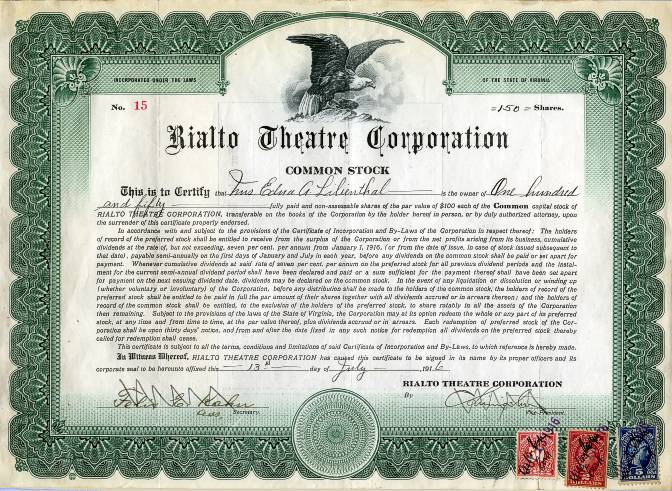

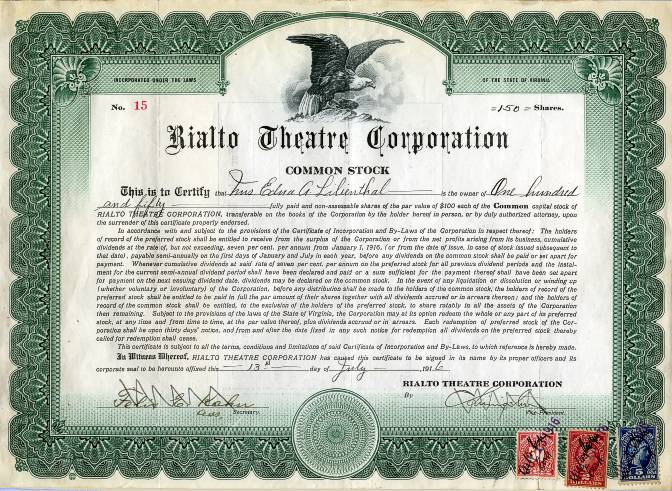

Beautiful SCARCE stock certificate from the Rialto Theatre Corporation issued in 1916. This historic has an ornate border around it with an image of an eagle. This item has the signatures of the Company's officers, Crawford Livingston (jr) and Felix Kahn.

