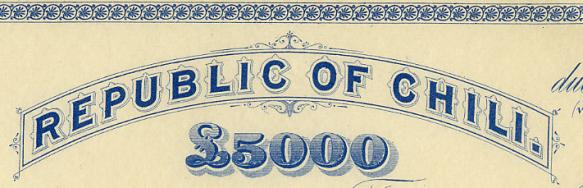

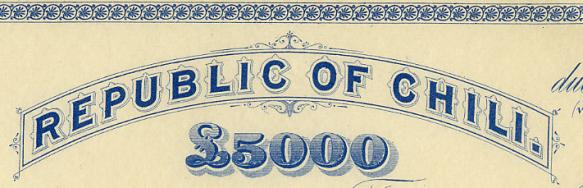

Beautifully engraved RARE 5,000 Pound Treasury Bill Specimen Certificate from the Republic of Chili (Chile) issued in 1896. This historic document was printed by Bradbury, Wilkinson and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of the name on top center. This item is an unusual error specimen that says "Republic of Chili" vs "Republic of Chile". This is the only example of this we have scene and it may be unique. This item is over 110 years old.

Certificate Vignette The Republic of Chile (Spanish: República de Chile ▶ (help·info)) is a country in South America occupying a long coastal strip between the Andes mountains and the Pacific Ocean. It borders with Argentina to the east, Bolivia to the northeast and Peru to the north. History Main article: History of Chile About 10,000 years ago, migrating Native Americans settled in fertile valleys and along the coast of what is now Chile. The Incas briefly extended their empire into what is now northern Chile, but the area's remoteness and the fierce opposition of the native population prevented extensive settlement. Pedro de ValdiviaIn 1520, while attempting to circumnavigate the earth, the Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan, discovered the southern passage now named after him, the Straits of Magellan. The next Europeans to reach Chile were Diego de Almagro and his band of Spanish conquistadors, who came from Peru in 1535 seeking gold but were turned back by the local population. The Spanish encountered hundreds of thousands of Indians from various cultures in the area that modern Chile now occupies. These cultures supported themselves principally through slash-and-burn agriculture and hunting. The first permanent European settlement, Santiago, was founded in 1541 by Pedro de Valdivia, one of Francisco Pizarro's lieutenants. Although the Spanish did not find the extensive gold and silver they sought, they recognized the agricultural potential of Chile's central valley, and Chile became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Conquest of the land that is today called Chile took place only gradually, and the Europeans suffered repeated setbacks at the hands of the local population. A massive Mapuche insurrection that began in 1553 resulted in Valdivia's death and the destruction of many of the colony's principal settlements. Subsequent major insurrections took place in 1598 and in 1655. Each time the Mapuche and other native groups revolted, the southern border of the colony was driven northward. The abolition of slavery in 1683 defused tensions on the frontier between the colony and the Mapuche land to the south, and permitted increased trade between colonists and Mapuches. The drive for independence from Spain was precipitated by usurpation of the Spanish throne by Napoleon's brother Joseph, in 1808. A national junta in the name of Ferdinand--heir to the deposed king--was formed on September 18, 1810. The junta proclaimed Chile an autonomous republic within the Spanish monarchy. A movement for total independence soon won a wide following. Spanish attempts to reimpose arbitrary rule during what was called the Reconquista led to a prolonged struggle. Bernardo O'HigginsIntermittent warfare continued until 1817, when an army led by Bernardo O'Higgins, Chile's most renowned patriot, and José de San MartÃn, hero of Argentine independence, crossed the Andes into Chile and defeated the royalists. On February 12, 1818, Chile was proclaimed an independent republic under O'Higgins' leadership. The political revolt brought little social change, however, and 19th century Chilean society preserved the essence of the stratified colonial social structure, which was greatly influenced by family politics and the Roman Catholic Church. The system of presidential absolutism eventually predominated, but wealthy landowners continued to control Chile. Toward the end of the 19th century, the government in Santiago consolidated its position in the south by ruthlessly suppressing the Mapuche Indians, finally completing the conquest begun more than three centuries earlier. In 1881, the government signed a treaty with Argentina confirming Chilean sovereignty over the Strait of Magellan. As a result of the War of the Pacific with Peru and Bolivia (1879-83), Chile expanded its territory northward by almost one-third, eliminating Bolivia's access to the Pacific, and acquired valuable nitrate deposits, the exploitation of which led to an era of national affluence. The Chilean Civil War in 1891 brought about a redistribution of power between the President and Congress, and Chile established a parliamentary style democracy. However, the Civil War had also been a contest between those who favored the development of local industries and powerful Chilean banking interests, particularly the House of Edwards who had strong ties to foreign