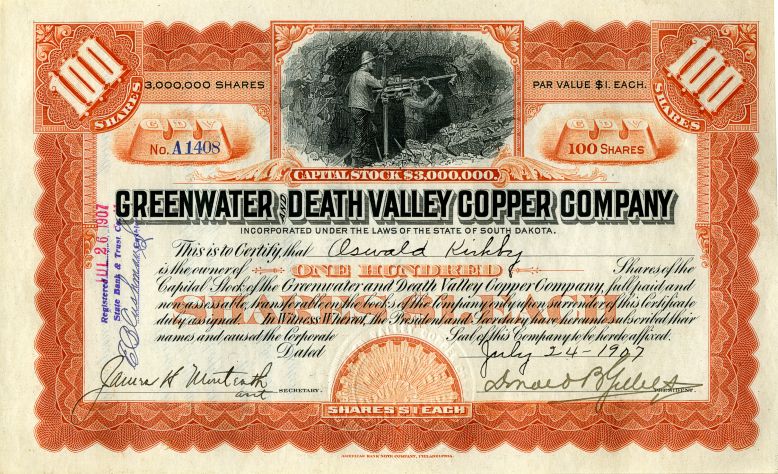

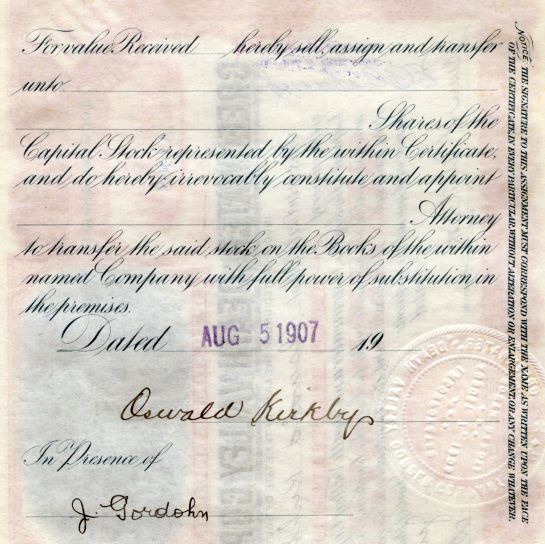

Beautifully engraved uncancelled certificate from the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company issued in 1907. This historic document was printed by the American Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of men working in a mine. This item is hand signed by the Company's V. President, Donald B. Gillies and Asst. Secretary and is over 111 years old. The certificate was issued to Oswald Kirby and is endorsed by him on the verso. The certificate has not been folded and is in EF condition.

Certificate

Back of Certificate United States Investor, Volume 17, Part 2, Issues 27-52 - 1907 The Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company was organized under the laws of South Dakota with an authorized capital of 3,000,000 shares, par $1, 1,000,000 shares being set aside as treasury stock. The proposition is controlled by interests identified with Charles M. Schwab, the officers and directors being as follows: President, Frank Keith, superintendent and manager of Tonopah Mining Co.'s interests; vice-president, Donald B. Gillies, president Tonopah Extension Mining Co., and general manager of Charles M. Schwab's mining interests; treasurer, Charles K. Knox, president Montana-Tonopah Mining Co.; Malcolm L. Macdonald, J. Ross Clark, M. R. Ward, T. L. Oddie and C. B. Zabriskle. The property consists of 20 claims in the Greenwater camp, about 70 miles south of Bullfrog, Nev., and just across the line in Inyo county, Cal. This properly does not adjoin the Nevada Smelting & Mines Corporation holdings, but is near the mines of the Furnace Creek Copper Co., Greenwater Extension, United Greenwater, Greenwater Syndicate, etc. The stock is probably selling as high as, or higher than, present conditions warrant, but it is believed that the further opening up of the mine will bring to light the existence of substantial ore bodies giving good values, and consequently the shares are likely to go higher in time. The main ledge is said to traverse the property in a bold outcrop some 4,800 feet long, in addition to which there are at least two other well-defined veins. On the largest vein system three shafts are being sunk, the deepest being around the 100-foot level. About September 1 250,000 shares of its treasury stock were offered for public subscription at $1 per share. Since that time it has sold in the open market as high as $3.75 per share.

