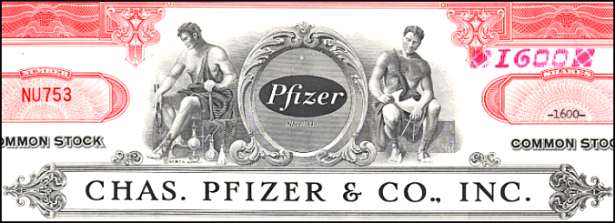

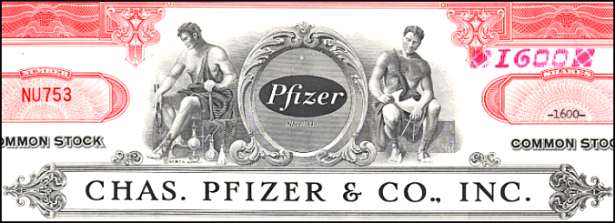

Beautifully engraved Certificate from the famous Pfizer - Chaz Pfizer & Co. - Scarce Red Color issued in 1959 - 1960. The red color certificate was issued for shares over 100 and is much more scarce than the other colors. This historic document was printed by the Security-Columbian Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of two allegorical men on both sides of the company's logo. This item has a printed signature of the Company's Chairman ( John McKeen ) and Secretary and is over 44 years old.

Certificate Vignette The company was founded in 1849 by two immigrants. They are the people who produced life saving surgical chemicals used in the Civil War. They were the first to discover how to mass produce the world's first miracle drug--penicillin. Cousins Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhart emigrated from Ludwigsburg, Germany, in the mid-1840s. Though they came from well-to-do families, the cousins yearned for adventure, and they saw America as a land of opportunity. In Germany, Charles Pfizer had learned chemistry as an apothecary's apprentice, while Erhart became a confectioner -- a trade he learned from his uncle, Carl Frederick Pfizer. In America, the cousins united their skills and in 1849 founded a chemical firm, Charles Pfizer & Company. The Company began operations in the Williamsburg community of Brooklyn, New York. From the start, the Company sought to chart new courses. The cousins saw an opportunity in manufacturing specialty chemicals that were not otherwise produced in America, thus gaining a competitive advantage over expensive imports. The cousins' first breakthrough was a medical treatment, a harbinger of things to come. They decided to make santonin -- a treatment for parasitic worms that was effective but intensely bitter -- more palatable by blending it with almond-toffee flavoring and shaping it into a candy cone. The product was an immediate success. Within ten years, the Company was manufacturing more than a dozen other chemicals and medicinal preparations, including borax, camphor, and iodine. Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhart were entrepreneurs, with enterprising spirits and a willingness to take risks to see their dreams fulfilled. They were at the forefront of a new industry, in a new country. Industrialization, transportation systems, technology, and medical advances opened up a world of opportunity. Pfizer and Erhart were not ones to sit back and let the world change without them. They seized the moment. Pfizer grew and diversified through the latter half of the 19th century, gaining a reputation for high-quality products, technical prowess, reliability, and customer focus. But the Company was vulnerable to price increases and supply shortages because it depended on imports. When the raw material supply needed to make citric acid, Pfizer's most important product, dried up during World War I, the Company had two options: close its doors or find another way to get the job done. For decades, citric acid was Pfizer's most popular product. Originally processed from the juice of lemons, limes, and sour oranges, citric acid was used primarily for medicinal purposes, as well as for foods, soft drinks, cleaning fluids, and industrial processes. Until 1880, most of the raw material was imported from Italy, but political instability and unpredictable weather there led to extreme price fluctuations and an unreliable supply. When World War I erupted in 1914, the Italian imports stopped altogether and Pfizer pursued other supply sources. A new era dawned in 1917, when Dr. James Currie joined Pfizer. As a government food chemist, Currie had been studying fermentation in cheese-making and discovered that one of the by-products was citric acid. Other scientists had noticed this decades earlier, but they did not realize the potential. Currie began a series of fermentation experiments using sugar and bread mold and was able to produce small amounts of crude citric acid. But manufacturing large quantities of the substance was quite another matter. He came to Pfizer to pursue this challenge. At Pfizer, Currie and an assistant, Jasper Kane, worked in extreme secrecy. They gradually improved the procedure, developing a process known as SUCIAC -- Sugar Under Conversion Into Acid Citric. The Company gambled on the process, taking a calculated risk in turning over its still-profitable borax and boric acid production facilities to SUCIAC. In time, SUCIAC production began to outperform conventional extraction from citrus products, and by 1929 Pfizer no longer needed any imported citrus product at all. Kane went on to develop a new deep-tank fermentation method using molasses rather than refined sugar as raw material. No one yet knew the implications, but it was this process that ultimately unlocked the secret for large-scale production of penicillin. For more than three million years, the human race battled nonstop against microbes, or, as most people know them, germs. And for millennia, microbes won. Waves of plague, typhus, influenza, and other infectious diseases left death and suffering in their wake. Finally, in 