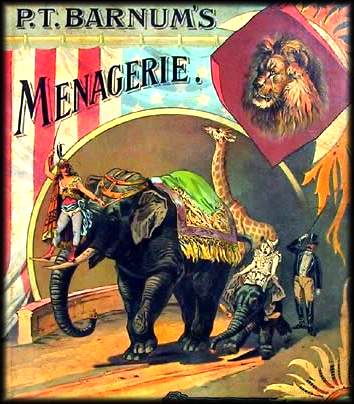

Beautifully engraved RARE certificate from the Barnum and Van Amburgh Museum and Menagerie Company issued in 1867. 50 shs. State arms. Printed in a light gold which has blended in with the aging of the paper. Boldly signed by P.T. Barnum as president. A rare and perhaps unique, historic circus certificate. Minor edge split, VF.* had all year. Secretary ( O. J. Fergurson ). The certificate #16 was issued to Hyatt Frost for 50 shares at $100 each.

P. T. Barnum 1810 - 1891 BARNUM, Phineas Taylor, exhibitor, born in Bethel, Connecticut, 5 July 1810. His father was an innkeeper and country merchant, who died in 1825, leaving no property, and from the age of thirteen to eighteen the son was in business in various places, part of the time in Brooklyn and New York city. Having accumulated a little money, he returned to Bethel and opened a small store. Here he was very successful, especially after taking the agency for a year of a lottery chartered by the state for building the Groton Monument, opposite New London. When the lottery charter expired, he built a larger store in Bethel, but through bad debts the enterprise proved a failure. After his marriage in 1829 he established and edited a weekly newspaper entitled "The Herald of Freedora," and for the free expression of his opinions he was imprisoned sixty days for libel. When Barnum was fifteen his father died, making the young man the sole provider for his family. By the age of eighteen, Barnum had opened his own fruit store and organized a lottery distribution agency. At nineteen he married Charity Hallot, a member of the congregation of his church. He also started his own newspaper, called the Herald of Freedom and Gospel Witness. By now, Barnum was financially stable, but being the outspoken person he was, he found it hard to stay out of trouble. In 1831, he attacked a Protestant minister in his paper, for which he spent sixty days in jail. The publicity in the case made him well known. He went into jail an unknown newspaper owner and came out a hero and a martyr. This taught him another valuable lesson -- that there is no such thing as bad publicity. In 1834 he moved to New York, his property having become much reduced. He soon afterward visited Philadelphia, and saw there oil exhibition a colored slave woman named Joyce Heth, advertised as the nurse of George Washington, one hundred and sixty-one years old. Her owner exhibited an ancient-looking, time-colored bill of sale, dated 1727. Mr. Barnum bought her for $1,000, advertised her extensively, and his receipts soon reached $1,500 a week. Within a year Joyce Heth died, and a post-mortem examination proved that the Virginia planter had added about eighty years to her age. Having thus acquired a taste for the show business, Mr. Barnum traveled through the south with small shows, which were generally unsuccessful. In 1841, although without a dollar of his own, he purchased Scudder's American Museum, named it Barnum's Museum, and, by adding novel curiosities and advertising freely, he was able to pay for it the first year, and in 1848 he had added to it two other extensive collections, besides several minor ones. In 1842 he first heard of Charles S. Stratton, of Bridgeport, Connecticut, then less than two feet high and weighing only sixteen pounds, who soon became known to the world, under Mr. Barnum's direction, as General Tom Thumb, and was exhibited in the United States and Europe with great success. In 1849 Mr. Barnum, after long negotiations, engaged Jenny Lind to sing in America for 150 nights at $1,000 a night, and a concert company was formed to support her. Only ninety-five concerts were given ; but the gross receipts of the tour in nine months of 1850 and 1851 were $712,161, upon which Mr. Barnum made a large profit. In 1855, after being connected with many enterprises besides those named, he retired to an oriental villa in Bridgeport, which he had built in 1846. He expended large sums in improving that City, built up the city of East Bridgeport, made miles of streets, and therein planted thousands of trees. He encouraged manufacturers to remove to his new City, which has since been united with Bridgeport. But in 1856-'7, to encourage