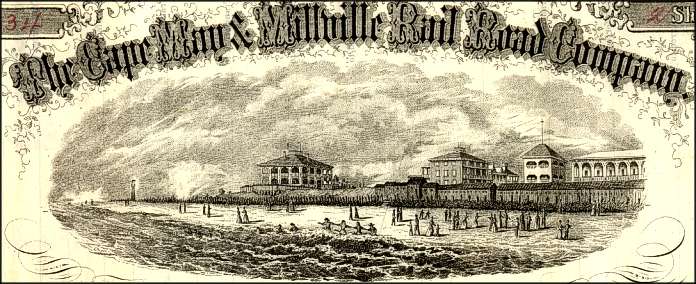

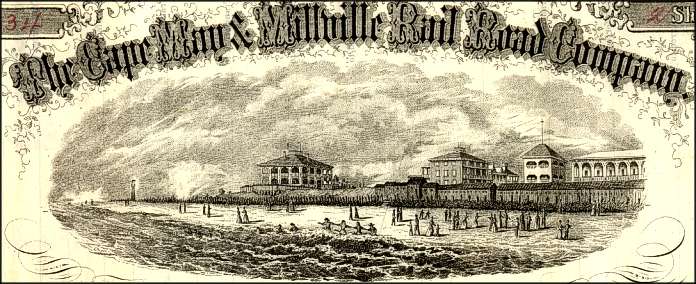

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Cape May & Millville Rail Road Company issued no later than 1871. This historic document has an ornate border around it with a vignette of beachfront town with people on the beach and in the water and a lighthouse in the background. This item is hand signed by the company's president and treasurer and is over 137 years old. This certificate looks much nicer in person than the scan indicates. The certificate's engraver is P. S. Duval & Son, Lith, Philadelphia. Cut-cancelled.

