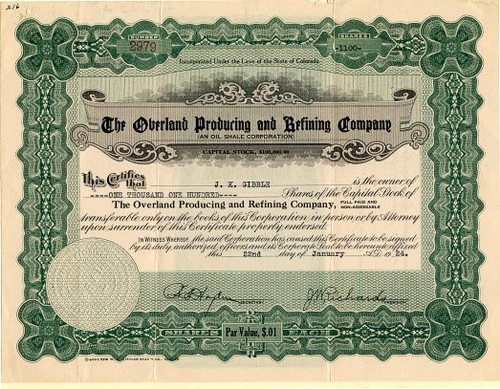

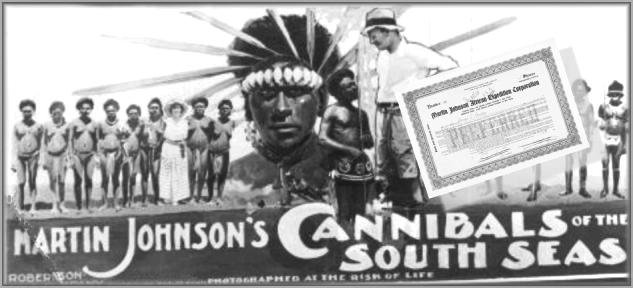

Unique and beautifully printed scare Certificate from the Martin Johnson African Expedition Corporation issued no later than 1926. This historic document has an ornate border around it with an imprint of the corporate seal and a back print of the word Preferred to represent the class of stock that was issued. This item is hand signed by the company's president, Daniel E. Pomeroy and is over 98 years old.

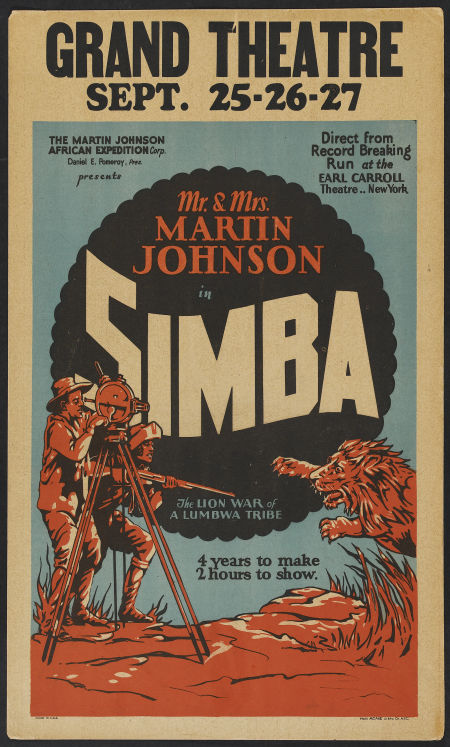

Old Martin Johnson Movie Poster, from the movie "Simba" shown for illustrative purposes

The Martin Johnson African Expedition Corporation was the production company for the movie, "Simba, the King of Beasts" which was released in 1928. Produced by Daniel Eleazer Pomeroy, famed financier, director Bankers Trust Co., Loew's, Inc., Daniel Pomeroy Daniel E. Pomeroy was best man for Henry P. Davison when he married Kate Trubee. (Some April Weddings. Apr. 14, 1893.) His father was Newton Merrick Pomeroy of Troy, Pennsylvania, who was also an uncle of H.P. Davison. (Obituary Notes. New York Times, Feb. 19, 1914; Mr. N.M. Pomeroy Succombs to Pneumonia. Troy Gazette-Register, Feb. 20, 1914.) He was a director of Loew's Inc. (Schenck Succeeds to Loew's Posts. New York Times, Sep. 27, 1927.) He was a close friend of Jay Cooke, grandson of the Civil War financier, and accompanied Cooke's body home from England. (Jay Cooke is Dead; Friend of Hoover. New York Times, Nov. 23, 1932.) He resigned as a vice president of the Bankers Trust in 1922. He married Frances Morse of Troy in 1895. After she died, he married Mrs. Trevania Blair-Smith, the widow of Hugh Blair-Smith, treasurer of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company. (Mrs. Blair-Smith Engaged to Wed. New York Times, Jan. 2, 1937; Pomeroy-Blair-Smith. New York Times, Feb. 5, 1937.) He was born in 1868 in Troy, Penn., and after graduating from the Greylock Institute, went to work in the Pomeroy family bank. He came to the Bankers Trust as treasurer in 1903 at the request of "a cousin," and continued as a director of the Bankers Trust until his death. He was also a director of the American Brake Shoe Company and the Bucyrus Erie Company. He was the Eastern campaign manager for Herbert Hoover in 1928, and was a member of the Republican National Committee until 1942. (Daniel Pomeroy, Banker, 96, Dies. New York Times, Mar. 26, 1965.)

