Beautiful certificate from the Vanderbilt Hotel Corporation issued in 1929. This historic document was printed by American Banknote Company and has an ornate border around it with a vignette of the original Vanderbilt Hotel. This item has the signatures of the Company's Vice-President and Secretary and is over 79 years old. The certificate was issued to Charles D. Wetmore of Warren & Wetmore (designers of Grand Central Terminal and Vanderbilt Hotel Corporation ). This is the first time we have had this certificate for sale.

Certificate Vignette The Vanderbilt Hotel, 34th Street and Park Avenue Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, the great-grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, the railroad magnate, built the hotel in 1912. Heir to millions, Alfred Vanderbilt had grown up in the palatial family house at 57th Street and Fifth Avenue, where Bergdorf-Goodman now stands. He built his new hotel primarily for permanent residents, to accommodate a new generation of the rich who sought freedom from household cares -- including himself. He took two floors at the top of the 22-story building. The architects Warren & Wetmore (co-designers of Grand Central Terminal, also build for the Vanderbilt family) designed one of the most widely admired buildings of the period, a slim, high rectangular mass of variegated steel-gray brick and cream-colored terra cotta. The building was in fact a showcase for terra cotta. The ground floor boasted huge Adam-style windows with delicate fluted fans; the upper portions had a rich, frothy network of terra-cotta colonettes, helmets, lions' heads and lozenge shapes, all set against a crisscross brick pattern. The roof omitted the usual projecting cornice (by then criticized for casting shadows) for a parapet festooned with lacy decoration with classical heads. To add a whimsical touch, the curving parapet at the top was outlined in electric lights. A critic for the magazine Architecture & Building loved the gray brick for its complex undercurrent of ''hidden and indescribable golden browns and blues,'' calling it ''a sight worth crossing a continent to see.'' Susan Tunick, head of the Friends of Terra Cotta, says that the material was the work of the New Jersey Terra Cotta Company. The emphasis on permanent residents in the Vanderbilt freed Warren & Wetmore from the usual constraints of hotel design. Since the hotel did not require a large ballroom, the architects were able to make the first floor one huge lounge, with high vaulted ceilings. A portion of the ground floor was set up as a dining room, but the much larger grill room and bar -- several fantastical arched spaces covered in polychrome terra cotta -- were on the basement floor. An unidentified assistant manager told The New York Times that the hotel's public spaces could be more homelike than usual, adding that ''it has been our aim in decorating the house to eliminate the red and gold idea in hotel decoration.'' Instead of the usual heavy velvet and gilt ornament, the interiors used a chaste mix of simple stone surfaces with carved stone friezes on the upper walls. Amenities like pneumatic tubes that could deliver messages from bottom to top in seven seconds led the magazine American Architect to praise the Vanderbilt as ''a memory of the land of ancient courtesies'' in an increasingly hectic age. Some idea of the character of the Vanderbilt's guests is given in a 1913 account in The Times. An unidentified family left the hotel unexpectedly, and their French maid, identified only as Felice, hurriedly packed the trunk dedicated to her mistress's furs. In her rush, the maid closed the lid on the family dog, a tiny Pomeranian named Papillon. The dog was found only when the hotel's elevator operator became alarmed by moaning from the trunk. THE 1915 census included residents like Duncan Roberts, 62, president of the United States Express Company, a parcel-delivery concern. The census, recorded in June, did not list Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt. He had died a hero in May after giving his life jacket to a woman on the Lusitania, which sank after being torpedoed by the Germans off Ireland. Vanderbilt's apartment was taken over by the Women's City Club, whose literary and politically active members came to hear guests like George Kirchwey, warden of Sing Sing prison, lecture on social issues. The renowned tenor Enrico Caruso later took the suite. On. Jan. 1, 1921, ill with pleurisy, he was attended by six physicians, who were especially concerned that the noise from New Year's revelers was keeping him awake, even though they were far below. Caruso died in Naples that August. The Vanderbilt heirs sold the building in 1925. In 1967, the hotel was converted to apartments on the upper floors, with offices on the lower six. The bar adjacent to the terra cotta grill complex survived fairly intact and is now the restaurant Vanderbilt Station. At the time, one plan was to strip the building to its steel frame. But only the lower floors were modernized, by the architects Schuman, Lichtenstein & Claman. The lower facade was stripped away, replaced with a modern facade of travertine.