Certificate

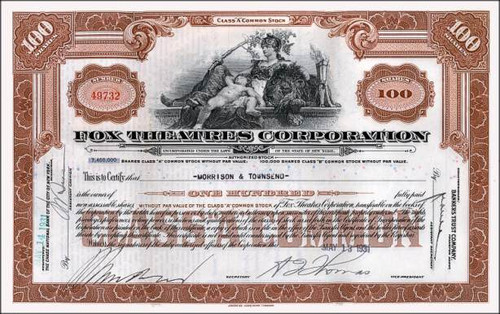

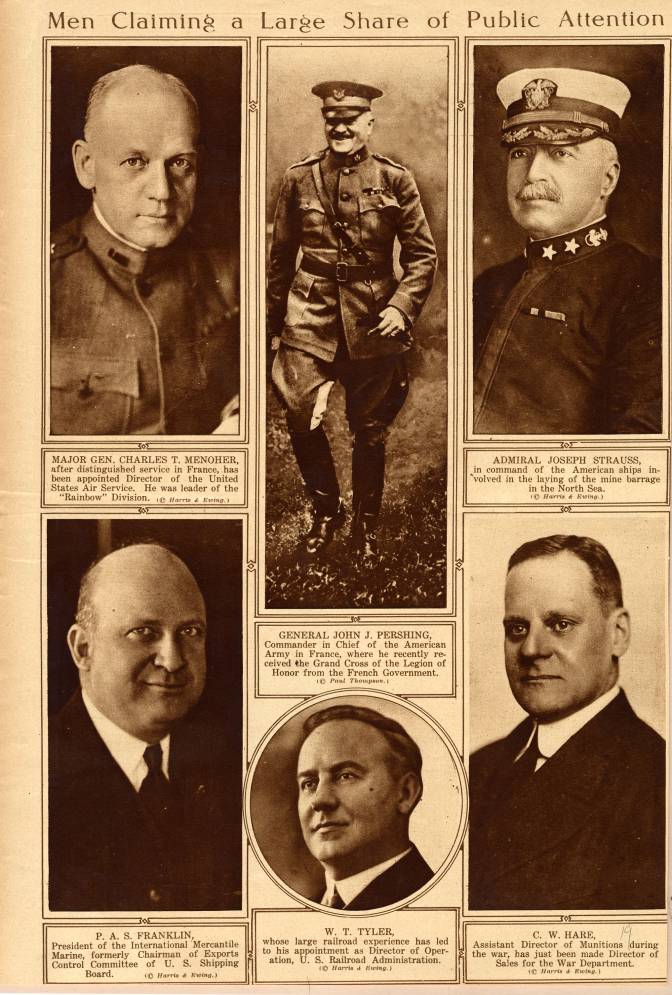

Old Picture shown for illustrative purposes

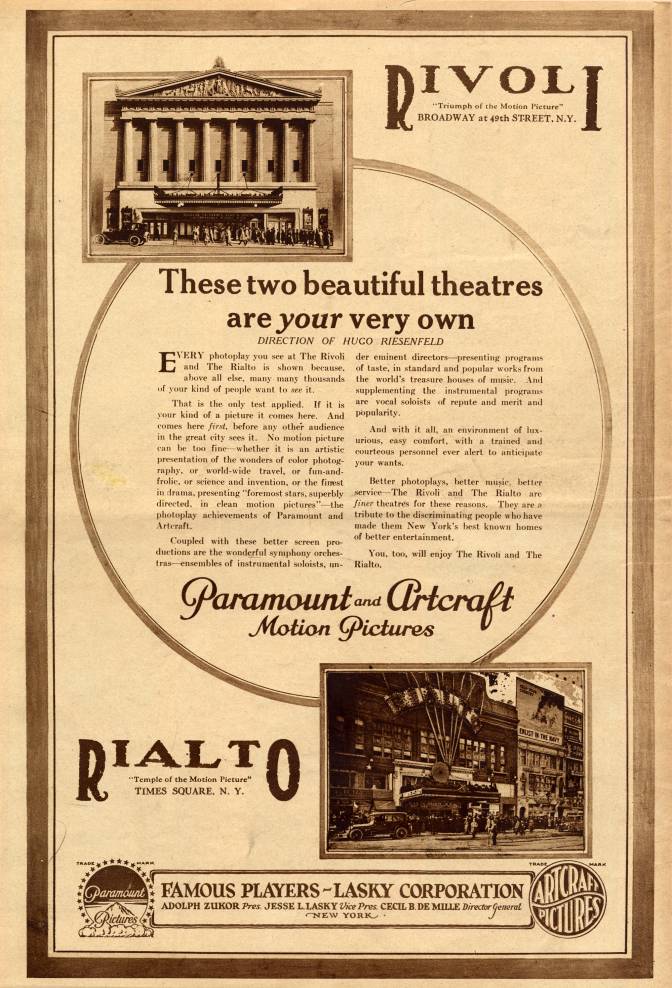

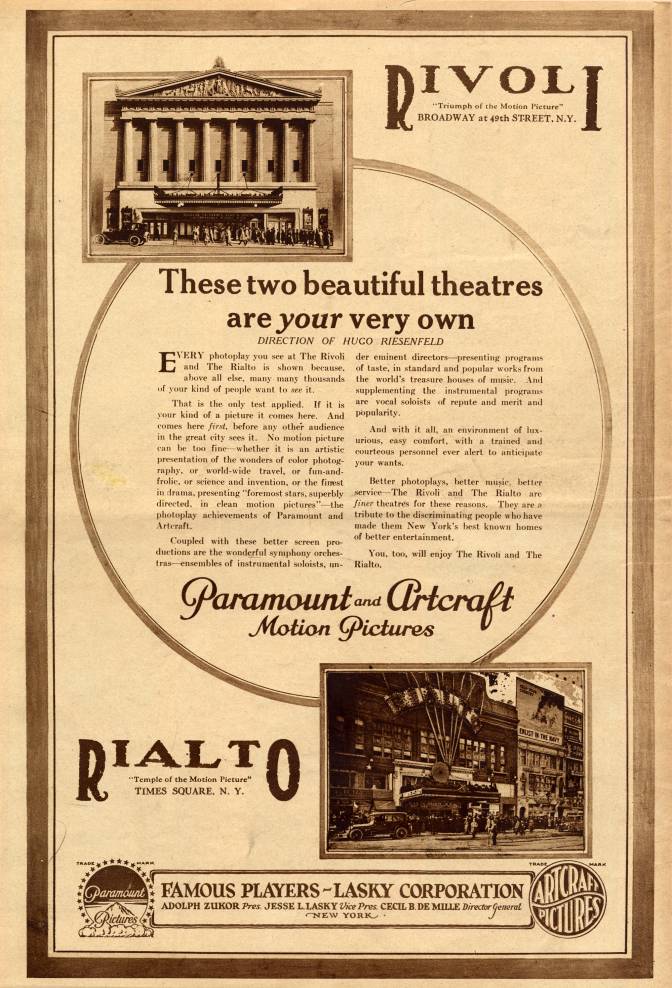

Old Ad shown for illustrative purposes

Old Ad shown for illustrative purposes The Rialto was built by Crawford Livingston and Felix Kahn, owners of the Mutual Film Company. Crawford Livingston (jr) ( 1848-1925 ), St.Paul, Minnesota Crawford Livingston was born in 1848, the same year his father died. He inherited a (relatively modest) share of the Livingston fortune and the genes which had made some of his forebears outstanding entrepreneurs. After an early career as a banker and broker in New York, Crawford Livingston headed West to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he became one of the foremost regional railroad developer and utility tycoon. By these means he built a large fortune and contributed to renew the Livingstons' claim to a position in the power elite. The town of Livingston, Montana is named in his honor. The Livingstons who played an important if not vital role in the inception of the key players in the express business, American Express and Wells, Fargo & Company, were all descendants of the mainline branch of Manor Lords. Crawford and William Alexander Livingston were brothers and among the initial investors in Livingston, Wells & Co and in Livingston, Fargo & Co, two of the three firms which joined to form American Express in March 1850. Their younger cousin, Johnston Livingston, joined them later but had the merit to stay in the express business for the rest of his life, more than sixty years. His career earned him the largest fortune of any Livingston descendent by the turn of the 20th century. Crawford Livingston later moved to New York and invested with his friend, Felix Kahn in the Rialto Theatre Corporation.

