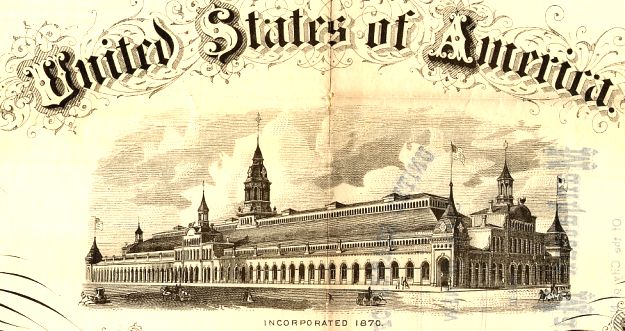

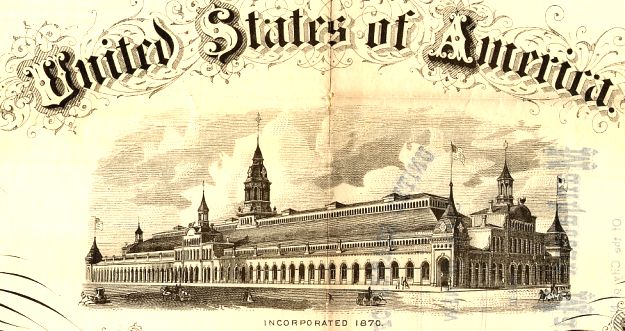

Beautifully engraved Second Mortgage Convertible Bond certificate from the Manhattan Market Company issued in 1871. This historic document was printed by Hatch & Co. and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of a large market building. This item has the signatures of the Company's President, Treasurer and Trustee and is over 141 years old.

Certificate Vignette

Officers Signatures History from "New York and Its Institutions, 1609-1871" by REV. J. F. RICHMOND printed in 1872. The Manhattan Market Company, chartered a year and a half since, are now erecting the largest and finest market building yet undertaken on the island. It stands on the block between Thirty-fourth and Thirty-fifth streets, Eleventh and Twelfth avenues. The main structure, which is of iron, stone, and Philadelphia brick, is 800 feet long and 200 feet deep, and will contain 800 stands. The interior of the structure is 80 feet high, well lighted, and if Washington is ever removed, this appears certain to become the principal wholesale market of the city. The contractors have agreed to complete it by the first of October, 1871. Others are to follow under the direction of this company. In 1859, Philadelphia was in the throes of a movement to consolidate city government and to remove from the city disorder, n'er-do-wells, and odors offensive to middle-class folk. As a growing mill and port city, Philadelphia needed cleanliness and good order; railroad companies--the emerging star of the city's economy--needed access to streets then blocked by public markets. Consequently, the city demolished the well-known High Street Market, and the legislature authorized incorporation of thirteen privately held market house companies. An additional seven were incorporated before 1862. The houses built by the companies were immense and grand, and stalls within the market houses commanded high rents, at least initially. But the companies struggled to survive. Poor management and an over-abundance of market houses led to the failure of firms. The relatively short lifespan of many private market companies in Philadelphia did not discourage other cities from demolishing public markets in favor of off-street market houses. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania had incorporated over 100 private market houses. The epoch of laissez-faire and government friendliness toward the corporation had begun to shape the distribution of food. By the 1880s, private and public markets in the commonwealth developed a national reputation for success. In 1871, the New York Assembly incorporated a private market house--the Manhattan Market Company--in New York City. Yet New York's affection for public markets did not diminish. Indeed, in 1871, the leading proponent of public market houses, De Voe, was named superintendent of markets in the city, a position he held for a decade. Even as the Manhattan Market Company began its short-lived operations, De Voe set about reforming the management of public markets to ensure their long life. Largely because of De Voe, public markets occupied a more prominent place in New York City than in Philadelphia. When Philadelphia and New York City inaugurated private markets, local governments around the country did not follow suit. Public markets provided a source of income to cities; tragedy had proven that deregulated food supplies could pose a public health risk; and cities remained interested supplying working men and women with affordable food. Even as unregulated, suburban markets proliferated, cities continued to sustain public markets. In fact, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, in part spurred on by Horace Capron, commissioner of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, who was intensely interested in improving the food supply chain, cities strove to extend and incorporate public market houses into the urban landscape. Technological improvements and the exponential growth of railroads gave new life to the municipal market, and as the Progressive era began the federal government and the National Municipal League engaged in a national campaign to improve public markets. Tangires locates her text appropriately in the historiography of the city and reform movements, but the historical context for events she describes is, at times, vague and elliptical. For historians of the nineteenth century, the city, and reform, the context will be apparent, although other scholars may be left with questions. That nagging criticism, however, points to Tangires's greatest achievement: in a handsomely illustrated and well-written book, she constructs an argument about specific market houses and cities that nineteenth-century historians and general readers interested in those places will appreciate and understand.

Certificate Vignette

Officers Signatures