1928, Dr. Alexander Fleming's discovery of penicillin signaled the dawn of modern medicine and offered real hope in the battle against infection. But penicillin couldn't be manufactured in large enough quantities to help people until Pfizer pioneered its mass production, just in time to save the lives of countless World War II servicemen. In 1928, when bacteriologist Alexander Fleming discovered the germ-killing properties of the "mold juice" secreted by penicillium, he knew that it could have profound medical value. But Fleming could not make enough penicillin to be useful in practice, and his discovery was dismissed as a mere laboratory curiosity. A decade later, a team of scientists at Oxford University rediscovered Fleming's work. Armed with increasing evidence of the remarkable powers of penicillin, but unable to engage British companies due to the country's involvement in World War II, the Oxford scientists sought help in America. In 1941, Pfizer's John Davenport and Gordon Cragwall attended a symposium at which researchers from Columbia University, building on the work of British scientists, presented clear data that penicillin could effectively treat infections. Inspired by the possibilities, the two men offered Pfizer's assistance. That same year, Pfizer was among the companies responding to a government appeal to join a high-stakes race to see which company would develop a way to mass-produce the world's first "wonder drug." Beginning with fermentation experiments conducted with the team at Columbia University, Pfizer would take enormous risks over the next three years in devoting its energies to penicillin production. The substance was highly unstable, and initial yields were discouragingly low. But Pfizer was determined to succeed in the quest to mass-produce this lifesaving new drug. In the fall of 1942, Pfizer scientist Jasper Kane suggested a radically different approach, proposing that the Company attempt to produce penicillin using the same deep-tank fermentation methods perfected with citric acid. This was tremendously risky because it would require Pfizer to curtail the production of citric acid and other well-established products while it focused on the development of penicillin. It could also place the Company's existing fermentation facilities in danger of becoming contaminated by the notoriously mobile penicillium spores. In a small room in the Brooklyn plant, Pfizer's senior management met to weigh the options -- and took the leap. They voted to invest millions of dollars, putting their own assets as Pfizer stockholders at stake, to buy the equipment and facilities needed for deep-tank fermentation. Pfizer purchased a nearby vacant ice plant, and employees worked around the clock to convert it and perfect the complex production process. The plant was up and running in just four months, and soon Pfizer was producing five times more penicillin than originally anticipated. Recognizing the superiority of the Pfizer process and desperate for massive quantities of penicillin to aid in the war effort, the U.S. government authorized 19 companies to produce the antibiotic using the Company's deep-tank fermentation techniques, which Pfizer had agreed to share with its competitors. Despite their access to Pfizer's technology, none of these companies could come close to Pfizer's production levels and quality. Indeed, Pfizer produced 90 percent of the penicillin that went ashore with Allied forces at Normandy on D-Day in 1944 and more than half of all the penicillin used by the Allies for the rest of the war, helping to save countless lives. The race to mass-produce penicillin was over. Pfizer had emerged victorious, but the real winners were the millions of people who were to benefit from the wonder drug. Penicillin was a turning point in human history -- the first real defense against bacterial infection. In 1943, the U.S. government mandated that all penicillin be dedicated to the war effort except in special circumstances. But word of the new drug was spreading quickly, and Pfizer found itself besieged with requests for the drug from desperate families with dying relatives. John Smith, Pfizer President and Chairman of the Board, faced a particularly difficult dilemma when Dr. Leo Loewe of nearby Brooklyn Jewish Hospital pleaded with him for penicillin to treat a young girl who was dying of subacute bacterial endocarditis. Smith agreed to go see her, and before long both he and his successor, John McKeen, visited the dying little girl. Perhaps she reminded Smith of his own young daughter, who had died of infection before penicillin was available. Loewe received his penicillin. Although penicillin was not thought to be an effective treatment for subacute bacterial endocarditis, Loewe's intravenous drip worked, and the little girl recovered. The medical establishment was shocked, but Loewe had a simple explanation: Doctors had not been using enough penicillin. He had dripped forty thousand units into his small patient. Smith continued to supply Loewe with penicillin until he was ordered by the government to ship all penicillin supplies directly to the military. But that order didn't stop people from getting sick, and Loewe