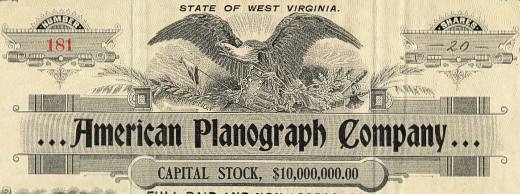

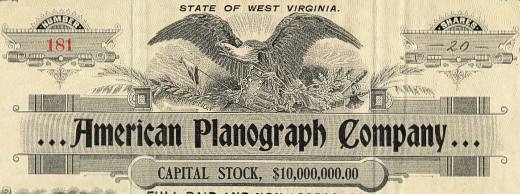

Beautiful stock certificate from the American Planograph Company issued in 1903. This historic document has an ornate border around it with a vignette of an eagle holding a shield and arrows. This item is hand signed by the Company's President (Chas. T. Moore) and Secretary and is over 112 years old.

Certificate Vignette Mergenthaler, Ottmar (11 May 1854-28 Oct. 1899), inventor of the Linotype hot-type composing machine, was born in Hachtel, Whrttemberg, in what is now Germany, the son of Johann Georg Mergenthaler, a schoolteacher, and Rosina Ackermann. As a boy growing up in Ensingen, he earned the nickname "Pfiffikusm@rle" (Cleverhead) because of his mechanical ability to start up the long-silent village clock. At age fourteen, after objecting to becoming a teacher in the family tradition, he was apprenticed for four years as a watch- and clock-maker to his stepmother's brother in Bietigheim. Because many soldiers were then returning from the Franco-Prussian War in 1872, Mergenthaler thought work prospects might be better in the United States. After landing in Baltimore, Maryland, he went directly to Washington, D.C., to work for August Hahl, son of his apprenticeship master, in a shop that designed and constructed clocks, bells, weather devices, and patent models. In 1874 Hahl and Mergenthaler moved to Baltimore, where business prospects seemed better. Mergenthaler, as shop foreman, in 1876 was first introduced to the problems of type composition when inventor Charles T. Moore brought in a typing machine designed to print characters in lithographic ink onto paper strips. The character impressions were to be mounted on a backing sheet and the words transferred to a lithographic stone for printing. Mergenthaler improved the reliability of the typing machine after Hahl had secured financial support from Moore's principal backer, James O. Clephane. A Washington, D.C., court reporter, Clephane had tested early models of Christopher Sholes's typewriters and had envisioned in Moore's invention a machine that would enable the speedy production of court reports and pamphlets. Continuing difficulties in transferring the lithographic images, however, led to abandonment of this process. In about 1878 Clephane proposed using a stereotypic process in which the typing machine would impress characters into papier-m>chJ strips. Mergenthaler now devised his rotary impression machine for which he received his first patent. The difficulties in successfully making metal castings from the strips, though, ended progress in this process. Mergenthaler, meanwhile, became Hahl's partner, and in 1881 he married Emma Lachenmayer, with whom he would have five children. Clephane, however, continued to experiment with possible composing processes. He supported Mergenthaler's plans to open his own shop in 1883 and backed the inventor's efforts to develop a new machine Mergenthaler had first suggested in 1879. Mergenthaler's first band machine used long, tapered metal bands with raised characters that made impressions of character lines in papier-m>chJ strips. Again, there were difficulties in making satisfactory castings. In 1884 he developed the second band machine; this device used bands of indented characters that were positioned in the machine so that actual lines of type could be cast from molten lead. This was Mergenthaler's first primitive Linotype. Confident of future success, Mergenthaler's backers, principally Clephane, formed the National Typographic Company with a capitalization of $1 million and named Mergenthaler as manager of its Baltimore factory. The company became the Mergenthaler Printing Company in 1885. Although the second band machine attracted wide attention, Mergenthaler nevertheless realized it would not produce type matching the quality of handset type and meeting the demands of a then-skeptical trade. He proposed another machine, one using matrices (molds) of single characters, and his backers reluctantly approved this new direction. The principle of single matrices that circulate in the machine has been used in all subsequent Linotypes. Mergenthaler's first commercial machine, the 1886 Blower, was named for the air blast used to propel the matrices. It was installed that summer at the New York Tribune to set newspaper type and a 500-page book, The Tribune Book of Open-Air Sports. Whitelaw Reid, Tribune publisher, headed a publishers' syndicate that envisioned the machine's money-making potential and provided additional capital through the Mergenthaler Printing Company. The stage was set in early 1888, though, for a confrontation between Reid and Mergenthaler. Reid, who is usually credited with naming the machine, and other syndicate members using the new devices complained that the machines were unreliable and unprofitable. Reid wanted a machine produced quickly; Mergenthaler wanted a perfect one. Because of this unresolved difference, Mergenthaler, then thirty-four, resigned under pressure as factory manager. Reid moved the factory that year to Brooklyn, New York, but disputes between Reid's New York stockholders and the Washington faction of Clephane and Lemon G. Hine led to Reid's ouster and Hine's selection as president. Mergenthaler, meanwhile, reestablished his own machine shop in Baltimore, developing an improved model built in both shops. The year 1891 marked the formation of the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, the return of control to the New York directors, the selection of Philip T. Dodge as the company's president, and Mergenthaler's perfection of the newer Model 1 Linotype. This machine overcame the objections of newspaper publishers. In 1895 the company reported that 2,608 machines were installed at 385 locations in almost every state or territory. Publishers at last found that the Linotype produced type much more quickly and at less cost than hand composition in addition to providing a "new dress [type] daily." The Linotype thus became the revolutionary advance over the hand process initiated by Johann Gutenberg in the 1450s. The early 1890s was a period when newspaper, book, and magazine printers tried out the new composing machines entering the market. Various contests and demonstrations were held, with the Linotype usually producing the best records. Organized labor initially had qualms about a machine that they feared would put its printers out of work, but by 1900 their objections had largely subsided as union printers had taken control of the machines and the demand for printed material had increased. Both before and after Mergenthaler's death, the Mergenthaler company defended its patents against interference and infringement by competing machines. It also bought out a competitor in 1895 to obtain patent rights for the crucial double-wedge spaceband used in justifying the lines of type. The Linotype thus "held the field" until after the inventor's principal patents expired and the competing Intertype was introduced in 1913. Linotypes were extensively improved over the years as installation proceeded in a majority of the nation's printing plants. The hot-type systems using them began their decline after World War II. Intense labor problems and the adoption of offset printing and cold-type photocomposition methods (and later computers) coincided with publishers' desires for lower costs. The Mergenthaler company ended U.S. production in 1971 after building nearly 90,000 Linotypes. Probably a few thousand were still in use in the United States in the early 1990s. History from Linotype Website.

Certificate Vignette