Rialto Theatre 1481 Broadway, NW corner of 42nd Street New York, N.Y. 10036 The Rialto Theatre, the original "Temple of the Motion Picture" and "The Shrine of Music and the Allied Arts", opened on April 21, 1916 on the site of the demolished Hammerstein's Victoria Theatre. The Rialto was built and first operated by Crawford Livingston and Felix Kahn, who hired S.L. "Roxy" Rothafel to be the managing director. Under Roxy's direction, the Rialto show ran five times daily and included the Rialto Orchestra, vocal and instrumental solos, and "accompaniment contributed by the grand organ". The success of the Rialto encouraged Livingston and Kahn to build the Rivoli, which opened in 1917, with "Roxy" Rothafel as managing director of both theatres. From 1919, the Rialto and Rivoli showed mostly Paramount releases, but that began to change in 1926, when the new Paramount Theatre opened and became the company's NYC "flagship." Paramount by that time also controlled the Criterion Theatre. There wasn't enough Paramount product for all four theatres, so the Rialto, Rivoli and Criterion began showing films from other distributors as well. With the advent of the Depression, Paramount could no longer afford to run four Broadway theatres, so the oldest of the group, the Criterion and Rialto, were sold and quickly demolished to make way for new buildings. In 1935, the Rialto was demolished and rebuilt on a smaller scale.