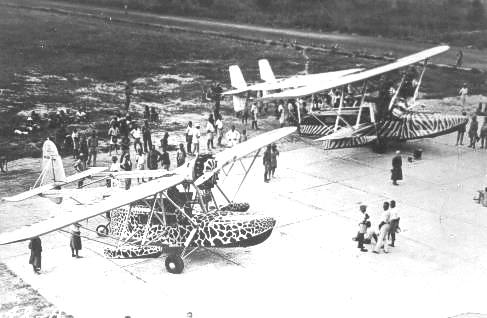

Photographers, explorers, naturalists, authors, and native Kansans, Martin and Osa Johnson traveled the world from 1917-1936. The Johnsons are best remembered for their numerous movies and books about the wildlife and people of Africa, Borneo, and the South Seas. They popularized camera safaris and introduced Americans to a larger world. In the 1930s, Kansas husband-and-wife team Osa and Martin Johnson, flying two Sikorsky amphibian aircraft painted in animal motifs, covered 60,000 miles and photographed the land and peoples of Africa. The Johnsons introduced Depression-era audiences to the beauty of East Africa with their popular travel books and safari documentary films like Baboona. They circled the world six times, bringing their experiences to the screen for all to see. Their most famous film CONGORILLA (for which project this certificate was presumably issued to fund), took two years to make and required the husband and wife team to live with pygmies for seven months. Their achievements are preserved by the Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum in Osa's hometown of Chanute, Kansas.

by Conrad G. Froehlich "If you want to know something essential about adventurers Osa and Martin Johnson, look at their photographs. Startled giraffes lumbering across a treeless plain. A lion standing motionless and serene in tall grasses. A mother cuddling her child. The pictures are rich and insightful, images that are at once foreign and familiar. Shot 60 and 70 years ago by a Kansas couple documenting remote and exotic scenes, the photos...evoke universal themes and human values." --Mary Lou Nolan, Travel Editor, Kansas City Star

People remember Martin and Osa Johnson most for their movies of Africa, Borneo, and the South Seas. Although this work may represent an outmoded genre of travel-adventure films, the Johnsons' legacy--remaining in thousands of photographs, hundreds of cans of motion picture film footage, and numerous books and articles--remains an invaluable contribution to our knowledge of some of the world's most beautiful, and mysterious, places.

Martin Johnson described himself as a "Motion Picture Explorer." With his wife Osa, a pioneer photographer/filmmaker in her own right, they exposed about one million feet of film. These days, the Johnson's achievements are once again in the limelight, thanks in good part to the 1997 republication of Osa Johnson's 1940 bestseller I Married Adventure, the printing of a comprehensive Johnson biography entitled They Married Adventure: The Wandering Lives of Martin & Osa Johnson (1992), and the release of the film Simba (1928) on video and laserdisc.