History from the National Park Service During the short and spectacular Greenwater boom, fully seventy-three mining companies were incorporated within the district, and literally scores of smaller mines and prospects were opened Papers have been located for thirty-three of the companies which did incorporate, which show their combined capitalization value to be over $76,000,000. Although the exact capitalization totals of the other forty incorporated companies cannot be determined, the minimum standard capitalization for the time period was $1,000,000 per company, which would give us a total capitalization value of the Greenwater district mines of over $116,000,000. This total, of course, in no way reflects the actual amount of money spent in the district, but it does give some idea of the amazingly vast amounts which investors and promoters hoped to reap from the rich copper ores of Greenwater. The Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company consisted of sixteen claims and five fractions. The development workstarted with three shafts, one on the east end, one at the center and one at the west end of the property. The deepest working is on the Copper Queen claim, consisting of a shaft, down 70 feet. The veins on the different properties vary in width from fifteen to forty feet. Greenwater Death and Valley Copper Company A major mine in the Greenwater district, the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company, which was owned and operated by one of the great business magnates of the early twentieth century, Charles Schwab. After making his fortune in steel, Schwab had been attracted to the gold fields of Nevada following the Tonopah and Goldfield booms, and, as we have seen, dabbled constantly in mines in and around the Bullfrog area. When the Greenwater rush began, Schwab, like most major operators in the area, rushed to the site in order to capitalize on what seemed to be the biggest boom of them all. Schwabs activities are hard to follow during the early days of the boom, since he had several agents in and around the mining towns of Death Valley who bought and sold mining properties on his behalf. For a short time in early 1906, Schwab held an interest in the Funeral Range Copper Company, but it was shortly sold, apparently because he was unable to gain outright control of the company. In July of 1906, Schwab began buying up mining claims in his own right. Schwab paid $180,000 to Arthur Kunze and his partners for a group of sixteen claims, and on August 10, 1906, the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was incorporated. The capitalization was for $3,000,000, one of the largest capitalizations in the district, and Schwab retained majority control of the company, even though his name does not appear as a member of the board of directors. The company by this time held title to 300 acres of ground, and announced that the installation of mining machinery and the inauguration of an extensive development campaign would soon start. In addition to its mineral holdings in Greenwater, the Schwab company also owned water rights at Ash Meadows, and preliminary plans were announced to install a pumping and power station in that vicinity. Lumber and supplies began to flow into the company's property at Greenwater and work began. According to the usual procedure a limited amount of Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company stock was offered for sale in Rhyolite and other mining towns of the west, and by the end of August, the main shaft of the mine was down to 100 feet in depth, and work was started on two other shafts. The company ordered three gas hoists to facilitate the sinking. With the organization of a company such as this, with a man of Schwab's reputation behind it, the local newspapers immediately began to follow the progress of the company. The Bullfrog Miner reported in late September that the company was already employing forty miners on its property. In addition, it said, the company had ordered three gas hoists (of 25, 40 and 50-horsepower), which would easily give it the largest hoisting capacity in the district. These first indications of development work were quite promising, and the Inyo Independent reported towards the end of September that the company had "good ore. Although the Furnace Creek Copper Company was the darling stock of the Greenwater District, Greenwater Death Valley Copper did not do poorly. The attraction of the Schwab name--even though he had never attempted copper mining before--plus the good location and the obvious intent of the company to develop its property extensively, caused the price of its stock to soar upwards, until it was selling for $2 per share in late September, twice its par value. By the end of that month, the three new hoists had arrived at the mine and were being placed above their shafts, two of which were already below the 100-toot level. The company added a few more claims to its property list in early October, and spurred by this and other mysterious activities, the newspapers soon picked up the smell of something big. Since the biggest thing they could imagine would be a combination of Clark's and Schwab's mines--the two largest in the district--incessant rumors circulated of a merger between the two powerful operators. The rumors caused especially heavy trading of the stocks of both companies in Boston and New York, and the rumors became so proliferant that the papers began to believe themselves. The Inyo Independent reported in mid-October that the merger between the companies was practically final, since the main points affecting it had been settled between Clark and Schwab. When another month passed, however, without any merger announcements, the Bullfrog Miner revised its estimate and reported that difficulties had arisen, which had delayed the consolidation. In the meantime, the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was working hard, and early in November began taking shipping ore out of one of its shafts. By this time the company had two of its shafts below 100 feet, a third below 50 feet, and had built two comfortable frame offices on its property. Work continued through the rest of 1906, and by early December the two deeper shafts were at the 200-level, and the Greenwater Death Valley Copper company had emerged as one of the largest operations in the district. Then, on December 15th, the long-anticipated merger took place. Unfortunately, the papers had been speculating about the wrong companies, however, for the Furnace Creek Copper Company had no part in the merger. Instead, a consolidation was announced, of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper, the United Greenwater Copper and several unincorporated mines owned by John Brock and some Philadelphia financiers. The new merger company was named the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines and Smelting Company, and had a capitalization of $25,000,000, with five million shares worth $5 each. It was easily the largest incorporation that the Death Valley region had ever seen. The new company was a holding corporation, and as such bought up the controlling interests in the companies it took over. The stock distribution in the new company was based upon the amount of stock which had been sold in the older companies, and 68 percent of the merger company's stock went to buy out the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, 18 percent to the United Greenwater, and the rest to the owners of the unincorporated mines. Charles Schwab, it was definitely pointed out, was in control of the holding company, and plans were announced for the erection of a smelter at Ash Meadows, where