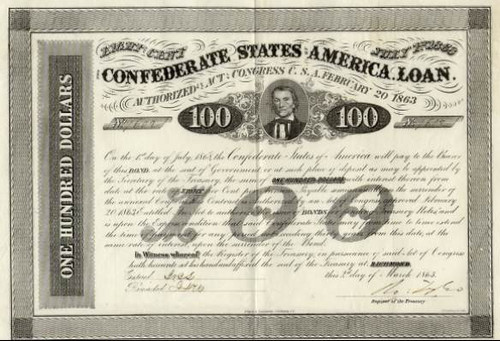

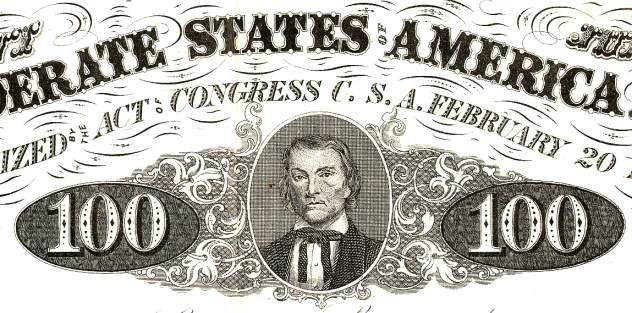

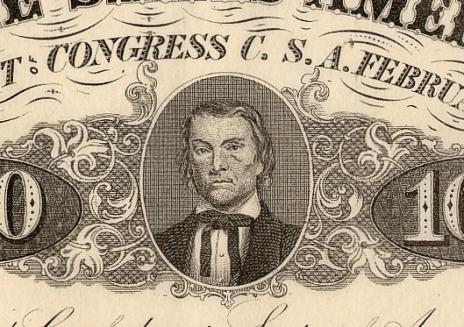

Beautifully printed certificate from the Confederate States of America dated March 2, 1863. This historic document was printed by Evans & Cogswell, Columbia, South Carolina and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of Alexander H. Stephens. The bond was issued under the Act of February 20, 1863. This certificate has been hand signed by the C. Rose. 7 coupons attached. Trimmed, otherwise EF+.