Much has changed since the Johnsons' heyday in the first half of the century, but the wildlife and cultures they captured on film are frozen in time. Despite their primitive equipment and initial inexperience, their films and photos continue to be of great value to filmmakers, historians, botanists, zoologists, and anthropologists. By current standards, the Johnsons' films are technically inferior to the nature shows we watch on television. Today, improved sound equipment and cameras with zoom and telephoto lenses make filming wildlife much easier and safer. With that in mind, it is easier to appreciate the mastery and difficulty of the Johnson's work. Martin Johnson's ability to photograph and develop his own film in the field made him a master at working in primitive conditions.

The word "closeup" for the Johnsons was certainly an accurate description. To get close enough to take clear shots of their subjects, they often found themselves in dangerous situations when approaching wild animals on foot or by open car. This sometimes meant getting as close as eight feet from an elephant, or 12 feet from a rhino. Also, in their day, chance encounters with large animals occurred more frequently: Wildlife populations were far more robust then, and human populations smaller. Martin tried to distance himself from other pioneer photographers and explorers of the time, such as Frank Buck, who mostly filmed captive animals and fight sequences using various improbable antagonists. Martin wrote in his book Camera Trails in Africa (1924): "Films of remote countries, primitive people, and wild animals are usually little more than moving-picture-books. They show a series of scenes, for the most part unrelated and assembled with an eye to pleasing the commercial producer. The titles are usually sensational or inaccurate or both. The pictures themselves are often "staged" for the camera and are no more representative of the actual lives of the savage men or wild animals than they would be if taken in Hollywood. I want to take a picture of Africa that will be different. It will be the whole story of a country, its people, and its animals, slowly unrolling against a background of magnificent scenery--wide grassy plains dotted with sparse mimosa groves, peaceful wooded hills, rugged, barren mountain ranges, rich forests, desolate lava fields, swift rivers, broad sandy beaches...it will show the animals, not hunted and afraid, but natural and unaware, untroubled by man." Investors supported the Johnson's early expeditions. But as their fame grew, Martin and Osa largely funded their later trips through corporate sponsors and proceeds from their lectures, movies, books, and articles. Martin liked to say they invested in themselves. The Kansas Connection The Johnson story begins far from the exotic tropics, in Kansas. Although born in Rockford, Illinois, in 1884, Martin spent his youth in the Kansas communities of Lincoln and Independence. His father, John Johnson, operated a combination book store and jewelry shop. Papa Johnson's dream of his son taking over the business was never realized, due in part to his purchase of an Eastman-Kodak franchise. Photography sparked the young Johnson's imagination, and with access to cameras, photographic supplies, and a darkroom, he became a roving photographer, taking penny pictures in southeast Kansas. Martin's life took a dramatic turn in 1906. By this time, he had already caught the travel bug, having journeyed through the United States and Europe. When Martin found out that famed travelers and authors Jack and Charmian London (then aged 30 and 35, respectively) were building a ship to sail around the world, he wrote them an enthusiastic six-page letter. They responded by inviting Martin to join them as a cook. Martin's culinary skills left something to be desired, but the young man's photographic talents were not lost on the Londons. From 1907 to 1909, Martin sailed on the Snark, which the Londons had named after the Lewis Carroll poem. Later in 1909, Jack London returned to the United States a very sick man, plagued by bouts of malaria, intestinal fistula, skin ulcers, and nutritional deficiencies. This ended the "around the world" trip in the South Seas. Martin returned to Independence, Kansas, with pictures, film, objects, and stories--props that soon became vital tools used in Martin's newly launched career as a travelogue lecturer. On his first tour, his programs rotated through five southeast Kansas towns from 1909 to 1910. Osa and the South Seas Born in Chanute, Kansas, in 1894, Osa Leighty led an ordinary settled life until she met Martin Johnson. She learned domestic skills from her mother and grandmother. Her father taught her to hunt, fish, and garden. And her aunt, Minnie Thomas, a cigar-smoking circus bareback rider, provided inspiration for the aspiring performer. Osa too entertained crowds, though she channeled her energy into more musical pursuits. An indifferent student, she far preferred singing and dancing at school functions to doing homework. Martin and Osa were introduced by Osa's best friend Gail Perigo in 1910. Gail, who worked with Martin, recommended an arranged meeting between the two. Despite disliking Martin's lectures, Osa agreed to the meeting. They were instantly attracted to each other. For Osa, Martin represented an acclaimed world traveler with similar Midwest values and manners. To Martin, Osa was attractive, charming, and adventuresome, with solid values--all he wanted in a wife. On May 15, about a month after meeting, they eloped and began a long journey together. From 1910 to 1917, the Johnsons traveled the United States and Canada, presenting their lecture program "Martin E. Johnson's Travelogues," among other titles. They also spent several