the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company already had water rights. In addition, the holding company announced that it would build a railroad from the smelter site to the Greenwater mines. A smelting expert was hired for $25,000 per year to supervise the selection of the construction site and the construction of the plant, and hopes were raised that the smelter would be running within a year. Under the management arrangement of the holding company, however, the subsidiary companies under its control would continue to work on their own, retaining their names, identities and management--subject, of course, to the approval of Schwab and the parent company. Thus the mines continued to explore and develop their own deposits, and the holding company was used for a pooling of resources and capital, which would be necessary in order to finance the capital expenditures which were proposed. [15] Copper Queen shaft Illustration 216. an early view of the Copper Queen shaft of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, ca. December 1906. This was the shaft which was ultimately sunk to the depth of over 1400 feet. In this view, however, work has barely startd, and the miners are still using a crude hand whim to raise the rock to the surface. The young town of Kunze may be seen in the background. Photo courtesy Nevada Historical Society. Copper Queen shaft Illustration 217. Another view of the same shaft, this one taken below ground, where an intermediate hand whim was being used. The man sitting at the right, with suspenders, notebook and pen in pocket, is undoubtedly the mine superintendent. He may also be seen in the background in the preceeding picture. Photo courtesy Nevada Historical Society. Under the impetus of the new merger arrangements, and with the Greenwater boom at its very peak, the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company opened 1907 in impressive style, increasing its work force to nearly fifty men! Two more gas hoists were added to the property, bringing the total to five hoists pumping away over five separate shafts. Four of the shafts were over 100 feet in depth, and the deepest one had reached 125 feet. By early February the holding company announced that construction plans were completed for its smelter, which would cost $1,500,000 to build, and reaffirmed that a rail line would be constructed between the smelter site and the mines. The Death Valley Chuck-Walla reported that the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company had itself spent over $100,000 since starting work in August of 1906, and now had all five shafts down past the 100-foot point. Labor costs alone were running the company $10,000 a month to pursue its vigorous campaign. The deepest shaft was now down to 140 feet, and an air compressor had been ordered to force air down to the men working below ground. Early in March the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company added more mines to its holdings, including those of the Greenwater El Capitan Copper company. Construction on the smelter was slated to start within sixty days, and survey work for the railroad spur was started. By the middle of that month, the deepest shaft on the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company's property was near the 300-foot level, and two others were down to 275 and 200 feet. Three shifts were working around the clock, a machine shop had been installed at the central shaft, an assay office was built, and a sawmill was under construction, to facilitate the shaping of timbers for the deep mine shafts. The rapid exploitation of the company's property continued through April, and the payroll was increased to 75 men. By the 19th of that month the deepest shaft was down 475 feet, and had fairly good copper ore (3%) at the bottom. Sinking kept pace in the other shafts, and towards the end of April, four of the company's five working shafts were below 40:0 feet. As May progressed, crosscuts were run from several of the shafts, as exploratory measures, and by the end of May another small strike was reported at the 485-foot level in one of the shafts. In the meantime the holding company was completing plans for its smelter, and equipment for the, construction of the plant was ordered. The holding company also increased its list of subsidiary mines, until it held title to over 200 claims comprising some 4,000 acres of land. Although the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was clearly the leading subsidiary within the umbrella group, sinking and exploration was also carried on in numerous of the company's other mines. More strikes were made in June, and although none were large enough to turn the mine from development into production, all were encouraging as they gave indications of an immense copper body just a little farther below the surface. The Bullfrog Miner reported towards the end of June that six shafts were working at the Greenwater Death Valley property, the deepest of which was now 500 feet. Miners were still scarce in Greenwater, and since contractors refused to work on crosscuts during the graveyard shift, the company was forced to cut back its operation to two daily shifts. "The success of this mine, which would lead to a smelter being built," concluded the Bullfrog Miner, "is most important for the Greenwater district." Further strikes of small copper deposits were reported in July, and late in that month, the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company made a shipment of two carloads (approximately forty tons) of its high-grade ore, which had been taken out of the small strikes during the past months. Following that shipment, the news from the mines decreased, and development slowed down somewhat as Schwab and other operators began to feel the effects of the Panic of 1907. Not until late October was the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company mentioned again, when it was reported that they had added ten more men to the payroll. By now the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company was employing 100 men in its combined operations, and more than half of them were working directly for Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company. In November, however, three of that company's shafts were closed, in order to economize on development work, and only three shafts were still in operation. An indication of some past troubles was alluded to in the Bullfrog Miner, when it mentioned that the Schwab property was resuming full-scale work. As the year closed out, developments seemed to be increasing once again, as the company let a contract for 500 feet of sinking in its main shaft. The shift from company work to contract work, though, was a ready indication that the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was beginning to feel the financial pinch. [16] By the beginning of 1908 the Greenwater boom had busted, and the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was one of the few still working in the district. Gone were the balmy days when companies were organized for $25,000,000: the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company quietly faded into the background, and no more word of smelter construction or railroad building was heard. Rather, operations were contracted, development was restricted to the most economical means, and the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company tried to save all its previous investments in a desperate search for ore. Happily, the company still had a fat treasury, due to wise management practices and the constant sale of company stock in previous days when prices had been high. As the new year opened, the main shaft at the