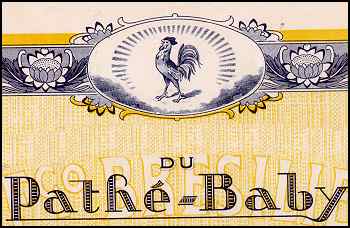

Beautifully engraved Certificate from the famous Pathe Baby Company issued in 1923. This historic document has an ornate border around it with a vignette of the famous Pathe Singing Rooster. This item is hand signed and is over 80 years old. There are several rows of unused coupons attached to the bottom of the certificate.

Certificate Vignette The Pathe Companies were a major supplier of Nicklodeon products and was a large producer of movies especially comedies. The made many types of phonographs and movie projector equipment. Moving pictures, using film, were invented towards the end of the nineteenth century. Although there are rival claims as to who was first, moving picture shows were soon well established, and the commercial cinema began to assume an important role in peoples' lives. Early movie cameras were hand-cranked and cumbersome. They were also expensive, too expensive for all but the most wealthy families. Manufacturers were quick to see that there was a potential market for equipment designed for the amateur, which would be less expensive to buy and run. One of the first attempts to reduce the cost was a German 35 mm. device which combined the camera and projector in one body. Another idea was to reduce film costs; the Birt Acres Birtac camera was one of several which used 17.5 mm. film, half the width of 35 mm. This device was produced in 1899, and again the camera could be converted to a projector. The outfit cost 10 guineas, a lot of money in 1899. These two cameras were followed by many others; one called the Biokam, also accepting 17.5 mm. film, offered a still picture release, so that still pictures could be taken with the camera as well as cine films. Not all cameras took 17.5 mm. or 35 mm. film; the Kammatograph took circular glass plates, taking 600 pictures on a twelve inch disc. The Kinora took pictures which could be assembled into reels like those used in seaside pier machines. By loading a reel into a viewer, the pages would be flipped over, giving the impression of movement. Film at this time was dangerous; early 17.5 mm. and 35 mm. film is on an unstable nitrate base which is extremely inflammable. It was not until around 1912 that cellulose-based "safety" film was available, and even then it was not universally supplied. Early "safety" film usually has the word 'safety' in the film margin. Home movies were beginning to be accepted. For many families, the cost of making their own films was too high, but they could afford to buy or hire films and watch them at home. In a pre-television era, this was exciting. Edison's Home Kinetoscope and Pathe's Home Cinematograph both had the same target audience: people who were not necessarily interested in making films, but who wanted to watch commercially made films at home. Film libraries boomed, just as home video rental outlets grew rapidly in the early nineteen eighties. None of these early film systems have survived as amateur gauges, although 35 mm. is very popular for still photography and is still used for most professional movies. The first popular amateur gauge was introduced by Pathe in 1922 and it is still used by enthusiasts today. 9.5 mm. film has the sprocket hole down the centre of the film, placed between the frames. In addition, some films have notched titles; this means that, to save film, a title frame would be held in position for the audience to read, rather than repeating the title over about 160 frames (to give 10 seconds reading time). These commercially printed films were contained in small cassettes; the system was called the Pathe Baby. The following year, Eastman Kodak brought out 16 mm., another surviving gauge, although now more popular among professionals than amateurs. They made the Cine-Kodak camera and the Kodascope projector for their new gauge; Pathe brought out the Baby camera for their 9.5 mm. film by the end of the year. Meanwhile, other companies had produced cameras and projectors for 16 mm., notably Bell & Howell, whose Filmo was the first clockwork 16 mm. camera. Kodak brought out their clockwork Cine-Kodak Model B in 1925; this camera sold very well. It was still obvious to the companies that their best hope of large profits was to extend their potential market, and this could best be done by reducing the cost, especially the cost of film. This led to the introduction of what is now known as Standard-8 film: 16 mm. film which is run through the camera twice, exposing half of the film each time. After processing, the film is split and joined to make one length, 8 mm. wide. In 1932 Kodak announced the new film, and the Cine Kodak Eight camera. Bell & Howell followed suit in 1935, with the Filmo Straight Eight, in which the film was only 8 mm. wide and run through the camera once. These were the first boom years for amateur film, both for viewing commercially produced films and for making home movies. Technical innovation continued; the Eumig C-2 of 1935 was one of the first cameras to have a built in light meter; the Eumig C-4 had electric drive. Cassette loading cameras made it easier to load the film into the camera. By the early 1930s, sound could be provided by disc systems which synchronised with the projector, but a sound-on-film system for amateur use had been demonstrated in 1931. This British system did not achieve general acceptance however; it was the American system which did that, demonstrated in 1932 by RCA-Victor. By 1933 there was a choice of sound projectors for the 16 mm. home movie viewer and in 1934 Pathe brought out a 9.5 mm. sound projector. Colour film was made available for the amateur in the nineteen thirties, with several different systems for both 16 mm. and 9.5 mm. by 1935. Kodachrome colour film was made available in 1936. All of this development effort was financed by the boom in home cinematography, even though the equipment and film costs were too high for all but the relatively wealthy. It was cut short by the outbreak of war in 1939. After the war, it was apparent that the huge improvements in film had made the smaller gauges much more attractive for the amateur. 9.5 mm. survived, helped by a loyal home-market in France, but 8 mm. was the popular amateur gauge, with 16 mm. for the more serious amateur film-maker. Technical innovation continued, but the next, and last, really major innovation was in 1965, when Kodak launched Super 8. This is an easy-load cartridge system which runs through the camera once. It made filming easy for everyone, and cheap plastic cameras were made in large numbers for the snap-shooter who wished to take some films on holiday. Fuji brought out their 8 mm. cassette loading system, Single 8, in the same year. All three 8 mm. gauges still survive, although they are used by enthusiasts now, the mass market having defected to video.

Certificate Vignette