seasons on the vaudeville Orpheum Circuit, sharing bills with Will Rogers, W.C. Fields, and other notable vaudevillians of the time. While this work did not bring the Johnsons wide recognition, it helped them better understand the entertainment business and secure important contacts for backing their proposed travel and filming plans. In 1917, Martin and Osa departed on a South Seas adventure. With the help of friends, they had raised enough money to finance a nine-month trip through the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) and Solomon Islands. The highlight of the trip was a brief, but harrowing, encounter with a tribe called the Big Nambas of northern Malekula. Martin's determination to film their powerful chief Nihapat overrode caution and the Johnsons allowed themselves to be led into the hill forests of the island. Once the Johnsons met Nihapat, the Big Nambas barred them from leaving. To this day, no one knows if the tribe meant the Johnsons any harm. Nonetheless, the timely arrival of a British gunboat in a bay near the forest allowed them to escape with some exceptional footage and a great story of capture by "cannibals." This adventure inspired the feature film Cannibals of the South Seas (1918). The Johnsons returned to Malekula in 1919 to film the Big Nambas once again. However, this time they brought along 26 armed Melanesians. But what really disarmed the Big Nambas was watching themselves in Cannibals of the South Seas, a rather dramatic event that the Johnsons also filmed. This interaction was apparently the first time ethnographic filmmakers shared their work with their subjects and received their comments. Such screenings are common practice today. Martin and Osa capped off their trip in 1920 with visits to British North Borneo (now Sabah) and a sailing expedition up the coast of East Africa. After returning home, they released the features Jungle Adventures (1921) and Headhunters of the South Seas (1922). On to Africa Through their friendship with famous naturalist Carl Akeley, the Johnsons embarked on the African safaris for which they are best remembered. They developed a deep love for the land, people, and animals of East Africa, and worked hard to produce work that would convey their passion to their audiences. They soon became household names in America and enjoyed fame worldwide, their films and books translated into numerous languages. Although products of their times--prone to using words like "savage" to describe a native islander and as likely to carry a gun as a camera--the Johnsons were progressive in their outlook on the animals they stalked. Many consider them among the earliest protectors of African wildlife, and claim they were instrumental in debunking the stereotype of Africa as the "Dark Continent." They brought back images of a tranquil, beautiful land and inspired many to visit Africa. As Mark C. Reed, director of the Sedgwick County Zoo in Wichita, Kansas, puts it, "...they were among the first to lay the foundation for all the interest we have now in conservation of animals and nature." The Johnson's first Africa expedition, from 1921 to 1922, resulted in their feature film Trailing Wild African Animals (1923). The second and longest trip, from 1924 to 1927, was partially supported by the American Museum of Natural History. During this trip the Johnsons spent much of their time in northern Kenya at their home by a lake they dubbed Paradise, at Mount Marsabit. This provided them the opportunity to film migrating animals in a variety of situations. In January 1927, they attempted to climb Mount Kenya. After reaching 12,000 feet, the Johnsons and several others developed high fevers and had to be carried off the mountain. Osa, who fell unconscious, spent six weeks recovering from pneumonia and high-altitude illness. This period is covered in Martin's Safari (1928) and Osa's Four Years in Paradise (1941), and in their film Simba (1928). A trip up the Nile with friend and supporter George Eastman (of Eastman-Kodak fame) highlighted the third African safari, from 1927 to 1928. One of the results of this trip was a hybrid film typical of the transition period between silent and sound movies. Across the World with Mr. and Mrs. Johnson (1930) included footage from all of their travels, bound together by Martin's narrative. From 1929 to 1931, the Johnsons spent a fourth tour in Africa. This time they ventured into the then Belgian Congo to film the Mbuti people of the Ituri Forest and the gorillas in the Alumbongo Hills. The 1932 feature movie Congorilla was in part a product of this trip, and was the first movie with sound authentically recorded in Africa. While backing from the Fox Film Corporation provided financial support, and the film was released by Fox, Martin complained of studio interference. Current critics of the Johnsons' work often ignore this pressure, which led to some staged scenes and racial slurs sadly common in this period. On their fifth African trip, from 1933 to 1934, the Johnsons took two Sikorsky amphibious planes, named "Osa's Ark" and "The Spirit of Africa," and flew the length of Africa. The planes, which could operate on both land and water, provided an easier and faster means of reaching wilderness areas than traveling by car or boat. The Johnsons became the first to fly over the peak of Mount Kenya and film it from the air. The 1935 feature film was also underwritten by the Fox Film Corporation and carried the Hollywood sounding title Baboona. Arguably the Johnsons' most recognized and best movie, Baboona includes now classic aerial scenes of large herds of elephants, giraffes, and other animals moving across the plains of Africa. End of an Era The Johnsons' final trip together took them to British North Borneo