property was approaching the 600-foot level, and progress was steady now that work had been concentrated on one shaft. The company reported in March, after two more months of work, that $125,000 was left in its treasury for further development work, and that its shaft was now 740 feet deep. Another contract was let at this time to sink 100 feet further. By the first of April, the shaft was down to 850 feet, by far the deepest of any in the district, and towards the end of April was approaching the magic 1000-foot level, where all the company's experts had predicted the giant copper body would be found As May ended, the shaft was down to 940 feet, and Superintendent Jerry O'Rourke optimistically told the Rhyolite Herald that "they will make a camp of Greenwater yet." On June 10th the 1000-foot point was finally reached, and true to prediction, ore was struck. The first assays on the copper body ran 5 to 6 percent copper, but no one could yet estimate how extensive the deposit was. This strike, as noted before, caused a minor rush back into the Greenwater District, as prospectors and companies who had let their titles lapse rushed back in to reclaim them. But within a week, the strike had proven to be no more than a small stringer or ore. Still, no one doubted that the presence of this small stringer indicated that there was a large body of copper within the vicinity, and the strike did prove that Greenwater was "not a surface proposition as has so often been claimed. The company was still confident that ore was in the ground, and stated in late June that in case ore is not struck in the crosscut which has been started from the 1,000-foot level, that the company will sink another 1,000 feet to demonstrate its theory that a body of copper ore exists in the locality. However, it is believed that the present crosscut will uncover commercial copper when it reaches its objective point." As July progressed, the company pursued that objective, via crosscuts from both the 500 and the 1,000-foot levels, and was apparently satisfied enough with the results of the search to finally apply for a patent to its claims. The application listed a total of thirty claims and thirteen fractions, for a total of over 515 acres. In the meantime, the crosscuts were continued, and although ore assaying 6 percent copper and eleven ounces of silver, for a total worth of $25 per ton, was discovered in the crosscut from the 500-foot level, nothing of importance was found at the deeper 1,000-foot level. Despite this discouraging result, the company kept working. Time and money, however, were beginning to press the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, and the work force was cut back until it was described in late October as a small force of men. Work was resumed in the main shaft in November, and by the end of the year, it had been sunk to nearly 1,100 feet. Small stringers of copper ore were found as the shaft went deeper, but nothing of commercial grade or extent could be found. [17] After a disappointing 1908, the new year opened on a more promising note for the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company. The drifts continued to find ore, its quality started to improve somewhat, and the Rhyolite Daily Bulletin reported in early January that "the situation in the Greenwater district is very encouraging." The paper again reported towards the middle of January that the company was bringing up buckets or ore, which was starting to appear in bunches, and "every indication points to a monster vein in the property that should soon be tapped." The Mining World picked up on that report, but cautioned that considerable work remains to be done to demonstrate the extent and value of these finds." But after years of fruitless searching for ore, it was hard to hold down the elation over finding copper, even though its commercial extent was not yet proven. Early in February the Bullfrog Miner reported that the recent discovery of sixty feet of 5 percent copper ore at the 1000-foot point of the shaft had caused the company to become "highly elated" over the discovery, and to push "developments vigorously." "On the proving of the new ore body," remarked the Bullfrog Miner in an understatement, "depends the future of the Greenwater Death Valley mine and practically of the camp of Greenwater. Hard on the heels of this discovery came another, as ore was finally found in the crosscut from the 1,000-foot level of the shaft, 200 feet out. This body was soon proven to be forty feet in width, which was stilt not enough to warrant commercial production, but much more than enough to warrant further exploration and development. "The find has caused all kinds of excitement around Greenwater," reported the Rhyolite Daily Bulletin, "and all indications point to a big revival in the mining industry." The Bullfrog Miner agreed, and reported that the "camp of Greenwater is on the rise from all indications Parties with holdings there are putting forth more zeal in the development than has been shown for over a year." With the revival of hopes, the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company, which still held control of the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company, released its annual report for the year ending December 31, 1908. The holding company had a cash balance of $138,136 at the end of that year, which included $49,099 in the treasury of the United Greenwater Copper Company and $87,136 in the treasury of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company. Since the United Greenwater had long ago ceased work, its treasury funds were available for application towards the continuing development work on the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company's mines. The parent company, it was announced, owned or controlled 96 percent of the capital stock of the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper, the United Greenwater Copper, and the El Capitan Copper Mining Company. All but the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company, however, were idle. Pushing hard upon its discoveries, that company continued its work through March. By the middle of that month, the main shaft was down to 1,220 feet and was going for 1,500, which was now seen as the point of decision. Fifteen men were employed at the mine. Work was temporarily halted in early April, when Fred Kelly, a 39-year old miner, fell to his death in the shaft of the mine, but was soon continued, and in late April and early May, more small copper bodies were found. By the middle of May, with the shaft approaching the 1,300-foot mark, the future of the mine was still indecisive, for although the "usual indications of copper are present . . . . no commercial ore bodies have been encountered." The Bullfrog Miner reported at this time that the total treasury of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company, based upon its earlier annual report, would be sufficient for more than four more years of development work, based upon the average costs of $2,500 per month at the mine. Such an expenditure would be impractical, however, for everyone agreed that if copper was not found by the 1,500-foot depth, the mine would be abandoned, since copper below that level, no matter how rich, would be very expensive to mine. But the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company and its parent holding company were both in rather good financial shape, and even though ore was not found, the price of stock in both companies began to rise, going from 4¢ to 9¢ per share. The reason for the trading, explained the Rhyolite Herald was the tact that if the company quit work, the remaining treasury funds would