THE THEATRE MAGAZINE - 1916 The Rialto--A Theatre Without a Stage AN event of moment in the amusement life of New York was the opening, on April 22nd, of the Rialto Theatre at Fortysecond Street and Seventh Avenue, the former site of Hamnerstein's Victoria. A unique feature of this new cinema temple is that it has no stage. If the policy agreed upon is adhered to, as doubtless it will be, the popularity and the possibilities of motion pictures will be tested along lines that have been suggested, though never fully realized at the Strand, the one house at all comparable to the newest home of photographic art and music. The Rialto is a moderately large building, seating 2,000, quite enough to make the venture profitable if the chairs are occupied twelve hours out of every twenty-four; but exceptional capacity was not sought by the men who designed the theatre, whereas conspicuous decorations were studiously avoided. The aim of the management was not to advertise the greatest and most sumptuously appointed photoplay house in America. Sumptuous appointments are there, to be sure, but always unobtrusive. Following ideas that may appear hopelessly impracticable to the unimaginative exhibitor, Managing Director S. L. Kothapfel has realized his ideal of a building in which everything is subordinated to the display on the screen. Where the stage would ordinarily be located there is a permanent decoration in the form of a colonnade with marble stairs that- affords an effective location for soloists. Then the color scheme of the theatre is neutral. In the dome, old ivory is the prevailing tint, the decorations graduating into solid colors at the seating level, with reds predominant in the carpets, hangings and upholstery. Through this ingenious decorative treatment, in conjunction with a inarvelously intricate system of electric lighting, it is possible to vary the color tone in the auditorium that it may harmonize with the picture being shown, an unprecedented and, at least, creditable effort to place an audience in a receptive mood. The Rialto most certainly is the first theatre to offer an atmosphere so conducive to an appreciation of photoplays, and in another, probably more vital requisite, it is superbly equipped, liven as manager of the Regent, before he had achieved undisputed supremacy among exhibitors, Mr. Kothapfel perceived the natural connection between music and pictures, an alliance recently recognized by no less an authority than Hugo Munsterberg. A pretentious photoplay house without good music would be unthinkable in these days, so far have we advanced beyond the monotonous piano of unpleasant memory. Concealed behind the colonnade in the Rialto is the mechanism of a $60,000 organ, said to be the greatest ever installed in a theatre. Dr. Alfred G. Robyn and Edwin Johnson are the or- ganists who give daily recitals, alternating with the largest orchestra in New York, outside of the Metropolitan Opera House, under the direction of Hugo Riesenfeld. And supplementing the music furnished by organ and orchestra are concert soloists of the first rank. With such emphasis placed on this feature of the entertainment, it is not unreasonable to expect a clientele in part composed of music lovers, even if they do not chance to be devotees of screen entertainment. In devising exceptionally inviting surroundings and in offering superior music, the management of the Rialto has excelled; but it is the policy in selecting film subjects that marks a new, interesting and hopeful line in the progress of motion pictures. Much has been written about the educational possibilities of the screen, yet few exhibitors have risked the danger of becoming instructive at the expense of entertainment. T h e so-called feature photoplay is only a part of the program that offers much of significance to attentive audiences, largely because of the intelligent presentation of n e w s happenings, scientific subjects and other films calculated to stir thought. There is the "Rialto World-Wide News Service," designed to present a daily newspaper in film form, and also the "Rialto Pictorial Digest," which fills the same mission in the educational field, with editorials, travelogues, nature studies and cartoons. Felix Kahn, of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., and Crawford Livingston are largely interested in the Rialto Theatre Corporation . Mr. Rothapfel is vice-president and secretary, as well as managing director. Charles Stewart has been engaged to manage the house and Ben H. Atwell, director of publicity, is also editing the Rialto magazine.