continued to ask Smith for lifesaving penicillin. Smith soon discovered a solution. The Company was allowed eight million units of penicillin each month for its own uses, presumably research. Smith shipped much of this to Loewe. At one point, the National Defense Research Council (NDRC) investigated Smith and Loewe, suspecting that the doctor was using penicillin intended for the military to cure his patients. Although there was some discussion about bringing charges against Smith, he was acting within the regulations. And eventually, following Loewe's dramatic success, the NDRC declared penicillin an effective treatment for subacute bacterial endocarditis. For its first 100 years, Pfizer sold its products in bulk through other companies, which packaged them under their own brand names. But when Pfizer discovered a new antibiotic in the late 1940s, the Company knew the time was right to step out on its own. Recognizing that penicillin was only the beginning of an era of medical breakthroughs in which Pfizer could play a major role, the Company's scientists began an intensive quest to find new organisms to fight disease. Emerging theories suggested that bacteria-fighting organisms would be found in soil, so the Company launched a worldwide soil collection and testing program. Pfizer solicited and received 135,000 soil samples and conducted more than 20 million tests. Said one of the researchers, "We got soil samples from the bottom of mine shafts; we got soil from the bottom of the ocean. We got soil from the desert; we got it from the tops of mountains and the bottom of mountains and in between." Pfizer eventually hit "pay dirt," finding a substance that proved effective against a wide range of deadly bacteria. It became the first product ever to be discovered and developed exclusively by Pfizer scientists and was named Terramycin®, because it came from the earth (terra, in Latin). One week before the patent was issued, Pfizer CEO John Smith died. But from his deathbed, he gave this advice to his successor, John McKeen: "If anything comes of this antibiotic soil-screening program, don't make the mistake we made with penicillin and hand it over to other companies. Let's sell it ourselves. Go into the pharmaceutical business." Pfizer's management met and agreed to "put it on the line." They honored Smith's wishes. When Terramycin® was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on March 15, 1950, eight specially trained Pfizer pharmaceutical salesmen were waiting for word at pay phones across the nation. They spread out to get inventory to wholesalers and to educate physicians about Pfizer's first proprietary pharmaceutical product -- and were the vanguard of a sales and marketing organization that would come to be recognized as the best in the industry. A formidable new pharmaceutical company had been born. Since Pfizer's penicillin production breakthrough more than 50 years ago, the Company has played a leading role in the discovery, development, and marketing of anti-infective medicine. In December 1997, the Company received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for Trovan®, the latest entry in a proud tradition of innovative Pfizer products that includes Terramycin®, Geopen®, Cefobid®, Sulperazon®, Unasyn®, Vibramycin®, Diflucan®, and Zithromax®. As Pfizer Chairman and CEO William C. Steere, Jr., stated at the Trovan® training meeting, "The names of our products read like an anti-infective Hall of Fame." Trovan® was approved for 14 indications by the FDA, the most ever for any antibiotic at first approval, and received European marketing approval in June 1998. The success that the product is enjoying in the marketplace -- and the reemergence of infectious disease as a significant global health problem -- has affirmed the Company's decision to maintain an intensive antibiotics discovery and development program throughout the 1970s and 1980s, when many other pharmaceutical companies had all but abandoned their programs. While the pharmaceuticals business was John Smith's legacy, John McKeen and Jack Powers can be credited as the visionaries who saw Pfizer's future as a global enterprise. Starting with a network of sales agents in a few countries, in the 1950s Pfizer began to establish offices, subsidiaries, and partnerships around the world. With its expanding portfolio of innovative products, Pfizer soon became an international powerhouse. Success came from the same qualities that propel Pfizer today -- business acumen and competitiveness coupled with a relentless drive to bring lifesaving products to people around the world. With a number of U.S. pharmaceutical companies entering the penicillin production business after World War II, Pfizer found itself facing hostile market conditions in its home territory. But while other companies copied Pfizer's manufacturing techniques, the Company's competitive spirit proved much harder to duplicate. Recognizing that the extensive use of penicillin during the war had made Pfizer a well-known name overseas, and knowing that war-ravaged, "I WILL NEVER FORGET THOSE DAYS. WE WERE UNENCUMBERED BY EXPERIENCE, SO WE DIDN'T REALIZE THE PROBLEMS. THERE WAS NOBODY TO TELL US, 'YOU CAN'T DO