a large manufacturing company to remove there, he became so impressed with confidence in their wealth and certain success that he endorsed their notes for nearly $1,000,000. The company went into bankruptcy, wiping out Mr. Barnum's property; but he had settled a fortune upon his wife. He went to England again with Tom Thumb, and lectured with success in London and other English cities, returning in 1857. His earnings and his wife's assistance enabled him to emerge from his financial misfortunes, and he once more took charge of the old museum on the corner of Broadway and Ann street, and conducted it with success till it was burned on 13 July 1865. In 1868, tragedy struck again. After just a year in the circus business, on March 2, Barnum watched the Barnum and Van Amburgh Museum and Menagerie burn down once more, this time with all the circus animals in it. In 1871 Barnum came out of retirement to improve his circus. He built tents big enough for 10,000 people. Since this meant that not everybody would be able to see the circus ring clearly, he opened three rings instead of one. This was the birth of the three-ring circus. It was a stroke of genius. Thousands and thousands of people came to see his circus, including high-ranking politicians. In 1872 Barnum first called his circus the "Greatest Show on Earth," and it is called so even today. In 1873, Barnum's wife Charity, who had been ill for some time, died. The following year, Barnum married Nancy Fish, an Englishwoman who was forty years younger than he. Two years later, he became the mayor of Bridgeport. The time he spent in office was the greatest era in the history of Bridgeport because he spent so much money and energy developing the city. By the time his term ended, Bridgeport was well known throughout the United States and even the world. He was involved in every aspect of the everyday life of the city. In particular, he spent a lot of his energy improving the steamboat industry since Bridgeport was already an important hub of transportation. In 1883 Barnum went to England to buy an enormous elephant called "Jumbo" for his circus. The elephant was a great attraction in his circus, and Barnum loved the animal; but a year later, Jumbo was struck and killed by a freight train. Barnum again retired from the circus. Years later, Barnum had retired to Bridgeport, Connecticut politics, on the remaining profits of his famous American Museum in New York, and his astounding promotion of such financial successes as Joice Heth, "George Washington's 161 year old nurse," Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, Tom Thumb, the Feejee Mermaid, and an assortment of bearded ladies and side-show attractions. In the intervening years, he had been involved in at least one behind-the-scenes partnership with his old friend Seth Howes. Barnum and Howes financed the acquisition and showing of the first genine herd of elephants in America back in 1851.11 However, that tour had no ring acts; it wasn't officially even called a "circus," and Barnum didn't travel with the show. Still, by 1871, his name was one of the best known in America, and his success at drawing crowds had earned him the title, the "Shakespeare of Advertising." He had made and lost several fortunes; his museum had burned down twice; and Barnum, now past sixty years old, was fully prepared to enjoy his retirement years in leisure. However, two successful Wisconsin circus owners, William C. Coup and Dan Castello, succeeded in luring him back into the circus business in a big way. They convinced Barnum to join them in framing a new enterprise with the profitable but unwieldy title, the "P. T. Barnum Museum, Menagerie and Circus, International Zoological Garden, Polytechnic Institute and Hippodrome." In 1890 Barnum suffered a stroke and was confined to bed at home in his beloved Bridgeport. Knowing that death was imminent, he was curious to know what people would say about him once he was dead. When the New York Sun heard about this, it published an early obituary so that his wish could be fulfilled. Two weeks later, on April 7, 1891, P. T. Barnum said goodbye to his life of struggles and triumphs, a life in which he always stood up to the challenge and emerged victorious.