be divided among the holders of its outstanding stock, which made that stock worth a few cents per shares. Shareholders, in other words, now hoped that the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company would either find ore quickly, or else close down quickly and distribute the remaining funds. On July 24th, it looked like the latter would be the option taken. Work was halted at the mine, for the shaft had reached the 1,400-foot level, and the present hoisting plant at the property did not have the capacity to raise rock from any lower down. The superintendent asked for instructions, giving the company the options of purchasing a new hoist for deeper sinking, of crosscutting from the 1400-foot level, or of shutting down the mine. After some thought the company decided to purchase a larger hoist, and while awaiting its arrival, to crosscut at the bottom of the shaft. But the crosscutting soon proved futile, and for some reason the company reversed its decision, for the new hoist was never ordered. Work gradually slowed down at the mine, and finally, on September 1st, was halted. The work force was laid off. After sinking to a final depth of 1439 feet below the surface, the deepest shaft in the Death Valley region, the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company finally gave up its search for copper ore and abandoned its mine. Greenwater was now totally dead, for this was the last company operating in the district. The Inyo Register printed the obituary for both the mine and the district: "With the cessation of all work at the Greenwater Death Valley mine, the once thriving camps of Greenwater and Furnace Creek, California, have been given over to the reign of the coyotes. There is scarcely a man to be found in the entire district, and locally it is considered extremely doubtful that the Schwab company will ever resume work at the mine, which was once pronounced a bonanza." Ironically, with the cessation of work at Greenwater, shares in the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company shot up from 7¢ to 11¢ each, as stockholders anticipated the splitting of the remaining treasury funds. The stockholders, however, were doomed to disappointment, for the holding company decided to invest the remaining funds in other mining districts rather than dissolve the company, and for the next several years, sporadic reports of the company could be found from gold districts in Nevada and California, where they tried their luck. Unfortunately, the other districts proved no more fruitful than had Greenwater, and the company eventually went broke. In the meantime, however, the Rhyolite Herald had nothing but praise for the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, for in Greenwater it had done all that could be expected and more to try to prove the benefits of the once highly praised district. The management of the company, said the Herald, had always been honest and above board, and reasonable men could have been expected to give up long before they had. No one should he able to complain about the conduct of its business in the Greenwater District. Shortly after the mine was closed down, contracts were let to haul the machinery and equipment out of the district for use elsewhere, a job which was expected to take five or six weeks. The cannibalization of the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Mine was so complete that the timbers were even stripped from the shafts and brought up for use again elsewhere. The company's property was totally abandoned, and in June of 1910 reverted to county control, when the once mighty Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company failed to pay $10.85 in county taxes on its numerous mining claims in the district. History from OldCompany.com and SavingsBonds.pro (collectible Savings Bonds website)

Certificate

Back of Certificate

History from the National Park Service During the short and spectacular Greenwater boom, fully seventy-three mining companies were incorporated within the district, and literally scores of smaller mines and prospects were opened Papers have been located for thirty-three of the companies which did incorporate, which show their combined capitalization value to be over $76,000,000. Although the exact capitalization totals of the other forty incorporated companies cannot be determined, the minimum standard capitalization for the time period was $1,000,000 per company, which would give us a total capitalization value of the Greenwater district mines of over $116,000,000. This total, of course, in no way reflects the actual amount of money spent in the district, but it does give some idea of the amazingly vast amounts which investors and promoters hoped to reap from the rich copper ores of Greenwater. The Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company consisted of sixteen claims and five fractions. The development workstarted with three shafts, one on the east end, one at the center and one at the west end of the property. The deepest working is on the Copper Queen claim, consisting of a shaft, down 70 feet. The veins on the different properties vary in width from fifteen to forty feet. Greenwater Death and Valley Copper Company A major mine in the Greenwater district, the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company, which was owned and operated by one of the great business magnates of the early twentieth century, Charles Schwab. After making his fortune in steel, Schwab had been attracted to the gold fields of Nevada following the Tonopah and Goldfield booms, and, as we have seen, dabbled constantly in mines in and around the Bullfrog area. When the Greenwater rush began, Schwab, like most major operators in the area, rushed to the site in order to capitalize on what seemed to be the biggest boom of them all. Schwabs activities are hard to follow during the early days of the boom, since he had several agents in and around the mining towns of Death Valley who bought and sold mining properties on his behalf. For a short time in early 1906, Schwab held an interest in the Funeral Range Copper Company, but it was shortly sold, apparently because he was unable to gain outright control of the company. In July of 1906, Schwab began buying up mining claims in his own right. Schwab paid $180,000 to Arthur Kunze and his partners for a group of sixteen claims, and on August 10, 1906, the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was incorporated. The capitalization was for $3,000,000, one of the largest capitalizations in the district, and Schwab retained majority control of the company, even though his name does not appear as a member of the board of directors. The company by this time held title to 300 acres of ground, and announced that the installation of mining machinery and the inauguration of an extensive development campaign would soon start. In addition to its mineral holdings in Greenwater, the Schwab company also owned water rights at Ash Meadows, and preliminary plans were announced to install a pumping and power station in that vicinity. Lumber and supplies began to flow into the company's property at Greenwater and work began. According to the usual procedure a limited amount of Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company stock was offered for sale in Rhyolite and other mining towns of the west, and by the end of August, the main shaft of the mine was down to 100 feet in depth, and work was started on two other shafts. The company ordered three gas hoists to facilitate the sinking. With the organization of a company such as this, with a man of Schwab's reputation behind it, the local newspapers immediately began to follow the progress