Warren and Wetmore was an architecture firm in New York City. It was a partnership between Whitney Warren (18641943) and Charles Wetmore (18661941), that had one of the most extensive practices of its time and was known for the designing of large hotels. Whitney Warren was a cousin of the Vanderbilts and spent ten years at the Ãcole des Beaux Arts. There he met fellow architecture student Emmanuel Louis Masqueray, who would, in 1897, join the Warren and Wetmore firm. He began practice in New York City in 1894. Warren's partner, Charles D. Wetmore, was a lawyer by training. Their society connections led to commissions for clubs, private estates, hotels and terminal buildings, including the New York Central office building, the Chelsea docks, the Ritz-Carlton, Biltmore, Commodore, and Ambassador Hotels. They were the preferred architects for Vanderbilt's New York Central Railroad. The firm's most important work by far is the Grand Central Terminal in New York City, completed in 1913 in association with Reed and Stern. Warren and Wetmore were involved in a number of related hotels in the surrounding "Terminal City". Whitney Warren retired in 1931 but occasionally served as consultant. Warren took particular pride in his design of the reconstructed library at the Catholic University of Leuven, finished in 1928, which carried the controversial inscription Furore Teutonico Diruta: Dono Americano Restituta ("Destroyed by German fury, restored by American generosity") on the facade. The library was largely destroyed by German forces again in 1940. The architectural records of the firm are held by the Dept. of Drawings & Archives at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University. History from the New York Times and Wikipedia.

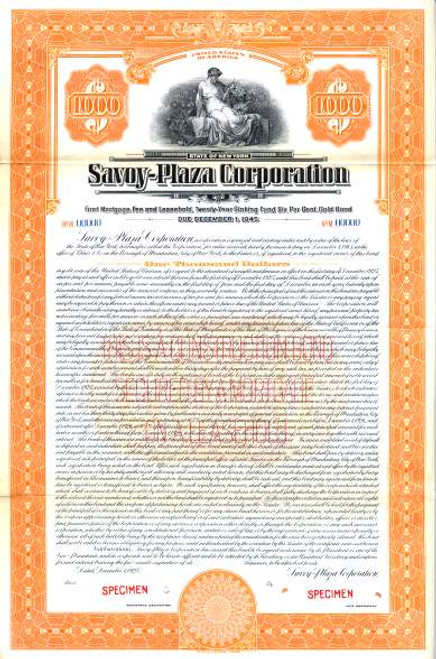

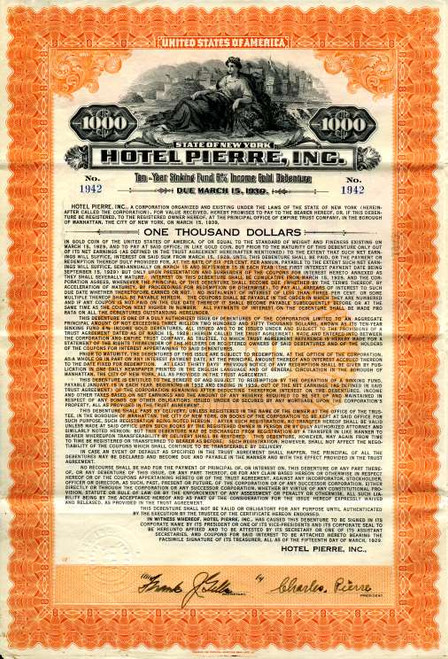

Certificate Vignette

Warren and Wetmore was an architecture firm in New York City. It was a partnership between Whitney Warren (18641943) and Charles Wetmore (18661941), that had one of the most extensive practices of its time and was known for the designing of large hotels. Whitney Warren was a cousin of the Vanderbilts and spent ten years at the Ãcole des Beaux Arts. There he met fellow architecture student Emmanuel Louis Masqueray, who would, in 1897, join the Warren and Wetmore firm. He began practice in New York City in 1894. Warren's partner, Charles D. Wetmore, was a lawyer by training. Their society connections led to commissions for clubs, private estates, hotels and terminal buildings, including the New York Central office building, the Chelsea docks, the Ritz-Carlton, Biltmore, Commodore, and Ambassador Hotels. They were the preferred architects for Vanderbilt's New York Central Railroad. The firm's most important work by far is the Grand Central Terminal in New York City, completed in 1913 in association with Reed and Stern. Warren and Wetmore were involved in a number of related hotels in the surrounding "Terminal City". Whitney Warren retired in 1931 but occasionally served as consultant. Warren took particular pride in his design of the reconstructed library at the Catholic University of Leuven, finished in 1928, which carried the controversial inscription Furore Teutonico Diruta: Dono Americano Restituta ("Destroyed by German fury, restored by American generosity") on the facade. The library was largely destroyed by German forces again in 1940. The architectural records of the firm are held by the Dept. of Drawings & Archives at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University. History from the New York Times and Wikipedia.