The Rialto was built and first operated by Crawford Livingston and Felix Kahn, who hired "Roxy" Rothafel to be the managing director. The success of the Rialto encouraged Livingston and Kahn to build the Rivoli, which opened in 1917, with "Roxy" Rothafel as managing director of both theatres. Neither the Rialto nor the Rivoli were originated by the "Paramount" group of companies. In 1919, Famous Players-Lasky purchased the controlling interest in the Rialto and Rivoli as part of Adolph Zukor's plan to make the company more dominant in exhibition. From 1919, the Rialto and Rivoli showed mostly Paramount releases, but that began to change in 1926, when the new Paramount Theatre opened and became the company's NYC "flagship." Paramount by that time also controlled the Criterion Theatre. There wasn't enough Paramount product for all four theatres, so the Rialto, Rivoli and Criterion began showing films from other distributors as well. With the advent of the Depression, Paramount could no longer afford to run four Broadway theatres, so the oldest of the group, the Criterion and Rialto, were sold and quickly demolished to make way for new buildings. Paramount held on to the Paramount and Rivoli, but sold half of its interest in the Rivoli to United Artists Theatre Circuit, which also took over the management of the theatre. Many Paramount releases continued to open at the Rivoli until the end of WWII, when Paramount sold its half-interest to UATC, which by that time was part of 20th Century-Fox's theatrical interests.

In 1841 the firm of Pomeroy & Company was formed by George E. Pomeroy, Henry Wells and Crawford Livingston. In the express business they competed with the United States Post Office by carrying mail at less than the government rate. Popular support, roused by the example of the penny post in England, was on the side of the expressmen, and the government was compelled to reduce its rates in 1845 and again in 1851. Pomeroy & Company was succeeded in 1844 by Livingston, Wells & Company, composed of Crawford Livingston, Henry Wells, William Fargo and Thaddeus Pomeroy.[6] On April 1, 1845, Wells & Company's Western Express generally known simply as Western Express because it was the first such company west of Buffalo, New York was established by Wells, Fargo and Daniel Dunning.Service was offered at first as far as Detroit, rapidly expanding to Chicago, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. In 1846 Wells sold his interest in Western Express to William Livingston, whereupon the firm became Livingston, Fargo & Company. Wells then went to New York City to work for Livingston, Wells & Company, concentrating on the promising transatlantic express business. When Crawford Livingston died in 1847, another of his brothers entered the firm, which became Wells & Company. (However, Livingston, Wells & Company continued to operate under that firm name in England, France and Germany. The son and namesake of the first Livingston to invest in the express business, Crawford Livingston was born in 1848, the same year his father died. He inherited a (relatively modest) share of the Livingston fortune and the genes which had made some of his forebears outstanding entrepreneurs. After an early career as a banker and broker in New York, Crawford Livingston headed West to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he became one of the foremost regional railroad developer and utility tycoon. By these means he built a large fortune and contributed to renew the Livingstons' claim to a position in the power elite. The town of Livingston, Montana is named in his honor. The Livingstons who played an important if not vital role in the inception of the key players in the express business, American Express and Wells, Fargo & Company, were all descendants of the mainline branch of Manor Lords. Crawford and William Alexander Livingston were brothers and among the initial investors in Livingston, Wells & Co and in Livingston, Fargo & Co, two of the three firms which joined to form American Express in March 1850. Their younger cousin, Johnston Livingston, joined them later but had the merit to stay in the express business for the rest of his life, more than sixty years. His career earned him the largest fortune of any Livingston descendent by the turn of the 20th century. History from Wikipedia and OldCompany.com (old stock certificate research service)

