel the strains of providing for his ever expanding family. His first wife, Dianthe, had died from a fever. He remarried a year later to sixteen-yezr-old Mary Day who would look after his five children and bear thirteen of her own. By spring of 1835 Brown was desperate for cash. He borrowed heavily. Unable to support his family, he began looking for ways to make money fast. Like many Americans, he wanted to be part of the great adventure that was transforming the nation at that time. Inventions like the telegraph and steam-powered locomotive were changing the world. The success of the Erie Canal created a "canal boom." Thousands of dollars were being made in land speculation. Brown convinced family and friends to entrust him with their money. He anticipated the prosperity a new canal would bring in Ohio -- the new towns and trading centers - and bought land, spending thousands of dollars. It looked like a sure thing; the first Ohio canal had sent land values skyrocketing. Land that had originally sold for $11 an acre was going for up to $7,000 for a 10 acre lot. All Brown and his investors had to do was sit back and wait for their canal to arrive. Unfortunately, a great economic downturn was about to rock the nation. "The panic of 1837 was the largest bankruptcy that the United States had ever had," comments historian, James Stewart. "Brown was swept along in a current of default and collapse. Brown would be a typical story of someone who invested, as thousands did, and lost thousands, as thousands did...." The Pennsylvania Canal Company changed their plans, making Brown's properties nearly worthless. His business associates wanted to sell, but Brown stubbornly told them to hold on, that the market would recover. Things only got worse. Creditors foreclosed and dragged him into court. Brown was found to be negligent and shortsighted in his business transactions, but all agreed was not dishonest. A business acquaintance described him as having "fast, stubborn and strenuous convictions that nothing short of mental rebirth could ever have altered." With his land scheme in pieces, he tried breeding sheep. He started another tannery, bought and sold cattle. Each time he failed. But Brown stubbornly refused to give up. Although England had enough wool to export some to America, Brown believed he could sell American wool there. He traveled to London -- and promptly lost $40,000. In 1842 Brown applied for bankruptcy. Lawsuits against him piled up in four states. In the final settlement, he lost almost everything he owned. He was left only with living essentials, and eleven Bibles and Testaments. Brown's temperament and business acumen did not make a good combination. When things went bad, he would place his fate in the hands of divine providence and hope that his creditors shared his faith. Surprisingly, those he owed most seemed most forgiving. Sources: "John Brown's Holy War" show text "To Purge This Land with Blood" Stephen Oates

Certificate Vignette