of the company. The Bullfrog Miner reported in late September that the company was already employing forty miners on its property. In addition, it said, the company had ordered three gas hoists (of 25, 40 and 50-horsepower), which would easily give it the largest hoisting capacity in the district. These first indications of development work were quite promising, and the Inyo Independent reported towards the end of September that the company had "good ore. Although the Furnace Creek Copper Company was the darling stock of the Greenwater District, Greenwater Death Valley Copper did not do poorly. The attraction of the Schwab name--even though he had never attempted copper mining before--plus the good location and the obvious intent of the company to develop its property extensively, caused the price of its stock to soar upwards, until it was selling for $2 per share in late September, twice its par value. By the end of that month, the three new hoists had arrived at the mine and were being placed above their shafts, two of which were already below the 100-toot level. The company added a few more claims to its property list in early October, and spurred by this and other mysterious activities, the newspapers soon picked up the smell of something big. Since the biggest thing they could imagine would be a combination of Clark's and Schwab's mines--the two largest in the district--incessant rumors circulated of a merger between the two powerful operators. The rumors caused especially heavy trading of the stocks of both companies in Boston and New York, and the rumors became so proliferant that the papers began to believe themselves. The Inyo Independent reported in mid-October that the merger between the companies was practically final, since the main points affecting it had been settled between Clark and Schwab. When another month passed, however, without any merger announcements, the Bullfrog Miner revised its estimate and reported that difficulties had arisen, which had delayed the consolidation. In the meantime, the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was working hard, and early in November began taking shipping ore out of one of its shafts. By this time the company had two of its shafts below 100 feet, a third below 50 feet, and had built two comfortable frame offices on its property. Work continued through the rest of 1906, and by early December the two deeper shafts were at the 200-level, and the Greenwater Death Valley Copper company had emerged as one of the largest operations in the district. Then, on December 15th, the long-anticipated merger took place. Unfortunately, the papers had been speculating about the wrong companies, however, for the Furnace Creek Copper Company had no part in the merger. Instead, a consolidation was announced, of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper, the United Greenwater Copper and several unincorporated mines owned by John Brock and some Philadelphia financiers. The new merger company was named the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines and Smelting Company, and had a capitalization of $25,000,000, with five million shares worth $5 each. It was easily the largest incorporation that the Death Valley region had ever seen. The new company was a holding corporation, and as such bought up the controlling interests in the companies it took over. The stock distribution in the new company was based upon the amount of stock which had been sold in the older companies, and 68 percent of the merger company's stock went to buy out the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, 18 percent to the United Greenwater, and the rest to the owners of the unincorporated mines. Charles Schwab, it was definitely pointed out, was in control of the holding company, and plans were announced for the erection of a smelter at Ash Meadows, where the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company already had water rights. In addition, the holding company announced that it would build a railroad from the smelter site to the Greenwater mines. A smelting expert was hired for $25,000 per year to supervise the selection of the construction site and the construction of the plant, and hopes were raised that the smelter would be running within a year. Under the management arrangement of the holding company, however, the subsidiary companies under its control would continue to work on their own, retaining their names, identities and management--subject, of course, to the approval of Schwab and the parent company. Thus the mines continued to explore and develop their own deposits, and the holding company was used for a pooling of resources and capital, which would be necessary in order to finance the capital expenditures which were proposed. [15] Copper Queen shaft Illustration 216. an early view of the Copper Queen shaft of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, ca. December 1906. This was the shaft which was ultimately sunk to the depth of over 1400 feet. In this view, however, work has barely startd, and the miners are still using a crude hand whim to raise the rock to the surface. The young town of Kunze may be seen in the background. Photo courtesy Nevada Historical Society. Copper Queen shaft Illustration 217. Another view of the same shaft, this one taken below ground, where an intermediate hand whim was being used. The man sitting at the right, with suspenders, notebook and pen in pocket, is undoubtedly the mine superintendent. He may also be seen in the background in the preceeding picture. Photo courtesy Nevada Historical Society. Under the impetus of the new merger arrangements, and with the Greenwater boom at its very peak, the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company opened 1907 in impressive style, increasing its work force to nearly fifty men! Two more gas hoists were added to the property, bringing the total to five hoists pumping away over five separate shafts. Four of the shafts were over 100 feet in depth, and the deepest one had reached 125 feet. By early February the holding company announced that construction plans were completed for its smelter, which would cost $1,500,000 to build, and reaffirmed that a rail line would be constructed between the smelter site and the mines. The Death Valley Chuck-Walla reported that the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company had itself spent over $100,000 since starting work in August of 1906, and now had all five shafts down past the 100-foot point. Labor costs alone were running the company $10,000 a month to pursue its vigorous campaign. The deepest shaft was now down to 140 feet, and an air compressor had been ordered to force air down to the men working below ground. Early in March the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company added more mines to its holdings, including those of the Greenwater El Capitan Copper company. Construction on the smelter was slated to start within sixty days, and survey work for the railroad spur was started. By the middle of that month, the deepest shaft on the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company's property was near the 300-foot level, and two others were down to 275 and 200 feet. Three shifts were working around the clock, a machine shop had been installed at the central shaft, an assay office was built, and a sawmill was under construction, to facilitate the shaping of timbers for the deep mine shafts. The rapid exploitation of the company's property continued through April, and the payroll was increased to 75 men. By the 19th of that month the deepest shaft was down 475 feet, and had fairly good copper ore (3%) at the bottom. Sinking kept pace in the other