Letters Between P. T. Barnum and Henry Bergh of the ASPCA After Barnum's American Museum burned in 1865, he opened a new museum and menagerie several blocks to the north. Shortly after the founding of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1866, its President, Henry Bergh, responded to complaints that staff fed live rabbits to boa constrictors in the new museum as a source of entertainment. The following letters reveal the growing tensions between Bergh and Barnum. The New York World published the Bergh and Barnum letters on March 19, 1867, commenting that "the snake controversy is funny as well as instructive." As Barnum's final letter to the Evening Post makes clear, other publications took up the issue in order to poke fun at Bergh. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Letter from Henry Bergh (ASPCA) to the Managers of Barnum's Museum: December 11, 1866 Gentlemen: I some time since called at Barnum's Museum for the purpose of protesting against the cruel mode of feeding the snake which is there on exhibition. The gentleman, whom I spoke with, who informed me that he was acting for Mr. Barnum in his absence, expressed his willingness to use his influence to have the evil corrected. Nothing, it seems has been done in that direction, as I am this moment informed by a gentleman who was present some four weeks ago, that he witnessed the feeding of the animal, along with other spectators, and pronounced the scene cruel and demoralizing in the extreme; several live animals having been thrown into its cage, to be slowly devoured! I boast of no finer sensibilities than other men, but, I assert, without fear of contradiction, that any person who can commit an atrocity such as the one I complain of, is semi-barbarian in his instincts. It is with a view to prevent and punish such offences, that this society has been created and laws enacted. It may be urged that these reptiles will not eat dead food--in reply to this I have to say, then let them starve--for, it is contrary to the merciful providence of God that wrong should be committed in order to accomplish a supposed right. But, I am satisfied that this assertion is false in theory and practice, for no living creature will allow itself to perish of hunger, with food before it, be the aliment dead or alive. I therefore, am led to the conclusion that this cruel deed, is a part of the spectacle; in total disregard of the demoralizing effects of it, or the inhumanity, which results therefrom. I have therefore, respectfully to apprize you that, on the next occurrence of this cruel exhibition, this Society will take legal measures to punish the perpetrators of it. Please let me hear from you without delay. Your obedient servant, Henry Bergh, President Letter from P. T. Barnum to Henry Bergh: New York, March 4th, 1867 Henry Bergh, Esq. Dear Sir: On my return from the West in December last, I found your letter of December 11th, addressed to this association, threatening us with punishment if we permitted our Boa Constrictors to eat their food alive. You furthermore declared, that our assertion that these reptiles would die, unless permitted to eat their food alive, was "false in theory and practice, for no living creature will allow itself to perish with hunger, with food before it, be the ailment dead or alive." I enclose a letter from Professor Agassiz, denying your statement. In addition to threatening us with prosecution you take it upon yourself to denounce us as "semi-barbarians," simply because we choose to conduct our business in the only way which we believe will be satisfactory to that public, who expect to see animals here as nearly in their natural state as they can be exhibited. I, sir, was much rejoiced at the establishment of your society, and believe it can do a world of good in saving dumb animals from abuse, but in the present instance you are unquestionably in the wrong, and I give you notice that this establishment will continue to feed all its animals in accordance with the laws of nature. If upon reflection, you think proper to write us a letter for publication, stating that since reading Professor Agassiz's letter to us, you withdraw your objections, that will satisfy us. Otherwise we shall feel compelled to self-defence to publish your former letter in connection with that from Professor Agassiz. Truly yours, P. T. Burnum President of Barnum's and Van Amburgh's Museum and Menagerie Letter to P. T. Barnum from Louis Agassiz, enclosed in above letter to Bergh: Cambridge, February 28, 1867 P. T. Barnum, Esq., New York Dear Sir: On my return to Cambridge I received your letter of the 15th of January. I do not know of any way to induce snakes to eat their food otherwise than in their natural manner: that is alive. Your Museum is intended to show to the public the animals, as nearly as possible, in their natural state. The society of which you speak is, I understand, for the prevention of unnecessary cruelty to animals. It is a most praiseworthy object, but I do not think the most active member of the society would object to eating lobster salad because the lobster was boiled alive, or refuse roasted oysters because they were cooked alive, or raw oysters because they must be swallowed alive. I am, dear sir, your obedient servant, L. E. Agassiz Letter to P. T. Barnum from Henry Bergh: New York, March 7, 1967 P. T. Barnum, Esq., New York Dear Sir: I hereby acknowledge the receipt of a letter from you on the date of the 4th of March, including one to you from Professor Agassiz, relating to the feeding of your boa-constrictor on live animals. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty of Animals was chartered by the Legislature of this State for the purpose indicated by its title. Among the vast number of complaints made to it, imploring its interposition in behalf of suffering brute creature, was one received from a gentleman whose name is purposely withheld but whose entire communication is at any time subject to your inspections, the salient point of which I quote below. In describing what he had witnessed at your place of amusement, he says: "A rabbit was thrust into the cage of a serpent, when it immediately rushed to the furthest corner, and commenced trembling like an aspen leaf. After some time the boa slowly brought its head so as to bring its eyes to bear upon its victim, and then rested. The intense terror of the poor rabbit, and its pitiable helplessness made me sick. I implored the keeper to take it out, but was laughed at for my pains. It was in the evening when the rabbit was put into the cage. I thought of it all night. The next morning I called to see if my little friend was out of its misery. The situation was unchanged. The reptile had not moved a particle. Its eyes still rested upon the rabbit, which was closely crouched in the same corner and trembling violently. In the evening I called again; still the same and the next morning still the same. At length, late in the evening of the third day, I called, and the little rabbit had seemingly fallen into a semi-stupor, from which it would arouse and open its eyes, but close them again after the manner of a man who sleeps and nods in his chair. The serpent had moved his head a few inches nearer. When I called the next morning the little rabbit was gone. The above occurrence took place in the public exhibition room, and was part of the show. If Yankee ingenuity cannot devise some other means of keeping these horrible creatures alive, I am sure we are better without the sight of them." On the receipt of this letter, I called at your place of business, and on my representation of the case was assured by the gentlemen in charge -- who appeared to be humanely inclined -- that the practice should be discontinued but subsequently, a second letter having been received by me, announcing a repetition of the cruel performance, I wrote you the note referred to, in reply to which a letter was sent me by your agent again deprecating the proceeding, and strongly asserting that it shall not be repeated. Thus the matter rested until the receipt of your letter of the 4th, transmitting a threat to give my letter to the public unless "upon reflection I thought proper to write you, stating that since reading Professor Agassiz's letter to you, I withdrew my objections, etc. etc. In reply to this I have to say that the hastily written note to which you refer was not intended for publication, but if you think any business capital can be realized from it, I have no objection to its sharing the fate of everything subjected to the ordeal of your fertile genius. But I may perhaps, be permitted at the same time to express the surprise I feel that so consummate an adept in the school of humbug as your self published autobiography proves you to be should make the mistake of believing that the same public, after reading that delectable volume, would fail to see through the transparent covering with which the motive is enveloped. This, however, is your affair, not mine. As to withdrawal of my objection, after reading Professor Agassiz's letter, I have to say that so far from discovering by the perusal of it any reason for changing my long cherished opinions of the necessity of practicing humanity to the brute creation, I am more convinced than ever of the necessity of laboring still more assiduously in that cause, in order to counteract the unhappy influence which the expressions of that justly distinguished savant is calculated to occasion. Permit me to add that I scarcely know which emotion is paramount in my mind, regret or astonishment, that so eminent a philosopher should have seemingly cast the weight of his commanding authority into the scale where cruelty points the index in its favor. The result is obvious, therefore; the offensive letter must be published, although I predict beforehand that so doing will occasion no convulsion of nature nor otherwise disturb the repose of society, nor will it even realize for its exhibition the results anticipated; but it is possible, on the contrary, that it may cause parents and other guardians of the morals of the rising generation to discontinue conducting them to a mis-called museum, where the amusement chiefly consists in contemplating the prolonged torture of innocent, unresisting, dumb creatures. Your obedient servant, Henry Bergh Letter from P.T. Barnum to Henry Bergh: New York, March 11, 1867 Henry Bergh, Esquire President of American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Sir: On my return from Connecticut, for but a few hours sojourn in the city, I find your letter of the 7th. It is lamentable that a gentleman standing at the head of an institution which, if properly conducted, would command the respect and sympathy of all well disposed persons, should be so incredulous and possess such a superficial knowledge of the subject as to be deceived by so silly and absurd a letter as you quote from. This entire story of the trembling, fearful rabbit is a shallow hoax. And the pretence that during four dark nights and three days this persistent, unwinking snake should be staring incessantly at his terrified little victim, is simply a ridiculous Munchausenism, founded upon the old story of serpent charming birds. But no naturalist will pretend for a moment, that the lazy, dull-eyed boa constrictor possesses any such power, or that any bird or animal placed in his cage has the slightest instinctive admonition that he is in danger. On the contrary, pigeons jump about upon him as carelessly as if they were on the ground, and roost upon his back all night as fearlessly as if he was the branch of a tree. Rabbits lie and sleep among his folds with as much unconcern as if within their own burrows. This whole story, therefore, of those long days and nights of terror, and the gradual wearing out of the sleepless rabbit, reducing him to a "semi stupor like a man who sleeps and nods on his chair," is as ludicrous a piece of fiction as