again, from 1935 to 1936. They used their smaller amphibious plane, now renamed "The Spirit of Africa and Borneo," and produced footage for the feature Borneo (1937). In 1937, the Johnsons began a lecture tour across the United States with their Borneo footage. While traveling from Salt Lake City to Burbank, their Western Air Express Boeing 247 strayed off course and crashed in bad weather. Martin died the following day, January 13, 1937, from his injuries and from complications of his untreated diabetes. While still in a wheelchair with knee and back injuries, Osa completed the interrupted lecture circuit. She returned to Kenya later that year to act as a technical consultant for the filming of the classic movie Stanley and Livingstone (1939). Following Martin's death, Osa did most of her writing, including I Married Adventure (1940, republished in 1989 and 1997) and Bride in the Solomons (1944). Osa also made various silent lecture films, such as African Paradise (1941), which she took around the country and narrated. She also supplied narration and footage for the 1950s television series Osa Johnson's Big Game Hunt. The success of I Married Adventure resulted in a Columbia Pictures feature by the same name in 1940. Studio shots with Osa playing herself and a less-than-convincing stand-in for Martin were used with actual Johnson footage to tell their story. The movie was popular, despite the panning it received from critics. After 1937, Osa never returned to Africa. She was briefly married to manager/agent Clark Getts, but she could not find another Martin. Without Martin's influence, alcoholism took a toll on her career and health. In the years that followed, she did lecture and appear on television, but her work mostly reflected her and Martin's earlier years. On January 7, 1953, Osa died of a heart attack. Because the Johnsons' films and photographs represent some of the earliest and best quality images of our natural world, they continue to be used in documentary programs in the U.S. and abroad. It is remarkable that their work continues to educate people about wildlife conservation issues--more than a half-century after their travels. According to Bill Toone, director of conservation at the San Diego Zoo, "They inspired literally generations of zoo biologists and the pictures and films that the Johnsons left behind are a picture of a world that we don't have an opportunity to go out and see anymore." Author Conrad G. Froehlich earned an M.A. in Anthropology from Miami University (Oxford, Ohio), and has been the director of the Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum since 1989. A LASTING LEGACY A number of large U.S. institutions maintain significant Johnson archives, including the Library of Congress, the American Museum of Natural History, the Museum of Modern Art, the International Museum of Photography (George Eastman House), the American Heritage Center (University of Wyoming), and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. However, the Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum, in Osa's hometown of Chanute, Kansas, is the only museum primarily dedicated to the lives and work of this intrepid couple. Within the museum's collection are about 10,000 Johnson photographs. In addition to the world's largest Johnson archive, the museum also houses the Imperato African Gallery, Selsor Art Gallery, Henshall Archives, and Stott Explorers Library, which includes 10,000 volumes of natural history and exploration subjects. For more information, contact the Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum at 111 N. Lincoln Avenue, Chanute, Kansas 66720, or call 316.431.2730. OSA JOHNSON CAPTURES ADVENTURES FOR KANSAS HISTORY Osa Leighty was unimpressed by the young photographer who took her brother's portrait. She was more concerned that her three-year-old brother sit still. It was hot, and she wanted to get home. The photographer, Martin Johnson, had traveled from Independence to Chanute to sell photographs at a penny a piece. The chance meeting marked the beginning of an adventurous partnership that made Kansas history. Martin Johnson spent the next several years traveling with Jack London and taking photographs in exotic places in the South Pacific. When he returned to Kansas in 1910 he traveled to Chanute to lecture and show his slides at an evening performance. The girl who was hired to provide musical entertainment for that performance was a friend of Osa's, and arranged a formal introduction between the two. Osa was still not impressed. Martin was conceited and his photos of cannibals were horrible. Nonetheless, sixteen-year-old Osa was drawn to Martin, ten years her senior. They dated for three weeks and got married on a whim. To avoid having the marriage annulled by her father, Martin and Osa traveled to Kansas City, Missouri, for a second wedding. During the twenty-seven years they were married, Osa and Martin traveled around the world photographing wild animals and native peoples in the South Sea islands, Borneo, and Africa. Martin stayed behind the camera while Osa kept watch. Once, as Martin was photographing a herd of rhinoceroses, one of the animals caught wind of them and charged directly at Martin. With her trademark calmness, Osa raised her rifle, shot, and killed the charging rhino. Martin never missed a second of the action, capturing the dramatic moment on film. Osa coordinated their trips, arranging for transportation of thousands of dollars of photographic equipment and supplies. On one African safari, Osa supervised the 235 porters who carried their supplies over swamplands where vehicles could not go. Following each trip, Osa and Martin would return to the United States to lecture showing their movies and telling of their travels.