investors. Hence the Chilean economy partially degenerated into a system protecting the interests of a ruling oligarchy. By the 1920s, the emerging middle and working classes were powerful enough to elect a reformist president, Arturo Alessandri Palma, whose program was frustrated by a conservative congress. Alessandri Palma's reformist tendencies were partly tempered later by an admiration for some elements of Mussolini's Italian Corporate State. In the 1920s, Marxist groups with strong popular support arose. A military coup led by General Luis Altamirano in 1924 set off a period of great political instability that lasted until 1932. The longest lasting of the ten governments between those years was that of General Carlos Ibáñez, who briefly held power in 1925 and then again between 1927 and 1931 in what was a de facto dictatorship, although not really comparable in harshness or corruption to the type of military dictatorship that has often bedeviled the rest of Latin America, and certainly not comparable to the violent and repressive regime of Augusto Pinochet decades later. By relinquishing power to a democratically elected successor, Ibáñez del Campo retained the respect of a large enough segment of the population to remain a viable politician for more than thirty years, in spite of the vague and shifting nature of his ideology. When constitutional rule was restored in 1932, a strong middle-class party, the Radicals, emerged. It became the key force in coalition governments for the next 20 years. During the period of Radical Party dominance (1932-52), the state increased its role in the economy. In 1952, voters returned Ibáñez, now reincarnated as a sort of Chilean Perón, to office for another 6 years. Jorge Alessandri succeeded Ibáñez in 1958, bringing Chilean conservatism back into power democratically for another term. The 1964 presidential election of Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Montalva by an absolute majority initiated a period of major reform. Under the slogan "Revolution in Liberty," the Frei administration embarked on far-reaching social and economic programs, particularly in education, housing, and agrarian reform, including rural unionization of agricultural workers. By 1967, however, Frei encountered increasing opposition from leftists, who charged that his reforms were inadequate, and from conservatives, who found them excessive. At the end of his term, Frei had accomplished many noteworthy objectives, but he had not fully achieved his party's ambitious goals. In 1970, Senator Salvador Allende Gossens, a Marxist physician and member of Chile's Socialist Party, who headed the "Popular Unity" (UP or "Unidad Popular") coalition of the Socialist, Communist, Radical, and Social-Democratic Parties, along with dissident Christian Democrats, the Popular Unitary Action Movement (MAPU), and the Independent Popular Action, won a plurality of votes in a three-way contest. Despite pressure from the government of the United States, the Chilean Congress, keeping with tradition, conducted a runoff vote between the leading candidates, Allende and former president Jorge Alessandri and chose Allende by a vote of 153 to 35. Frei refused to form an alliance with Alessandri to oppose Allende, on the grounds that the Christian Democrats were a workers party and could not make common cause with the oligarchs. Allende's program included advancement of workers' interests; a thoroughgoing implementation of agrarian reform; the reorganization of the national economy into socialized, mixed, and private sectors; a foreign policy of "international solidarity" and national independence; and a new institutional order (the "people's state" or "poder popular"), including the institution of a unicameral congress. The Popular Unity platform also called for nationalization of foreign (U.S.) ownership of Chile's major copper mines. An economic depression that began in 1967 peaked in 1970, exacerbated by capital flight, plummeting private investment, and withdrawal of bank deposits by those opposed to Allende's socialist program. Production fell and unemployment rose. Allende adopted measures including price freezes, wage increases, and tax reforms, which had the effect of increasing consumer spending and redistributing income downward. Joint public-private public works projects helped reduce unemployment. Much of the banking sector was nationalized. Many enterprises within the copper, coal, iron, nitrate, and steel industries were expropriated, nationalized, or subjected to state intervention. Industrial output increased sharply and unemployment fell during the Allende administration's first year. Other reforms undertaken during the early Allende period included redistribution of millions of hectares of land to landless agricultural workers as part of the agrarian reform program, giving the armed forces an overdue pay increase, and providing free milk to children. The Indian