Certificate Vignette

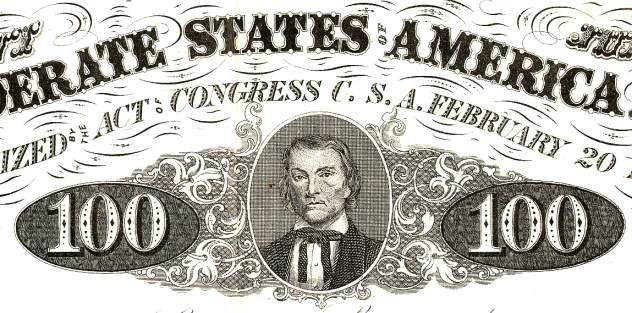

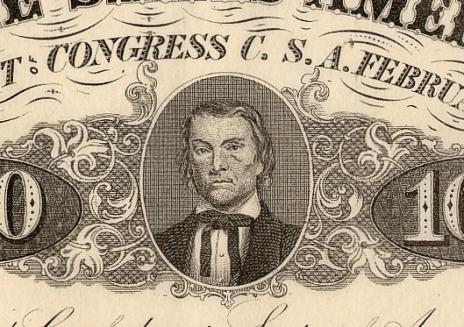

Certificate Vignette Alexander Hamilton Stephens (1812 -1883) Alexander Hamilton Stephens, LL. D., Vice-President of the Confederate States---a man eminent in natural abilities, in intellectual training, in statesmanship and moral virtues---grandson of a soldier under Washington--was one of that body of great men who stood firmly by the venture on independence made by the Southern people in 1861. He was born February 11, 1812, in Georgia, near Crawfordsville, where he is buried, and where a monument erected by the people speaks of his fame. Educated during his early youth in the schools of the times, he was graduated in 1832 at the age of twenty years, and was admitted to the bar in 1834. His practice of the profession scarcely opened before he was summoned to enter on the long and distinguished political career which gave his name an exceedingly prominent place in American history. After declining political honors and seeking to pursue without interruption a professional life, he was nevertheless forced by his constituency to represent them in political office. His county sent him in 1836 to the State legislature, repeated their selection until in 1841 he positively declined re-election. But in 1842 he was chosen State senator. His record as a State legislator shows him diligent in protecting all common interests, and in advancing the State's material welfare. His earliest course in public life at once foreshadowed that career in which he won the title of The Great Commoner. His first entry into the United States Congress occurred in 1843, after which he served 16 years with distinction constantly increasing until in 1859 he returned to private life by his own choice, with premature congratulations in an address to his constituents on account of what he supposed at that time a full settlement of all dangerous questions. He had been a firm advocate of the compromise measures of 1850, and having subsequently participated in the settlement of the Kansas troubles, accepted the result as an end of sectional strife so far as the South was concerned. The presidential campaign of 1860 found him an advocate of the election of Stephen A. Douglas, in which he led the electoral ticket for that statesman in Georgia. The election of Mr. Lincoln alarmed him as being a disturbance of the settlement and a menace to the Union, but with ardent devotion to the republic of States under the Constitution, he endeavored to avert secession, proposing' to fight the Republican administration inside the Union, and failing there to invoke concerted separation of all the Southern States. He was elected a member of the Georgia convention of 1861, and after strenuous effort to delay the passage of an ordinance of separate State secession, he yielded when the act was passed and gave his entire energies to maintain the Confederacy. His objections were to the expediency of immediate secession and not to the right of his State to secede. The convention wisely chose him as a delegate to the Provisional Congress which had been appointed to assemble at Montgomery, by which body he was unanimously chosen Vice-President of the Confederate States, an office which constituted him the President of the Confederate Senate. His talents and commanding influence throughout the South caused his services to be put to immediate use, not only in assisting in the organization of the Confederate government, but in the general effort to induce all Southern States to join those which had already seceded. On this account he was commissioned to treat with Virginia on behalf of the Confederacy and succeeded in gaining that valuable State before its ordinance of secession had been formally ratified by the people. In the formation of the Confederate Constitution his statesmanship and profound acquaintance with the principles of government were found to be of great value. That great instrument was an improvement, in his opinion, on the Constitution of the United States, receiving his warm commendation although some features which he had urged were not adopted. He says of the supreme charter of the new republic, "The whole document utterly negatives the idea which so many have been active in endeavoring to put in the enduring form of history, that the convention at Montgomery was nothing but a set of 'conspirators' whose object was the overthrow of the principles of the Constitution of the United States, and the erection of a great ' slave oligarchy' instead of the free institutions thereby secured and guaranteed. This work of the Montgomery convention, with that of the Constitution for a provisional government, will ever remain not only as a monument of the wisdom, foresight and statesmanship of the men who constituted it, but an everlasting refutation of the charges which have been brought against them." Mr. Stephens fully approved the peace policy proposed by the Confederate government, which was manifested by sending commissioners to Washington without delay Astounded by the treatment these eminent gentlemen received, he vigorously denounced the duplicity of Mr. Seward while declaring his opinion that