shafts, and towards the end of April, four of the company's five working shafts were below 40:0 feet. As May progressed, crosscuts were run from several of the shafts, as exploratory measures, and by the end of May another small strike was reported at the 485-foot level in one of the shafts. In the meantime the holding company was completing plans for its smelter, and equipment for the, construction of the plant was ordered. The holding company also increased its list of subsidiary mines, until it held title to over 200 claims comprising some 4,000 acres of land. Although the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was clearly the leading subsidiary within the umbrella group, sinking and exploration was also carried on in numerous of the company's other mines. More strikes were made in June, and although none were large enough to turn the mine from development into production, all were encouraging as they gave indications of an immense copper body just a little farther below the surface. The Bullfrog Miner reported towards the end of June that six shafts were working at the Greenwater Death Valley property, the deepest of which was now 500 feet. Miners were still scarce in Greenwater, and since contractors refused to work on crosscuts during the graveyard shift, the company was forced to cut back its operation to two daily shifts. "The success of this mine, which would lead to a smelter being built," concluded the Bullfrog Miner, "is most important for the Greenwater district." Further strikes of small copper deposits were reported in July, and late in that month, the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company made a shipment of two carloads (approximately forty tons) of its high-grade ore, which had been taken out of the small strikes during the past months. Following that shipment, the news from the mines decreased, and development slowed down somewhat as Schwab and other operators began to feel the effects of the Panic of 1907. Not until late October was the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company mentioned again, when it was reported that they had added ten more men to the payroll. By now the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company was employing 100 men in its combined operations, and more than half of them were working directly for Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company. In November, however, three of that company's shafts were closed, in order to economize on development work, and only three shafts were still in operation. An indication of some past troubles was alluded to in the Bullfrog Miner, when it mentioned that the Schwab property was resuming full-scale work. As the year closed out, developments seemed to be increasing once again, as the company let a contract for 500 feet of sinking in its main shaft. The shift from company work to contract work, though, was a ready indication that the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was beginning to feel the financial pinch. [16] By the beginning of 1908 the Greenwater boom had busted, and the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company was one of the few still working in the district. Gone were the balmy days when companies were organized for $25,000,000: the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company quietly faded into the background, and no more word of smelter construction or railroad building was heard. Rather, operations were contracted, development was restricted to the most economical means, and the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company tried to save all its previous investments in a desperate search for ore. Happily, the company still had a fat treasury, due to wise management practices and the constant sale of company stock in previous days when prices had been high. As the new year opened, the main shaft at the property was approaching the 600-foot level, and progress was steady now that work had been concentrated on one shaft. The company reported in March, after two more months of work, that $125,000 was left in its treasury for further development work, and that its shaft was now 740 feet deep. Another contract was let at this time to sink 100 feet further. By the first of April, the shaft was down to 850 feet, by far the deepest of any in the district, and towards the end of April was approaching the magic 1000-foot level, where all the company's experts had predicted the giant copper body would be found As May ended, the shaft was down to 940 feet, and Superintendent Jerry O'Rourke optimistically told the Rhyolite Herald that "they will make a camp of Greenwater yet." On June 10th the 1000-foot point was finally reached, and true to prediction, ore was struck. The first assays on the copper body ran 5 to 6 percent copper, but no one could yet estimate how extensive the deposit was. This strike, as noted before, caused a minor rush back into the Greenwater District, as prospectors and companies who had let their titles lapse rushed back in to reclaim them. But within a week, the strike had proven to be no more than a small stringer or ore. Still, no one doubted that the presence of this small stringer indicated that there was a large body of copper within the vicinity, and the strike did prove that Greenwater was "not a surface proposition as has so often been claimed. The company was still confident that ore was in the ground, and stated in late June that in case ore is not struck in the crosscut which has been started from the 1,000-foot level, that the company will sink another 1,000 feet to demonstrate its theory that a body of copper ore exists in the locality. However, it is believed that the present crosscut will uncover commercial copper when it reaches its objective point." As July progressed, the company pursued that objective, via crosscuts from both the 500 and the 1,000-foot levels, and was apparently satisfied enough with the results of the search to finally apply for a patent to its claims. The application listed a total of thirty claims and thirteen fractions, for a total of over 515 acres. In the meantime, the crosscuts were continued, and although ore assaying 6 percent copper and eleven ounces of silver, for a total worth of $25 per ton, was discovered in the crosscut from the 500-foot level, nothing of importance was found at the deeper 1,000-foot level. Despite this discouraging result, the company kept working. Time and money, however, were beginning to press the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, and the work force was cut back until it was described in late October as a small force of men. Work was resumed in the main shaft in November, and by the end of the year, it had been sunk to nearly 1,100 feet. Small stringers of copper ore were found as the shaft went deeper, but nothing of commercial grade or extent could be found. [17] After a disappointing 1908, the new year opened on a more promising note for the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company. The drifts continued to find ore, its quality started to improve somewhat, and the Rhyolite Daily Bulletin reported in early January that "the situation in the Greenwater district is very encouraging." The paper again reported towards the middle of January that the company was bringing up buckets or ore, which was starting to appear in bunches, and "every indication points to a monster vein in the property that should soon be tapped." The Mining World picked up on that report, but cautioned that considerable work remains to be done to demonstrate the extent and value of these finds." But after years of fruitless searching for ore, it was hard to hold down the elation over