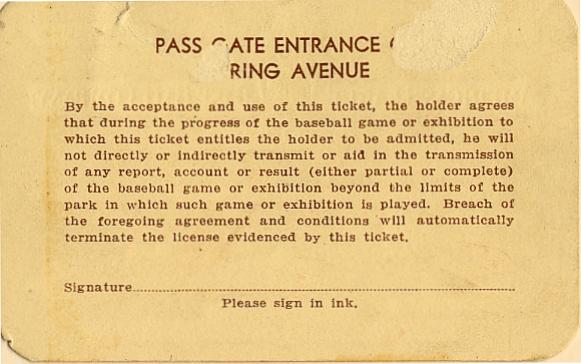

Historic Baseball pass from the American League Base Ball Company of St. Louis issued in 1939. This item has the printed signature of the Company's President, Donald Barnes and is over 68 years old. The pass was issed to M. W. Heath.

Back side of pass The Baltimore Orioles were originally the St. Louis Browns before the franchise was transferred to Baltimore in 1954. Both St. Louis and Baltimore boasted rich traditions in major league baseball during the final decades of the 1800s. The Baltimore Orioles of the 1890s was one of the era's most notorious and celebrated teams, both for its roughhouse ways and adherence to "scientific baseball," which emphasized the use of guile in playing the game. St. Louis originally fielded a team called the Brown Stockings, initially in the National Association, which folded after a single season, then for two seasons in the National League, which was established in 1876. The St. Louis club then joined a rival major league, the American Association, where it won several championships before returning to the National League, along with the Baltimore Orioles, as part of a merger in 1891. The Browns were owned by controversial beer baron Chris Von Der Ahe, who fell out of favor with his fellow owners; St. Louis was stripped of its franchise in 1899. After three years without major league baseball, the city would land an American League franchise three years later. The American League was originally a minor league, the Western League, that changed its name and declared it was the equal to the National League, launching its first major league season in 1901. Baltimore was awarded an American League franchise and the new incarnation of the Orioles played two seasons before the franchise moved to New York City, where the club was renamed the Highlanders and eventually became known as the New York Yankees and emerged as one of the most successful sports franchises in the world. As a result of the Oriole's defection, Baltimore would be without major league baseball for the next half century. St. Louis, on the other hand, would land a National League club, via the 1999 transfer of the Cleveland Spiders, as well as one from the new American League. Following the 1901 season, the Milwaukee Brewers franchise of the fledgling American League was bought for $35,000 by 33-year-old Robert Lee Hedges, who moved the club to St. Louis, renaming it the Browns. He cleaned up Sportsman's Park where the club played and the Browns over the next dozen years drew well and were profitable. Another rival major league, the Federal League, was formed in 1913, and after completing two seasons it agreed to disband. As part of the settlement with Major League Baseball, Hedges sold the Browns to one of the owners of the St. Louis Terriers, Philip Ball, for $525,000. Hedges made a tidy profit on his investment in the team, becoming the last owner of the Browns to make money on the club. He also held the distinction of giving Branch Rickey his start as a baseball executive, naming him the Browns' manager. Rickey would one day revolutionize baseball by refining the minor league farm system of developing big league talent while with the St. Louis Cardinals, and by breaking down baseball's racial barriers when with the Brooklyn Dodgers by signing Jackie Robinson, the first African-America to play major league baseball in the modern era. The Brown's new owner was a hard-drinking, gruff ex-ballplayer, as well as erstwhile cowhand and construction worker, who made a fortune manufacturing ice machines. Rickey, a teetotaler, campaigned for a national prohibition of alcohol and was promptly shown the door by Ball. It was only the first of many mistakes Ball would make while running the Browns. In 1920 he allowed the National League's Cardinals to share Sportsmen Park, which permitted his local competitor to sell its own park and invest the money in Branch Rickey's farm system. As a result, the Cardinals went on to win several World Series while the Browns became a perennial loser; St. Louis went from being a "Brown's town," to a city that adored the Cardinals. Ball even paid to increase the seating capacity of Sportsman Park, a move that did little to help the Browns, whose attendance declined steadily, but proved a windfall for the immensely popular Cardinals. When Ball died in 1933 the club drew just 88,113 fans for the entire year. One game that season attracted just 34 paying customers. It was no wonder that nobody wanted to buy the team. The executor of Ball's estate finally turned to Rickey, who recruited Bill DeWitt, Sr., the Cardinals team treasurer, and Donald Barnes, president of American Investment Company, to buy the Browns for $325,000. Barnes put up $50,000, DeWitt $25,000, and the club raised another $200,000 by selling stock at $5 a share. Under new ownership the Browns fared no better on the field or the box office, so that by 1941 Barnes sought permission from the American League to relocate the franchise to Los Angeles. The meeting was held on December 8, 1941, one day after the attack on Pearl Harbor that precipitated the United States' entry into World War II. Because of the sudden uncertainty in the world, Barnes was turned down, but the war did lead to the greatest moment in the Brown's history. In 1944, when the level of major league talent was severely diluted because so many players were serving in the military or alternative service, the Browns were able to win its only American League pennant. Even this moment of glory, however, failed to help the club improve its image in St. Louis. The Browns had the misfortune of meeting the Cardinals in the World Series, losing to their tenants in six games. Control of the Browns changed hands once again in 1945 when board member Richard Muckerman, along with Bill and Charlie DeWitt, took over the running of the club. The team continued to draw poorly, prompting Muckerman in 1945 to sign and play Pete Gray, a one-armed outfielder, as a gate attraction. The move only succeeded in solidifying the Browns' reputation as baseball's pathetic country cousin. Because the team drew poorly during the postwar years, it had to sell off what little talent it possessed to stay afloat, resulting in teams that even fewer fans wanted to pay to watch. In 1951, Bill Veeck, the former owner of the Cleveland Indians and renowned maverick, bought the Browns with the ambitious goal of driving the Cardinals out of town. The Cardinal's owner was enduring some income tax difficulties, but Veeck's hopes were dashed when millionaire brewer August Busch bought the rival club. Veeck's best known moment while running the Browns came just one month into his tenure, when he had a midget named Eddie Gaedel brought into a game to pinch hit--after jumping out of a cake. With such a compact strike zone, less than two inches after assuming a crouch, Gaedel walked. The next day, the American League banned Gaedel and announced that all future player contracts had to be approved by the league office. Veeck tried others stunts, such as Grandstand Manager's Night, when the fans were able to vote on the starting pitcher and strategic decisions by using placards that said "Yes" on one side and "No" on the other. Source: International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 66. St. James Press

Back side of pass