ever was read in the "Arabian Nights Tales," and its publication will inevitably make you the laughing stock of every naturalist in Christendom. Twenty-five years ago I witnessed the eventful workings in London of an institution of the same title as that of which you are president, and I have frequently urged the importance of organizing a similar society here. But sir, discretion, civility, and good judgment are requisite in securing to the objects of that institution the best results. Letters "hastily written," charging a man with being a "semi-barbarian" and haughtily threatening him with punishment for doing what no man with a well-balanced mind could imagine he had done, are not in my humble judgment, the most effective means for a person in your position to make use of. Your last letter, which seems not to have been so "hastily written," but evidently intended for the public press, in as uncharitable as it is unjust. When you attribute to me a desire to make "business capital" out of a transaction originated by yourself, wherein you have unwarrantably applied to me insulting epithets, and treated me in a most ungentlemanly manner, simply because I wished to be set right on a point wherein you have clearly attempted to place me in the wrong, is not worthy of a person filling the honorable and responsible position to which you, sir, have been elected. Your vulgar allusions to "hum" and that "delectable volume" betray low breeding and a surplus of self-conceit which will but tend to deepen the impression which many sensible and humane men have formed in regard to your unfitness for the office of "President of the American Society, etc." Your abrupt charges and sweeping insinuations are offensive and without reason. For instance, your assertion that the letter of Professor Agassiz confirms you still more in the opinion of "the necessity of practicing humanity to the brute creation," from which the public are to infer that the learned and honorable Professor did not so zealously believe and practice on that belief as you do. Herein seems to be one of your greatest foibles. You apparently consider everybody "brutal" and "barbarous," and opposed to "practicing humanity," unless they agree with you in the attempt to set at defiance the laws of nature. Your dictatorial air is unsufferable, and your concluding threat that the publication of your former letter in connection with that of Professor Agassiz will drive children and their mothers away from a museum in which I have but a partial pecuniary interest, and for the financial returns of which I don't care a "tuppence" so that the public get, as usual, four times more genuine instruction and innocent amusement than they pay for, is a specimen of petty malice which will accords with the general tenor of your conduct in your new position. And then, again, your offensive and unwarrantable charges of the "insults anticipated" by me in such publication, emanates only from the brain of a man mounted upon stilts, who seems to be delighted in seeing himself in print in whatever shape circumstances may place him there. When private enterprise has invested half a million of dollars, and incurs a yearly disbursement of $300,000 in which to place before the public a full representation of every department of natural history for a mere nominal sum--and enterprise never before attempted in any city in the world without governmental aid--it simply is disgraceful for you to assert that the "amusement chiefly consists in contemplating the prolonged torture of innocent and unresisting dumb creatures." How weak must a person feel his position to be when he attempts to fortify it by such thoughtless and absurd statements, and how little does he appreciate the true dignity of his office when he thus descends to miserable pettyfogging and the unjust imputation of bad motives to those who take quite as humane and much more rational view of the subject than himself. The officers of your institution, sir, are gentlemen of too much worth and command too generally the respect of the community for its president to degrade it and them by "hasty" unreflecting, and unjust deportment toward others. In attempting to prevent the abuse of beasts your influence will not be increased by your abuse of men. As you seem to court the pillory by asking for the publication of your last letter, I bow to your request, wondering at you temerity, but thinking to use your own language, "It is your affair, not mine." Of course no public officer like yourself has a right to consider his official orders as "private" and exempt from publication. The public all have an interest in the proper management of a society for the prevention of cruelty to animals, and have a right to know whether its chief officer is fit for his position. Your arbitrary conduct, however, compelled my associates to send their reptiles to a neighboring state to be fed; but we shall have no more such tom-foolery until driven to it by that legal decision which you threaten and to which we most willingly appeal. Your obedient servant, P. T. Barnum Letter from Barnum to the Evening Post: American Museum, June 22, 1867 To the Editors of the Evening Post: Your paper of yesterday gives a remedy, proposed by the London Punch, to meet the objection of the president of "The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals" to feeding serpents in the only manner which nature permits. Mr. Punch may overcome English sensitiveness by rejecting live rabbits as food for the boas constrictor, and substituting "Welsh rabbits" in their places. But Shakespeare tells us of "maggot ostentation," and from my experience with the tender susceptibilities of Mr. Bergh, I tremble lest the keen scent of that gentleman might enable him to smell danger to animal suffering by that process, and that he would, therefore, offer a small mite of objection even to feeding serpents upon toasted cheese! Truly yours, P. T. Barnum History from University of Bridgeport.