Peoples Development Corporation and the Mapuche Vocational Institute were founded to address the needs of Chile's indigenous population. The nationalization of U.S. and other foreign-owned companies led to increased tensions with the United States. The Nixon administration brought international financial pressure to bear in order to restrict economic credit to Chile. Simultaneously, the CIA funded opposition media, politicians, and organizations, helping to accelerate a campaign of domestic destabilization. By 1972, the economic progress of Allende's first year had been reversed and the economy was in crisis. Political polarization increased, and large mobilizations of both pro- and anti-government groups became frequent, often leading to clashes. By early 1973, inflation was out of control. The crippled economy was further battered by prolonged and sometimes simultaneous strikes by physicians, teachers, students, truck owners, copper workers, and the small business class. A military coup overthrew Allende on September 11, 1973. As the armed forces bombarded the presidential palace (Palacio de La Moneda), Allende reportedly committed suicide. A military government, led by General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, took over control of the country. The first years of the regime were marked by serious human rights violations. On October 1973, at least 70 persons were murdered by the Caravan of Death. At least a thousand people were executed during the first six months of Pinochet in office, and at least two thousand more were killed during the next sixteen years, as reported by the Valech Report. Some 30,000 were forced to flee the country. A new Constitution was approved by a highly irregular and undemocratic plebiscite characterized by the absence of registration lists, on September 11, 1980, and General Pinochet became President of the Republic for an 8-year term. In the late 1980s, the regime gradually permitted greater freedom of assembly, speech, and association, to include trade union and limited political activity. The right-wing military government pursued decidedly laissez-faire economic policies. During its nearly 17 years in power, Chile moved away from economic statism toward a largely free market economy that saw an increase in domestic and foreign private investment, although the copper industry and other important mineral resources were not returned to foreign ownership. In a plebiscite on October 5, 1988, General Pinochet was denied a second 8-year term as president. Chileans elected a new president and the majority of members of a two-chamber congress on December 14, 1989. Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin, the candidate of a coalition of 16 political parties called the Concertación, received an absolute majority of votes. President Aylwin served from 1990 to 1994, that was considered a transition period. In December 1993, Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle, the son of previous president Eduardo Frei Montalva, led the Concertación coalition to victory with an absolute majority of votes. President Frei's administration was inaugurated in March 1994. During his government Chile's economy had their best years, although bad managing during last year plus the fact of the Asian crisis in 1998 got the country involved in a very bad situation affecting mainly to the middle class and to the small-Mid-Sized Companies. A presidential election was held on December 12, 1999, but none of the six candidates obtained a majority, which led to an unprecedented runoff election on January 16, 2000 between Ricardo Lagos and JoaquÃn LavÃn of the rightist Alliance for Chile. Ricardo Lagos Escobar of the Socialist Party led the Concertación coalition to a narrow victory, with 51.31% of the votes. He was sworn in March 11, 2000, for a 6-year term. The last period of president Frei due to the economy disaster led to a lower popularity for the Concertacion block. Bachelet, as President-elect, is visited by President Ricardo Lagos the day after the electionChile's current president-elect is the former health and later defense minister Michelle Bachelet, daughter of Alberto Bachelet, an air force general who was captured and tortured in the military coup of 1973 and died shortly after. Ms Bachelet continues the center-left Coalition of Parties for Democracy government in their fourth term. She is the first and so far the only woman president in the country's history. She won the 2006 runoff election against central-right-wing candidate Sebastián Piñera after none of the 4 main candidates obtained the necesary 50% of the votes in the first round of voting. The other candidates were previous Alliance for Chile right-wing candidate Joaquin Lavin and Tomas Hirsch, the far left candidate. Ms Bachelet will be sworn in for a 4-year term (one of the Constitution's reforms since old format was a 6 years period).

Certificate Vignette