Certificate

Old Picture shown for illustrative purposes

Old Ad shown for illustrative purposes

Old Ad shown for illustrative purposes

Rialto Theatre 1481 Broadway, NW corner of 42nd Street New York, N.Y. 10036 The Rialto Theatre, the original "Temple of the Motion Picture" and "The Shrine of Music and the Allied Arts", opened on April 21, 1916 on the site of the demolished Hammerstein's Victoria Theatre. The Rialto was built and first operated by Crawford Livingston and Felix Kahn, who hired S.L. "Roxy" Rothafel to be the managing director. Under Roxy's direction, the Rialto show ran five times daily and included the Rialto Orchestra, vocal and instrumental solos, and "accompaniment contributed by the grand organ". The success of the Rialto encouraged Livingston and Kahn to build the Rivoli, which opened in 1917, with "Roxy" Rothafel as managing director of both theatres. From 1919, the Rialto and Rivoli showed mostly Paramount releases, but that began to change in 1926, when the new Paramount Theatre opened and became the company's NYC "flagship." Paramount by that time also controlled the Criterion Theatre. There wasn't enough Paramount product for all four theatres, so the Rialto, Rivoli and Criterion began showing films from other distributors as well. With the advent of the Depression, Paramount could no longer afford to run four Broadway theatres, so the oldest of the group, the Criterion and Rialto, were sold and quickly demolished to make way for new buildings. In 1935, the Rialto was demolished and rebuilt on a smaller scale.

THE THEATRE MAGAZINE - 1916 The Rialto--A Theatre Without a Stage AN event of moment in the amusement life of New York was the opening, on April 22nd, of the Rialto Theatre at Fortysecond Street and Seventh Avenue, the former site of Hamnerstein's Victoria. A unique feature of this new cinema temple is that it has no stage. If the policy agreed upon is adhered to, as doubtless it will be, the popularity and the possibilities of motion pictures will be tested along lines that have been suggested, though never fully realized at the Strand, the one house at all comparable to the newest home of photographic art and music. The Rialto is a moderately large building, seating 2,000, quite enough to make the venture profitable if the chairs are occupied twelve hours out of every twenty-four; but exceptional capacity was not sought by the men who designed the theatre, whereas conspicuous decorations were studiously avoided. The aim of the management was not to advertise the greatest and most sumptuously appointed photoplay house in America. Sumptuous appointments are there, to be sure, but always unobtrusive. Following ideas that may appear hopelessly impracticable to the unimaginative exhibitor, Managing Director S. L. Kothapfel has realized his ideal of a building in which everything is subordinated to the display on the screen. Where the stage would ordinarily be located there is a permanent decoration in the form of a colonnade with marble stairs that- affords an effective location for soloists. Then the color scheme of the theatre is neutral. In the dome, old ivory is the prevailing tint, the decorations graduating into solid colors at the seating level, with reds predominant in the carpets, hangings and upholstery. Through this ingenious decorative treatment, in conjunction with a inarvelously intricate system of electric lighting, it is possible to vary the color tone in the auditorium that it may harmonize with the picture being shown, an unprecedented and, at least, creditable effort to place an audience in a receptive mood. The Rialto most certainly is the first theatre to offer an atmosphere so conducive to an appreciation of photoplays, and in another, probably more vital requisite, it is superbly equipped, liven as manager of the Regent, before he had achieved undisputed supremacy among exhibitors, Mr. Kothapfel perceived the natural connection between music and pictures, an alliance recently recognized by no less an authority than Hugo Munsterberg. A pretentious photoplay house without good music would be unthinkable in these days, so far have we advanced beyond the monotonous piano of unpleasant memory. Concealed behind the colonnade in the Rialto is the mechanism of a $60,000 organ, said to be the greatest ever installed in a theatre. Dr. Alfred G. Robyn and Edwin Johnson are the or- ganists who give daily recitals, alternating with the largest orchestra in New York, outside of the Metropolitan Opera House, under the direction of Hugo Riesenfeld. And supplementing the music furnished by organ and orchestra are concert soloists of the first rank. With such emphasis placed on this feature of the entertainment, it is not unreasonable to expect a clientele in part composed of music lovers, even if they do not chance to be devotees of screen entertainment. In devising exceptionally inviting surroundings and in offering superior music, the management of the Rialto has excelled; but it is the policy in selecting film subjects that marks a new, interesting and hopeful line in the progress of motion pictures. Much has been written about the educational possibilities of the screen, yet few exhibitors have risked the danger of becoming instructive at the expense of entertainment. T h e so-called feature photoplay is only a part of the program that offers much of significance to attentive audiences, largely because of the intelligent presentation of n e w s happenings, scientific subjects and other films calculated to stir thought. There is the "Rialto World-Wide News Service," designed to present a daily newspaper in film form, and also the "Rialto Pictorial Digest," which fills the same mission in the educational field, with editorials, travelogues, nature studies and cartoons. Felix Kahn, of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., and Crawford Livingston are largely interested in the Rialto Theatre Corporation . Mr. Rothapfel is vice-president and secretary, as well as managing director. Charles Stewart has been engaged to manage the house and Ben H. Atwell, director of publicity, is also editing the Rialto magazine.