finding copper, even though its commercial extent was not yet proven. Early in February the Bullfrog Miner reported that the recent discovery of sixty feet of 5 percent copper ore at the 1000-foot point of the shaft had caused the company to become "highly elated" over the discovery, and to push "developments vigorously." "On the proving of the new ore body," remarked the Bullfrog Miner in an understatement, "depends the future of the Greenwater Death Valley mine and practically of the camp of Greenwater. Hard on the heels of this discovery came another, as ore was finally found in the crosscut from the 1,000-foot level of the shaft, 200 feet out. This body was soon proven to be forty feet in width, which was stilt not enough to warrant commercial production, but much more than enough to warrant further exploration and development. "The find has caused all kinds of excitement around Greenwater," reported the Rhyolite Daily Bulletin, "and all indications point to a big revival in the mining industry." The Bullfrog Miner agreed, and reported that the "camp of Greenwater is on the rise from all indications Parties with holdings there are putting forth more zeal in the development than has been shown for over a year." With the revival of hopes, the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company, which still held control of the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company, released its annual report for the year ending December 31, 1908. The holding company had a cash balance of $138,136 at the end of that year, which included $49,099 in the treasury of the United Greenwater Copper Company and $87,136 in the treasury of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company. Since the United Greenwater had long ago ceased work, its treasury funds were available for application towards the continuing development work on the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company's mines. The parent company, it was announced, owned or controlled 96 percent of the capital stock of the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper, the United Greenwater Copper, and the El Capitan Copper Mining Company. All but the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company, however, were idle. Pushing hard upon its discoveries, that company continued its work through March. By the middle of that month, the main shaft was down to 1,220 feet and was going for 1,500, which was now seen as the point of decision. Fifteen men were employed at the mine. Work was temporarily halted in early April, when Fred Kelly, a 39-year old miner, fell to his death in the shaft of the mine, but was soon continued, and in late April and early May, more small copper bodies were found. By the middle of May, with the shaft approaching the 1,300-foot mark, the future of the mine was still indecisive, for although the "usual indications of copper are present . . . . no commercial ore bodies have been encountered." The Bullfrog Miner reported at this time that the total treasury of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company, based upon its earlier annual report, would be sufficient for more than four more years of development work, based upon the average costs of $2,500 per month at the mine. Such an expenditure would be impractical, however, for everyone agreed that if copper was not found by the 1,500-foot depth, the mine would be abandoned, since copper below that level, no matter how rich, would be very expensive to mine. But the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company and its parent holding company were both in rather good financial shape, and even though ore was not found, the price of stock in both companies began to rise, going from 4¢ to 9¢ per share. The reason for the trading, explained the Rhyolite Herald was the tact that if the company quit work, the remaining treasury funds would be divided among the holders of its outstanding stock, which made that stock worth a few cents per shares. Shareholders, in other words, now hoped that the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company would either find ore quickly, or else close down quickly and distribute the remaining funds. On July 24th, it looked like the latter would be the option taken. Work was halted at the mine, for the shaft had reached the 1,400-foot level, and the present hoisting plant at the property did not have the capacity to raise rock from any lower down. The superintendent asked for instructions, giving the company the options of purchasing a new hoist for deeper sinking, of crosscutting from the 1400-foot level, or of shutting down the mine. After some thought the company decided to purchase a larger hoist, and while awaiting its arrival, to crosscut at the bottom of the shaft. But the crosscutting soon proved futile, and for some reason the company reversed its decision, for the new hoist was never ordered. Work gradually slowed down at the mine, and finally, on September 1st, was halted. The work force was laid off. After sinking to a final depth of 1439 feet below the surface, the deepest shaft in the Death Valley region, the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company finally gave up its search for copper ore and abandoned its mine. Greenwater was now totally dead, for this was the last company operating in the district. The Inyo Register printed the obituary for both the mine and the district: "With the cessation of all work at the Greenwater Death Valley mine, the once thriving camps of Greenwater and Furnace Creek, California, have been given over to the reign of the coyotes. There is scarcely a man to be found in the entire district, and locally it is considered extremely doubtful that the Schwab company will ever resume work at the mine, which was once pronounced a bonanza." Ironically, with the cessation of work at Greenwater, shares in the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company shot up from 7¢ to 11¢ each, as stockholders anticipated the splitting of the remaining treasury funds. The stockholders, however, were doomed to disappointment, for the holding company decided to invest the remaining funds in other mining districts rather than dissolve the company, and for the next several years, sporadic reports of the company could be found from gold districts in Nevada and California, where they tried their luck. Unfortunately, the other districts proved no more fruitful than had Greenwater, and the company eventually went broke. In the meantime, however, the Rhyolite Herald had nothing but praise for the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, for in Greenwater it had done all that could be expected and more to try to prove the benefits of the once highly praised district. The management of the company, said the Herald, had always been honest and above board, and reasonable men could have been expected to give up long before they had. No one should he able to complain about the conduct of its business in the Greenwater District. Shortly after the mine was closed down, contracts were let to haul the machinery and equipment out of the district for use elsewhere, a job which was expected to take five or six weeks. The cannibalization of the Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Mine was so complete that the timbers were even stripped from the shafts and brought up for use again elsewhere. The company's property was totally abandoned, and in June of 1910 reverted to county control, when the once mighty Greenwater and Death Valley Copper Company failed to pay $10.85 in county taxes on its numerous mining claims in the district. History from OldCompany.com and SavingsBonds.pro (collectible Savings Bonds website)