IT.' TAKING CHANCES AND GAMBLES MADE IT A JOYOUS TIME." - John J. Powers, Jr., Chairman of the Board, Chief Executive Officer, and President John "Jack" Powers, Jr., then assistant to Pfizer President John McKeen, led the charge. At a long Saturday meeting in 1950, he outlined his ambitious plans for what would become the Pfizer International Division to the handful of staff members who would work to put the Company on the map. Powers challenged the team to achieve $60 million in international sales a year -- a substantial sum in those days -- and urged them to "study the economy; establish proper contacts with government officials; learn the language, history, and customs; and hire local employees wherever possible." It was a simple formula that would prove to be remarkably successful. As Pfizer opened an increasing number of offices abroad, Powers divided the world into four regions -- Europe, Western Hemisphere, Far East, and Middle East -- each to be run by a regional director at Headquarters. But the real action was taking place far away from New York, as International staffers unearthed one business opportunity after another in countries ranging from Argentina to Australia and Belgium to Brazil. While other companies kept their international employees on a short leash, Pfizer gave its overseas people tremendous autonomy, enabling them to make important decisions immediately, rather than waiting weeks, or even months, for the home office to respond. Though the Company initially invested only a modest sum in International, the division soon became profitable enough to finance its own expansion into manufacturing, helping to meet the growing demand for Pfizer products that the Company was now enjoying in virtually every part of the world. By 1957 Pfizer International exceeded the $60 million sales goal, placing the Company well ahead of its US competitors. Pfizer's commitment to -- and success in -- international markets continues to this day. In 1997, Pfizer's revenues outside the United States totaled $5.6 billion -- a full 45 percent of the Company's total revenues for the year -- and Pfizer products are available in more than 150 countries. In any language, Pfizer's decision to expand overseas has spelled success. The second half of the 20th century has been an era of unprecedented advances in medical discovery, and Pfizer has made major contributions through the development of cutting-edge medicines. Fueled by the revenues generated by innovative marketing and sales teams, and guided by then-Chairman Edmund T. Pratt, Jr., Pfizer in the 1970s committed to long-term investment in research that would pay off years later. In the 1960s and 1970s, Pfizer continued to develop and market new pharmaceuticals. Novel antibiotics were followed by drugs to treat arthritis, diabetes, depression, heart disease, fungal infections, and other ailments. Marketing and sales had established a reputation for creativity and innovation. In 1971, the Company established the Central Research Division, combining Pfizer's disparate research organizations. Edmund T. Pratt, Jr., who became Chairman and CEO in 1972, believed that this increased commitment to pharmaceutical research would pay off handsomely and plowed 15 to 20 percent of sales into research, ramping up productivity to match the industry's leading players. Ultimately Pfizer's research investments paid off. In 1970 in Sandwich, England, research began on fluconazole. It was introduced in the United States in 1990 as Diflucan® and is now the world's most-prescribed antifungal. Similarly, in the late 1970s research started on amplodipine. It was introduced in the United States in 1992 as Norvasc® and today is the world's most-prescribed antihypertensive. These successes were based not only on heavy dollar investment, but also on creative research strategies, such as the shift of emphasis from fermentation research to synthetic organic chemicals as potential sources of new medicines. In addition, the use of interdisciplinary teams encouraged cross-fertilization of ideas, making research even more productive. In addition to pushing Pfizer to invest in research, Chairman Pratt also led the battle for public policies that would encourage all companies to devote resources to R&D. He committed extensive personal and Company effort to the ongoing fight for intellectual property protection. Recognizing that patent protection would be crucial, not only to Pfizer's future, but to encouraging innovation and progress around the globe, Pratt became an early pioneer for intellectual property rights. Through years of personal leadership and, ultimately, as chairman of the President's Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations during the Carter and Reagan administrations, Pratt "was instrumental in transforming intellectual property from a lawyer's specialty into an international trade issue of great concern to governments around the world," according to a Harvard Business School case study. When he retired in 1992, Pratt left Pfizer with an exceptional pipeline of products in development and a legacy of engagement in public policy issues that would help to shape the future of medicine.

Certificate Vignette