The Rialto was built and first operated by Crawford Livingston and Felix Kahn, who hired "Roxy" Rothafel to be the managing director. The success of the Rialto encouraged Livingston and Kahn to build the Rivoli, which opened in 1917, with "Roxy" Rothafel as managing director of both theatres. Neither the Rialto nor the Rivoli were originated by the "Paramount" group of companies. In 1919, Famous Players-Lasky purchased the controlling interest in the Rialto and Rivoli as part of Adolph Zukor's plan to make the company more dominant in exhibition. From 1919, the Rialto and Rivoli showed mostly Paramount releases, but that began to change in 1926, when the new Paramount Theatre opened and became the company's NYC "flagship." Paramount by that time also controlled the Criterion Theatre. There wasn't enough Paramount product for all four theatres, so the Rialto, Rivoli and Criterion began showing films from other distributors as well. With the advent of the Depression, Paramount could no longer afford to run four Broadway theatres, so the oldest of the group, the Criterion and Rialto, were sold and quickly demolished to make way for new buildings. Paramount held on to the Paramount and Rivoli, but sold half of its interest in the Rivoli to United Artists Theatre Circuit, which also took over the management of the theatre. Many Paramount releases continued to open at the Rivoli until the end of WWII, when Paramount sold its half-interest to UATC, which by that time was part of 20th Century-Fox's theatrical interests.

In 1841 the firm of Pomeroy & Company was formed by George E. Pomeroy, Henry Wells and Crawford Livingston. In the express business they competed with the United States Post Office by carrying mail at less than the government rate. Popular support, roused by the example of the penny post in England, was on the side of the expressmen, and the government was compelled to reduce its rates in 1845 and again in 1851. Pomeroy & Company was succeeded in 1844 by Livingston, Wells & Company, composed of Crawford Livingston, Henry Wells, William Fargo and Thaddeus Pomeroy.[6] On April 1, 1845, Wells & Company's Western Express generally known simply as Western Express because it was the first such company west of Buffalo, New York was established by Wells, Fargo and Daniel Dunning.Service was offered at first as far as Detroit, rapidly expanding to Chicago, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. In 1846 Wells sold his interest in Western Express to William Livingston, whereupon the firm became Livingston, Fargo & Company. Wells then went to New York City to work for Livingston, Wells & Company, concentrating on the promising transatlantic express business. When Crawford Livingston died in 1847, another of his brothers entered the firm, which became Wells & Company. (However, Livingston, Wells & Company continued to operate under that firm name in England, France and Germany. The son and namesake of the first Livingston to invest in the express business, Crawford Livingston was born in 1848, the same year his father died. He inherited a (relatively modest) share of the Livingston fortune and the genes which had made some of his forebears outstanding entrepreneurs. After an early career as a banker and broker in New York, Crawford Livingston headed West to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he became one of the foremost regional railroad developer and utility tycoon. By these means he built a large fortune and contributed to renew the Livingstons' claim to a position in the power elite. The town of Livingston, Montana is named in his honor. The Livingstons who played an important if not vital role in the inception of the key players in the express business, American Express and Wells, Fargo & Company, were all descendants of the mainline branch of Manor Lords. Crawford and William Alexander Livingston were brothers and among the initial investors in Livingston, Wells & Co and in Livingston, Fargo & Co, two of the three firms which joined to form American Express in March 1850. Their younger cousin, Johnston Livingston, joined them later but had the merit to stay in the express business for the rest of his life, more than sixty years. His career earned him the largest fortune of any Livingston descendent by the turn of the 20th century. History from Wikipedia and OldCompany.com (old stock certificate research service)