Letters Between P. T. Barnum and Henry Bergh of the ASPCA After Barnum's American Museum burned in 1865, he opened a new museum and menagerie several blocks to the north. Shortly after the founding of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1866, its President, Henry Bergh, responded to complaints that staff fed live rabbits to boa constrictors in the new museum as a source of entertainment. The following letters reveal the growing tensions between Bergh and Barnum. The New York World published the Bergh and Barnum letters on March 19, 1867, commenting that "the snake controversy is funny as well as instructive." As Barnum's final letter to the Evening Post makes clear, other publications took up the issue in order to poke fun at Bergh. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Letter from Henry Bergh (ASPCA) to the Managers of Barnum's Museum: December 11, 1866 Gentlemen: I some time since called at Barnum's Museum for the purpose of protesting against the cruel mode of feeding the snake which is there on exhibition. The gentleman, whom I spoke with, who informed me that he was acting for Mr. Barnum in his absence, expressed his willingness to use his influence to have the evil corrected. Nothing, it seems has been done in that direction, as I am this moment informed by a gentleman who was present some four weeks ago, that he witnessed the feeding of the animal, along with other spectators, and pronounced the scene cruel and demoralizing in the extreme; several live animals having been thrown into its cage, to be slowly devoured! I boast of no finer sensibilities than other men, but, I assert, without fear of contradiction, that any person who can commit an atrocity such as the one I complain of, is semi-barbarian in his instincts. It is with a view to prevent and punish such offences, that this society has been created and laws enacted. It may be urged that these reptiles will not eat dead food--in reply to this I have to say, then let them starve--for, it is contrary to the merciful providence of God that wrong should be committed in order to accomplish a supposed right. But, I am satisfied that this assertion is false in theory and practice, for no living creature will allow itself to perish of hunger, with food before it, be the aliment dead or alive. I therefore, am led to the conclusion that this cruel deed, is a part of the spectacle; in total disregard of the demoralizing effects of it, or the inhumanity, which results therefrom. I have therefore, respectfully to apprize you that, on the next occurrence of this cruel exhibition, this Society will take legal measures to punish the perpetrators of it. Please let me hear from you without delay. Your obedient servant, Henry Bergh, President Letter from P. T. Barnum to Henry Bergh: New York, March 4th, 1867 Henry Bergh, Esq. Dear Sir: On my return from the West in December last, I found your letter of December 11th, addressed to this association, threatening us with punishment if we permitted our Boa Constrictors to eat their food alive. You furthermore declared, that our assertion that these reptiles would die, unless permitted to eat their food alive, was "false in theory and practice, for no living creature will allow itself to perish with hunger, with food before it, be the ailment dead or alive." I enclose a letter from Professor Agassiz, denying your statement. In addition to threatening us with prosecution you take it upon yourself to denounce us as "semi-barbarians," simply because we choose to conduct our business in the only way which we believe will be satisfactory to that public, who expect to see animals here as nearly in their natural state as they can be exhibited. I, sir, was much rejoiced at the establishment of your society, and believe it can do a world of good in saving dumb animals from abuse, but in the present instance you are unquestionably in the wrong, and I give you notice that this establishment will continue to feed all its animals in accordance with the laws of nature. If upon reflection, you think proper to write us a letter for publication, stating that since reading Professor Agassiz's letter to us, you withdraw your objections, that will satisfy us. Otherwise we shall feel compelled to self-defence to publish your former letter in connection with that from Professor Agassiz. Truly yours, P. T. Burnum President of Barnum's and Van Amburgh's Museum and Menagerie Letter to P. T. Barnum from Louis Agassiz, enclosed in above letter to Bergh: Cambridge, February 28, 1867 P. T. Barnum, Esq., New York Dear Sir: On my return to Cambridge I received your letter of the 15th of January. I do not know of any way to induce snakes to eat their food otherwise than in their natural manner: that is alive. Your Museum is intended to show to the public the animals, as nearly as possible, in their natural state. The society of which you speak is, I understand, for the prevention of unnecessary cruelty to animals. It is a most praiseworthy object, but I do not think the most active member of the society would object to eating lobster salad because the lobster was boiled alive, or refuse roasted oysters because they were cooked alive, or raw oysters because they must be swallowed alive. I am, dear sir, your obedient servant, L. E. Agassiz Letter to P. T. Barnum from Henry Bergh: New York, March 7, 1967 P. T. Barnum, Esq., New York Dear Sir: I hereby acknowledge the receipt of a letter from you on the date of the 4th of March, including one to you from Professor Agassiz, relating to the feeding of your boa-constrictor on live animals. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty of Animals was chartered by the Legislature of this State for the purpose indicated by its title. Among the vast number of complaints made to it, imploring its interposition in behalf of suffering brute creature, was one received from a gentleman whose name is purposely withheld but whose entire communication is at any time subject to your inspections, the salient point of which I quote below. In describing what he had witnessed at your place of amusement, he says: "A rabbit was thrust into the cage of a serpent, when it immediately rushed to the furthest corner, and commenced trembling like an aspen leaf. After some time the boa slowly brought its head so as to bring its eyes to bear upon its victim, and then rested. The intense terror of the poor rabbit, and its pitiable helplessness made me sick. I implored the keeper to take it out, but was laughed at for my pains. It was in the evening when the rabbit was put into the cage. I thought of it all night. The next morning I called to see if my little friend was out of its misery. The situation was unchanged. The reptile had not moved a particle. Its eyes still rested upon the rabbit, which was closely crouched in the same corner and trembling violently. In the evening I called again; still the same and the next morning still the same. At length, late in the evening of the third day, I called, and the little rabbit had seemingly fallen into a semi-stupor, from which it would arouse and open its eyes, but close them again after the manner of a man who sleeps and nods in his chair. The serpent had moved his head a few inches nearer. When I called the next morning the little rabbit was gone. The above occurrence took place in the public exhibition room, and was part of the show. If Yankee ingenuity cannot devise some other means of keeping these horrible creatures alive, I am sure we are better without the sight of them." On the receipt of this letter, I called at your place of business, and on my representation of the case was assured by the gentlemen in charge -- who appeared to be humanely inclined -- that the practice should be discontinued but subsequently, a second letter having been received by me, announcing a repetition of the cruel performance, I wrote you the note referred to, in reply to which a letter was sent me by your agent again deprecating the proceeding, and strongly asserting that it shall not be repeated. Thus the matter rested until the receipt of your letter of the 4th, transmitting a threat to give my letter to the public unless "upon reflection I thought proper to write you, stating that since reading Professor Agassiz's letter to you, I withdrew my objections, etc. etc. In reply to this I have to say that the hastily written note to which you refer was not intended for publication, but if you think any business capital can be realized from it, I have no objection to its sharing the fate of everything subjected to the ordeal of your fertile genius. But I may perhaps, be permitted at the same time to express the surprise I feel that so consummate an adept in the school of humbug as your self published autobiography proves you to be should make the mistake of believing that the same public, after reading that delectable volume, would fail to see through the transparent covering with which the motive is enveloped. This, however, is your affair, not mine. As to withdrawal of my objection, after reading Professor Agassiz's letter, I have to say that so far from discovering by the perusal of it any reason for changing my long cherished opinions of the necessity of practicing humanity to the brute creation, I am more convinced than ever of the necessity of laboring still more assiduously in that cause, in order to counteract the unhappy influence which the expressions of that justly distinguished savant is calculated to occasion. Permit me to add that I scarcely know which emotion is paramount in my mind, regret or astonishment, that so eminent a philosopher should have seemingly cast the weight of his commanding authority into the scale where cruelty points the index in its favor. The result is obvious, therefore; the offensive letter must be published, although I predict beforehand that so doing will occasion no convulsion of nature nor otherwise disturb the repose of society, nor will it even realize for its exhibition the results anticipated; but it is possible, on the contrary, that it may cause parents and other guardians of the morals of the rising generation to discontinue conducting them to a mis-called museum, where the amusement chiefly consists in contemplating the prolonged torture of innocent, unresisting, dumb creatures. Your obedient servant, Henry Bergh Letter from P.T. Barnum to Henry Bergh: New York, March 11, 1867 Henry Bergh, Esquire President of American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Sir: On my return from Connecticut, for but a few hours sojourn in the city, I find your letter of the 7th. It is lamentable that a gentleman standing at the head of an institution which, if properly conducted, would command the respect and sympathy of all well disposed persons, should be so incredulous and possess such a superficial knowledge of the subject as to be deceived by so silly and absurd a letter as you quote from. This entire story of the trembling, fearful rabbit is a shallow hoax. And the pretence that during four dark nights and three days this persistent, unwinking snake should be staring incessantly at his terrified little victim, is simply a ridiculous Munchausenism, founded upon the old story of serpent charming birds. But no naturalist will pretend for a moment, that the lazy, dull-eyed boa constrictor possesses any such power, or that any bird or animal placed in his cage has the slightest instinctive admonition that he is in danger. On the contrary, pigeons jump about upon him as carelessly as if they were on the ground, and roost upon his back all night as fearlessly as if he was the branch of a tree. Rabbits lie and sleep among his folds with as much unconcern as if within their own burrows. This whole story, therefore, of those long days and nights of terror, and the gradual wearing out of the sleepless rabbit, reducing him to a "semi stupor like a man who sleeps and nods on his chair," is as ludicrous a piece of fiction as