Certificate Vignette Below is an article written about Cape May History: Cape May, New Jersey, America's first resort. By Judy P. Sopronyi Property for sale..."pleasantly situated, open to the sea, in the...County of Cape May, within one Mile and a Half of the seashore, where Numbers resort for Health, and bathing in water; and this Place would be very convenient for taking in such People." -- Advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette, July 1766 It's hard to imagine people flocking to the beach back in the days of powdered wigs and buckled shoes. Try, if you can, to conjure up an image of our forefathers and foremothers in beach attire. But they did go to the beach, and the place they chose--years before they were even thinking about independence from Mother England--was Cape May at the southern tip of New Jersey. Bounded by the Delaware Bay to the west and the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Cape May still lures summer visitors with sea, sand and balmy breezes. Another strong draw is history. As the first and oldest resort in the United States, this pretty little town, decked out in all possible elaborations of Victorian gingerbread, has an unmistakable air of the past. That Victorian finery sported by Cape May's inns and bed-and-breakfasts looks positively modern when you consider the early days of European settlement here in the latter half of the 1600s, when water was something you navigated, and farming, whaling and shipbuilding were the trades of the day. But the lure of sand, sea and sun will not be denied, and by the early 1800s Philadelphians were making their way to New Jersey's cape in droves. In 1801, innkeeper Ellis Hughes wooed them with his advertisement of "Seashore Entertainment at Cape May" in the Philadelphia Aurora and General Advertiser: "The situation is beautiful, just on the confluence of Delaware Bay with the Ocean in sight of the Light-house, and affords a view of shipping which enters and leaves the Delaware. Carriages may be driven along the margin of the Ocean for miles; and the wheels will scarcely make any impression upon the sand, the slope of the shore is so regular that persons may wade out a great distance. It is the most beautiful spot that citizens can retire to in the hot season." Philadelphians weren't the only ones who knew a good summer place when they saw one. Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, New York and the rest of Pennsylvania and New Jersey sent their share of vacationers. From the South, ships carrying goods to the North and abroad also carried planters' families and dropped them off at Cape May on the way out, picking them up on the return trip. Unless you arrived by sailing ship, getting to Cape May wasn't particularly easy in those early years. There was some roadbuilding in the late 1700s, and a weekly stagecoach ran from Camden (then called Cooper's Ferry), New Jersey, down to Cape Island. (The original name for Cape May City was Cape Island; it wasn't really an island, though Cold Spring Inlet, Cape Island Creek and Cape May Harbor almost cut it off from the rest of the peninsula. They still do, only now Cold Spring Inlet is the Cape May Canal.) In the 1820s, steamboats brought passengers from Philadelphia and Delaware on a regular schedule. Not until the dark Civil War year of 1863 did the Cape May & Millville Railroad reach the cape, getting Philadelphians to sea and sand in a mere 3 1/2 hours. By the turn of the century, a ferry linked Cape May and Lewes, Delaware, but it was an on-again, off-again venture. Once pleasure seekers got to the cape, local innkeepers were prepared to accommodate them, to an extent. In his Cape May County, New Jersey: The Making of an American Resort Community, Jeffery M. Dorwart writes of "at least three licensed public houses, and probably one unlicensed house of entertainment--the Cape May County grand jury indicted Memucan Hughes in 1799 for causing a public nuisance." To keep up with the growing influx of visitors, entrepreneurs built big wooden hotels, but they weren't enough. In 1844, Camden lawyer and newspaperman Isaac Mickle reported, "We arrived at the Island about four o'clock, and found it so crowded that Miller could do no better for us than give us a room to sleep in out in the country two miles." Cape May was hopping. The social elite of Philadelphia and Delaware deemed it the "in" place to go, and it rivaled Newport, Rhode Island, and Saratoga Springs, New York, as the summer destination of choice. The "in crowd" has always been studded with celebrities, and the famous found themselves "On the Way to Cape May," too. Senator Henry Clay sought distraction in Cape May after the death of his infant son in 1847. U.S. Presidents Franklin Pierce, Chester A. Arthur and Ulysses S. Grant wiled away some leisure time in Cape May. Philadelphia department store magnate and U.S. Postmaster General John Wanamaker had a cottage in Cape May, and U.S. President and Mrs. Benjamin Harrison were his guests there in 1890-91. Actress Lily Langtry, writer Bret Harte, American Red Cross founder Clara Barton and Mexican Empress Carlotta all visited Cape May, and march composer John Philip Sousa directed his band on the lawn of Congress Hall, which still stands. In 1905, automotive leaders Louis Chevrolet and Henry Ford vied with others to win a car race, spinning their wheels on the same firm sand Ellis Hughes wrote about in 1801, before a crowd of 20,000. "Henry Ford came in last," writes Dorwart, "and sold his touring car ... in order to pay his bill at the Stockton Hotel." But Cape May's success didn't follow a steady upward curve. The Civil War played havoc with tourism, hurricanes had their way with the town, and in 1878 a major fire destroyed a huge chunk of Cape May's wooden architecture. When the citizenry rebuilt, they chose not to update but to recreate the same plain styles that had fallen to flames, according to Dorwart, although today the town is the epitome of fancy Victorian ornamentation, outside and in. The fire destroyed 35 acres of little Cape May, and rebuilding wasn't enough to pull it out of its 1870s slump. Up the coast, Atlantic City was thriving. Jealous Cape May businessmen complained about the stubborn refusal of local government to grant liquor licenses to help them compete with Atlantic City's double draw of seawater and firewater. Cape May's fortunes saw fat and lean times into the 20th century, waxing and waning with Prohibition and World Wars. Left-over from World War II on the beach near the Cape May Point Lighthouse is an antisubmarine surveillance station, and the road from Cape May to the Point passes a tall tower used as an enemy aircraft lookout. Post-war prosperity put money in pockets and just about everybody into an automobile. Many vacationers took the new Garden State Parkway down to Cape May and brought the town another boom in the 1950s, a decade that ushered in the resort's first motel in 1952. But ten years later, a hurricane devastated the area and eroded hundreds of feet of beachfront, leaving the submarine surveillance station at Cape May Point completely above the water line. Time for another slump in fortunes. Uncle Sam came to the rescue in the form of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's Urban Renewal program. In 1967, city fathers got funding for Cape May's Victorian District Urban Renewal Project. In the town's tired, time-worn core, hopelessly dilapidated structures were torn down, giving the rest a new lease on life and earning the area a designation of "Historic District" on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. When the 1980s infatuation with Victorian architecture and interior decor heated up, Cape May was set to deliver exactly that. In charming old houses freshly repainted with authentic Victorian colors, new restaurants, shops and bed-and-breakfast inns welcomed throngs to once-again-popular Cape May. And it looks like popularity will be the town's destiny for many years to come. Historic ambiance, sun and sea rarely combine in such a pretty little package. Walk the Historic District and enjoy the diversity of architecture. It's said that in the Victorian era, design originality was important; the incredible variety of architectural ornamentation on old Cape May houses proves it. Painting a house white was a no-no then, and you can tell that restorers of many of the Victorian buildings had fun choosing paint colors--some combinations are startling to folks used to the limited, pale palette of today's buildings. Cape May has earned the designation "Tree City U.S.A.," so you can imagine the leafy green arching over the streets, inviting walking and bicycling. Out of the shade, the sea laps at Cape May's sandy doorstep while ships pass on the far horizon, and maybe a whale or two if you're lucky. You'll probably enjoy your journey "On the Way to Cape May," but the best part comes when you get there. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Judy P. Sopronyi, associate editor of Historic Traveler, was formerly managing editor of another Cowles magazine, Early American Life. See http://www.thehistorynet.com/HistoricTraveler/articles/1998/06982_text.htm for article.

Certificate Vignette