The Johnsons prided themselves on the natural accuracy of their movies. Rarely was the action staged and usually it was unpredictable. Osa and Martin never had children, but Osa was rarely seen without one of her pet monkeys riding on her shoulder. Osa recorded her life story in the book I Married Adventure. Osa was a pioneer who insisted that she stand as Martin's equal. In 1932 the Johnsons learned to fly at the airfield in Osa's hometown of Chanute. With pilot's licenses in hand, they purchased two airplanes and set off for Africa. Piloting Osa's Ark, Osa flew over the savannas of Africa to photograph the wildlife from the air. They were the first pilots to fly over Mt. Kilimanjaro and Mt. Kenya in Africa. Later, they took their aircraft to Borneo and flew over the interior of the island photographing wildlife and native peoples. Together, Osa and Martin made eight feature movies, shot thousands of photographs, published nine books, and traveled thousands of miles presenting lectures and showing their films. In 1937, following a two-year trip to Borneo, the Johnsons were once more lecturing around the U.S. Traveling from Salt Lake City to California, the commercial plane on which they were traveling crashed during a thunderstorm. Martin died from his injuries. Osa, though badly injured, continued their planned tour lecturing from a wheelchair. Following Martin's death, Osa continued lecturing, writing, and producing motion pictures. Osa was planning a return visit to East Africa when she suffered a heart attack and died in New York City in 1953. Osa and Martin are buried in Chanute. The Martin and Osa Johnson SAFARI Museum in Chanute now holds many of their photographs and personal memorabilia.

History from RM Smythe.