Mr. Lincoln had been persuaded to change his original policy The attempt to reinforce Sumter, in the light of the deception practiced on the commissioners, was pronounced by him "atrocious" and "more than a declaration of war. It was an act of war itself." From the outset Mr. Stephens favored a vigorous prosecution of all diplomatic measures, and an active military preparation by the Confederacy. He and Mr. Davis were in happy accord as to the general purpose of the Confederacy so tersely expressed by the Confederate President on the reassembling of Congress in April, 1861, "We seek no conquest, no aggrandizement, no concessions from the free States. All we ask is to be let alone--that none shall attempt our subjugations by arms. This we will and must resist to the direst extremity. The moment this pretention is abandoned the sword will drop from our hands, and we shall be ready to enter into treaties of amity and commerce mutually beneficial." As the war progressed the Vice-President was often called upon to make addresses to the people at critical periods, in all of which he characterized the invasion of the South as an unjust war for conquest and subjugation, "the responsibilities for all its sacrifices of blood and treasure resting on the Washington administration." Frankly declaring that the slavery institution as it existed at the start had its origin in European and American cupidity, and was not an unmitigated evil, he justified the Confederacy in protecting that species of property against the assaults of a majority, but did not declare it to be the" corner stone" of the new Republic, as is often quoted against him. He held that slavery as a domestic institution under the control of the States was attacked by those who sought to establish the rule that the Federal government had the power to regulate any domestic institution of any State. His views regarding the political relations of the Federal and State governments were nearly allied to those of Jefferson, and these views he carried with him in his construction of the Confederate constitution. Believing that lib. erty depended more on law than arms--for he was by nature a civilian, and by learning a jurist--he could not agree with others in all war measures adopted at Richmond. Mr. Lincoln's administration was arraigned by him with great severity, because of its utter disregard of all constitutional restraint. So also he objected to any breach of the constitution by his own government. His opposition to the financial policy, the conscription, the suspension of the habeas corpus, and to other war measures, was very decided, and differences occurred between the Vice-President and the Confederate administration; but his friendly intercourse With President Davis and the Cabinet remained to the close of the war. He says, "these differences, however wide and thorough as they were, caused no personal breach between us," a statement which Mr. Davis confirms. It is proper to mention that Mr. Stephens was the defender of President Davis against all malicious attacks as long as he lived. The cruel and vicious charges against Mr. Davis concerning the treatment of prisoners were promptly condemned by him as one of "the boldest and baldest attempted outrages upon the truths of history which has ever been essayed; not less so than the infamous attempt to fix upon him and other high officials on the Confederate side the guilt of Mr. Lincoln's assassination. Mr. Stephens very certainly entertained the idea from the earliest days of secession that a process of disintegration of the old union could occur by the pursuit of a proper policy, and that eventually as he says, "a reorganization of its constituent elements and a new assimilation upon the basis of a new constitution" would result in a more perfect union of the whole. These views met with little favor. Their accomplishment was too distant, too uncertain, too impracticable to suit the times. He was willing at all times to make peace and restore the Union on the basis of the constitution adopted at Montgomery, or simply on the sincere recognition of the absolute sovereignty of the States. But neither of these was admissible as a basis of reunion. As the war went on and Confederate resources diminished to the point of exhaustion, Mr. Stephens began to press with some vehemence upon the administration at Richmond his views as to measures designed to end the carnage of battle. The latter years of the conflict were in the main attended with disasters under which the people of the South were bearing up with stout heart, occasionally relieved by victories on the field and rumors of attempts by a Northern peace party to suspend hostilities. Mr. Stephens was among the foremost in the peace movement, but without the least degree manifesting any want of fealty to the Confederacy. It was thought that he and Mr. Lincoln--two old and attached friends who held each other in great regard--could they get together and talk over the question confidentially, a basis for peace would be found. The political status at the North in the summer of 1863 seemed to favor an attempt to approach the United States government on the subject as well as to effect an arrangement