Exchequer Bill of £100 (No. 322) lent to the South Sea Company issued on June 7, 1720. An exchequer bill is an interest bearing note issued by the British Treasury, first introduced in 1696 as a form as public borrowing. It could also be used in payment of taxes at its face value, and was to be redeemed at the Bank of England. This Bill is boldly signed by the Earl of Halifax. This item is over 289 years old.

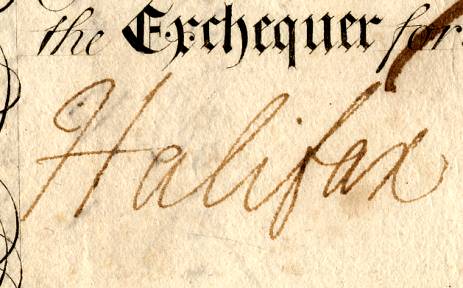

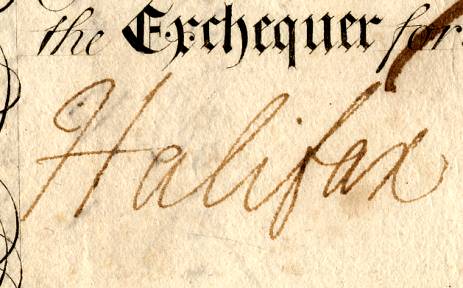

Bold Signature of Earl of Halifax

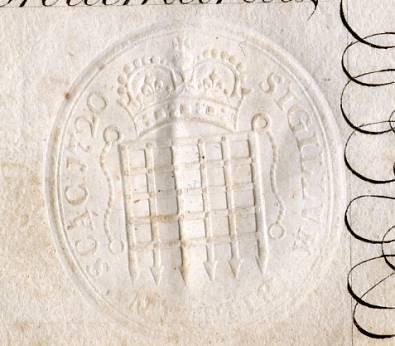

Seal embossed on Note A similar piece, No. 1704, is on display at the British Museum website as shown below: Exchequer Bill signed by the Earl of Halifax on display at the British Museum As you can see, the piece we offer here is in better condition than the one shown at the British Museum. According to the museum, these notes were used to inflate the South Sea Bubble. Interest-bearing Exchequer Bills were introduced in England in 1696 as a form of public borrowing: they were issued in return for money lent to the government. From the early eighteenth century the bills were accepted in payment of taxes, and could be redeemed at the Bank of England. Many carry several endorsements on the back, showing that they circulated among the public. This item was part of an issue to lend money to the infamous South Sea Company. Formed in 1711, the Company made fictitious claims to have a monopoly of trade with Spanish America. The unfounded promise of future wealth led to feverish speculation. Thousands of investors ploughed their fortunes into the Company, leading to a huge rise in the price of the Company's stock. However, the market collapsed and the bubble burst in September 1720, just a few months after this bill was issued. This certificate was signed by George Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax. George Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax PC (c.1684 9 May 1739), was a British politician. Halifax was the son of Edward Montagu, grandson of Henry Montagu, 1st Earl of Manchester, and Elizabeth Pelham. Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax, was his uncle. He sat as a Member of Parliament for Northampton between 1705 and 1715, when he succeeded his uncle as second Baron Halifax according to a special remainder. Only a few weeks after succeeding, he was created Viscount Sunbury and Earl of Halifax, revivals of the titles also held by his uncle. Two years later he was admitted to the Privy Council. Lord Halifax married, firstly, Ricarda Posthuma Saltonstale. After his first wife's death in 1711 he married, secondly, Lady Mary Lumley, daughter of Richard Lumley, 1st Earl of Scarborough. He died in 1739 and was succeeded in his titles by his son George. The family seat was Horton House, Horton, Northamptonshire. This house was demolished in 1936. South Sea Bubble The South Sea Bubble (1711 - September 1720) is the name given to the economic bubble which occurred due to overheated speculation in and subsequent disastrous collapse of the South Sea Company. The company was formed in 1711 by Robert Harley, and was granted exclusive trading rights in Spanish South America. The trading rights were pre-supposed on the successful conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession, which did not end until 1713, and the actual granted treaty rights were not as comprehensive as Harley had hoped. In return for the rights the company had taken on around £10 million of government bonds, exchanging them with the holders for stock in the company at 6% interest. The company did not undertake a trading voyage to South America until 1717 and made little actual profit, and when Spain and Britain returned to enmity in 1718 the short-term prospects of the company were very poor, but the company argued its longer-term future would be extremely profitable. In 1717 the company took on a further £2 million of public debt. In 1719 the company proposed a scheme by which it would take on the entire remaining national debt of Britain (£30,981,712), offering its own stock at 5% in exchange for government bonds in a deal lasting until 1727, the Bank of England proposed a similar deal. The company hoped to make a considerable profit and did much to advertise the proposal which was accepted in a slightly altered form in April, 1720. The company then set to talking up its stock with "the most extravagant rumours" of the value of its potental trade, and there was an enormous wave of "speculating frenzy". The share price had been rising from the time the scheme was proposed - from £128 in January 1720, to £175 in February, £330 in March and following the schemes acceptance to £550 at the end of May. A number of other joint-stock companies then joined the market, making usually fraudulent claims about other foreign ventures or bizarre schemes, they were nicknamed 'bubbles'. In June the Bubble Act required all joint-stock companies to have a Royal Charter. The grant of a charter to the South Sea was an added boost, its shares leapt to £890 in early June, this peak encouraged people to start to sell and the company directors ordered their agents to buy which propped the price up at around £750. The price finally reached £1,000 in early August and the level of selling was such that the price started to fall, triggering bankruptcies amongst those who had bought on credit and increased selling. The price fell slowly throughout August down to around £700. The attempts by the company directors to talk up the price failed and it continued to fall into September, the stockholders had lost confidence and a run started. By the end of September the stock had fallen to £150. The company failures now extended to banks and goldsmiths as they could not collect loans made on the stock, thousands of individuals were ruined (including many members of the aristocracy). With investors outraged Parliament was recalled in December and an investigation was begun. Reporting in 1721 it revealed widespread fraud among the company directors. Robert Walpole, who had argued against the scheme from the beginning, was forced to introduce a series of measures to restore public confidence.

Bold Signature of Earl of Halifax

Seal embossed on Note