ever was read in the "Arabian Nights Tales," and its publication will inevitably make you the laughing stock of every naturalist in Christendom. Twenty-five years ago I witnessed the eventful workings in London of an institution of the same title as that of which you are president, and I have frequently urged the importance of organizing a similar society here. But sir, discretion, civility, and good judgment are requisite in securing to the objects of that institution the best results. Letters "hastily written," charging a man with being a "semi-barbarian" and haughtily threatening him with punishment for doing what no man with a well-balanced mind could imagine he had done, are not in my humble judgment, the most effective means for a person in your position to make use of. Your last letter, which seems not to have been so "hastily written," but evidently intended for the public press, in as uncharitable as it is unjust. When you attribute to me a desire to make "business capital" out of a transaction originated by yourself, wherein you have unwarrantably applied to me insulting epithets, and treated me in a most ungentlemanly manner, simply because I wished to be set right on a point wherein you have clearly attempted to place me in the wrong, is not worthy of a person filling the honorable and responsible position to which you, sir, have been elected. Your vulgar allusions to "hum" and that "delectable volume" betray low breeding and a surplus of self-conceit which will but tend to deepen the impression which many sensible and humane men have formed in regard to your unfitness for the office of "President of the American Society, etc." Your abrupt charges and sweeping insinuations are offensive and without reason. For instance, your assertion that the letter of Professor Agassiz confirms you still more in the opinion of "the necessity of practicing humanity to the brute creation," from which the public are to infer that the learned and honorable Professor did not so zealously believe and practice on that belief as you do. Herein seems to be one of your greatest foibles. You apparently consider everybody "brutal" and "barbarous," and opposed to "practicing humanity," unless they agree with you in the attempt to set at defiance the laws of nature. Your dictatorial air is unsufferable, and your concluding threat that the publication of your former letter in connection with that of Professor Agassiz will drive children and their mothers away from a museum in which I have but a partial pecuniary interest, and for the financial returns of which I don't care a "tuppence" so that the public get, as usual, four times more genuine instruction and innocent amusement than they pay for, is a specimen of petty malice which will accords with the general tenor of your conduct in your new position. And then, again, your offensive and unwarrantable charges of the "insults anticipated" by me in such publication, emanates only from the brain of a man mounted upon stilts, who seems to be delighted in seeing himself in print in whatever shape circumstances may place him there. When private enterprise has invested half a million of dollars, and incurs a yearly disbursement of $300,000 in which to place before the public a full representation of every department of natural history for a mere nominal sum--and enterprise never before attempted in any city in the world without governmental aid--it simply is disgraceful for you to assert that the "amusement chiefly consists in contemplating the prolonged torture of innocent and unresisting dumb creatures." How weak must a person feel his position to be when he attempts to fortify it by such thoughtless and absurd statements, and how little does he appreciate the true dignity of his office when he thus descends to miserable pettyfogging and the unjust imputation of bad motives to those who take quite as humane and much more rational view of the subject than himself. The officers of your institution, sir, are gentlemen of too much worth and command too generally the respect of the community for its president to degrade it and them by "hasty" unreflecting, and unjust deportment toward others. In attempting to prevent the abuse of beasts your influence will not be increased by your abuse of men. As you seem to court the pillory by asking for the publication of your last letter, I bow to your request, wondering at you temerity, but thinking to use your own language, "It is your affair, not mine." Of course no public officer like yourself has a right to consider his official orders as "private" and exempt from publication. The public all have an interest in the proper management of a society for the prevention of cruelty to animals, and have a right to know whether its chief officer is fit for his position. Your arbitrary conduct, however, compelled my associates to send their reptiles to a neighboring state to be fed; but we shall have no more such tom-foolery until driven to it by that legal decision which you threaten and to which we most willingly appeal. Your obedient servant, P. T. Barnum Letter from Barnum to the Evening Post: American Museum, June 22, 1867 To the Editors of the Evening Post: Your paper of yesterday gives a remedy, proposed by the London Punch, to meet the objection of the president of "The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals" to feeding serpents in the only manner which nature permits. Mr. Punch may overcome English sensitiveness by rejecting live rabbits as food for the boas constrictor, and substituting "Welsh rabbits" in their places. But Shakespeare tells us of "maggot ostentation," and from my experience with the tender susceptibilities of Mr. Bergh, I tremble lest the keen scent of that gentleman might enable him to smell danger to animal suffering by that process, and that he would, therefore, offer a small mite of objection even to feeding serpents upon toasted cheese! Truly yours, P. T. Barnum History from University of Bridgeport.