for resumption of exchange of prisoners of war. Under these circumstances Mr. Stephens proposed to go in person to Washington and hold a preliminary interview with Mr. Lincoln" that might lead eventually to successful results." But while this proposition was under discussion the Confederate armies crossed the Potomac and threatened Washington, producing a state of feeling in the cabinet of Mr. Lincoln which seemed to Mr. Stephens to be unfavorable to any negotiations. He was, however, commissioned by Mr. Davis to make the effort to secure exchanges of prisoners, and did so with the result of a prompt refusal by the Federal authorities to receive any commissioner on that subject. Mr. Stephens thought in 1864 that the reaction against Mr. Lincoln's war policy was on account of the fear that the so-called war power would become as dangerous to the liberties of the Northern States, and he entertained the opinion that a proper encouragement given to the peace people 'throughout the North would result in their political success in the elections of that year, and thus bring into power at Washington a body of men who would treat with the South. "It was our true policy," he writes, "while struggling for our own independence, to use every possible means of impressing upon the minds of the real friends of liberty at the North the truth that if we should be overpowered and put under the heel of centralism that the same fate would await them sooner or later." On this line he sympathized with the resolutions passed in March, 1864, by the legislature of Georgia, evidently prepared to strengthen the opposition at the North to the administration of Mr. Lincoln. But the overwhelming re-election of Mr. Lincoln dissipated the hope of adjustment. The final effort at negotiation was made through Mr. Stephens and his associate commissioners, Campbell and Hunter, appointed by Mr. Davis, who met Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward at Hampton Roads February 3, 1865, in informal and futile conference. Mr. Stephens was chief spokesman in that famous interview, and has given his recollections very fully of all that occurred. He pressed Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward to consent to an armistice with the view of arranging a demand by the United States upon the French emperor Maximilian to release Mexico from European control in accordance with the popular "Monroe doctrine." This diversion, he believed, would open the way to a restoration of the Union. Mr. Seward replied that the suggestion was only a "philosophical theory," and Mr. Lincoln said that the disbanding of all armies and the installation of Federal authority everywhere was absolutely the preliminary to any cessation of hostilities. Failing in this effort to secure an armistice, Mr. Stephens and the other commissioners requested a statement of conditions upon which the war might end. Would the seceded States be at once related as they were before to the other States under the Constitution? What would be done with the property in slaves? What would be the course of the United States toward the actors in secession? Questions of this character, but not in these precise words, were answered by saying that all armed resistance must cease and the government be trusted to do what it thought best. There appears no evidence that Mr. Lincoln wrote the word "Union" on a paper and said that Mr. Stephens could write under it what he would, and there is no probability that anything so silly, impotent and unwise was done by the sagacious President of the United States. There was no promise of payment for slave property, but only a suggestion by Mr. Lincoln that he himself would favor it, although his views in that regard were well known to be entirely inutile. Thus the conference failed as to any beneficial result. Mr. Stephens considered the Southern cause hopeless after returning from the Hampton Roads conference, and finding the administration resolved on defending Richmond to the last, he left Richmond for his home February 9th, without any ill-humor with Mr. Davis or any purpose to oppose the policy adopted by the cabinet, and remained in retirement until his arrest on the 11th of May. He was confined as a prisoner for five months at Fort Warren, which he endured with fortitude and without yielding up his convictions. His release by parole occurred in October, 1865, and on the following February the Georgia legislature elected him United States senator, but Congress was now treating Georgia as a State out of the Union, in subversion of the Presidential proclamation of restoration and he was therefore refused a seat. Later, when the reconstruction era was happily ended, he was elected representative to Congress, in which he took his seat and served with unimpaired ability. In the year 1882 he was elected governor of Georgia, and during his term was taken sick at Savannah, where he died March 4, 1883. Extraordinary funeral honors were paid him at the capital and in the State generally, and his memory is cherished warmly as one of the great men of his times. (Source: The Confederate Military History)

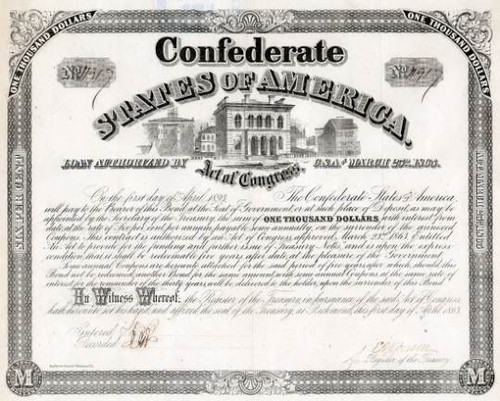

Certificate Vignette

Certificate Vignette